|

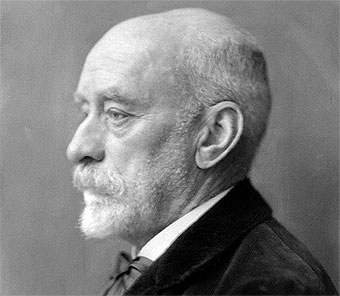

| HENDRIK PETRUS BERLAGE |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Name |

|

Hendrik Petrus Berlage |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Born |

|

February 21, 1856 |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Died |

|

August 12, 1934 |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Nationality |

|

Netherlands |

| |

|

|

|

| |

School |

|

AMSTERDAM SCHOOL; ART NOUVEAU |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Official website |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| BIOGRAPHY |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Hendrik Petrus Berlage was one of the most significant European architects before World War I. Often considered the father of modern architecture in the Netherlands, Berlage greatly influenced a generation of architects that included J.J.P.Oud, Gerrit Rietveld, and Mies van der Rohe. His work is known for its transition from 19th-century historicism to new styles and theories of modern architecture. While his early designs were revivalist Dutch Renaissance, in the 1890s Berlage rejected historicism to experiment instead with stylistically innovative forms. Often considered a rationalist, Berlage was similarly noted for his restrained use of ornament and his insistence that the exterior of a building express its interior, functional design. Berlage was a pioneer in the development of 20th-century architecture, and many of his buildings are Dutch cultural landmarks.

Berlage’s career falls into three periods: 1878 to 1903, his early work through the completion of the Amsterdam Exchange; 1903 to 1919, his mature period through the termination of his work for the Kröller-Müller family; and his late work from 1920 to 1934, when he turns to Cubist forms. Berlage received his formal architectural training at the Zürich Polytechnic. After extensive travels, he began working in the Amsterdam office of Theo Sanders. When Sanders retired in 1889, Berlage opened an independent office. His first major commission was the purely historicist De Algemeene office building in Amsterdam. His experiments with restrained, stylized historical forms culminated in the Amsterdam Exchange. The five successive Exchange designs (1884– 98) show Berlage’s transformation from historicism to modernism. Beginning as a Dutch Renaissance palace, the Exchange became an original design, reinterpreting, abstracting, and subjecting historical forms to new ideas about proportion and materials. The Exchange uses a proportional grid of triangular prisms that harmonizes and unifies the exterior. In conception, it drew on history as well, as Berlage sought to adapt a native form for 20th-century use. The first exchanges in the Low Countries had been open courtyards. Berlage kept that basic idea with glass-roofed trading halls surrounded by brick arcades.

After 1913 Berlage became “house architect” for the wealthy Kröller-Müller family and designed several innovative buildings, including the Holland House in London and St. Hubertus near Otterlo. The London building code required that Berlage cover Holland House’s steel frame. He chose terra-cotta plates to fill the space and frame the windows. Inside, movable walls divided the office space. Both were innovations. St. Hubertus was an extravagant hunting lodge; its plan takes the form of stylized antlers in reference to the story of St. Hubertus and the stag. The monumental conception has been linked to Wright’s designs.

After 1920 Berlage’s work began to favor geometry even more vigorously. The best examples of this are the First Church of Christ, Scientist, and the Municipal Museum, both in The Hague. Both buildings are assemblages of cubic prisms in which geometry replaces historical quotations. Another late work is the Amstel Bridge, designed as part of his plan for Amsterdam South. The bridge was a joint effort between Berlage and the city engineer’s office and was praised by contemporaries as a socially productive collaboration between state and artist promising cooperation for the future. It combines a decorated bridge with park space for water recreation.

Both 19th-century theorists and 20th-century innovators influenced Berlage. He drew inspiration from Gottfried Semper and Viollet-le-Duc, who admired the organic harmony and holistic creativity of great architecture of the past but who also criticized the cut-andpaste pattern-book copying that had come to dominate 19th-century architecture. Similarly, Berlage argued that the architect should shape useful spaces rather than decorate facades. In his view, a building should express its function from the interior outward rather than allow surface details to dictate room arrangement. Through lectures and essays describing his American travels, Berlage was the first major European architect to publicly declare his interest in the American innovations of Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright. Wright’s work particularly affected Berlage, confirming the path toward geometric architecture that he had already begun.

Berlage is thus an excellent example of an architect negotiating between the ancients and the moderns. He was interested in developing a newer architectural vocabulary in step with the 20th century while also retaining links to the historical past. His best-known works are modern but based in traditional forms. After 1890 he began to decorate his buildings with geometric, stylized historical motifs. Preferring simple materials to imitations and noting that “genuine plaster is better than false marble” (Over stijl in bouw - en meubelkunst, 1904), he liked to use materials in accordance with their natural features. Conversely, he disliked bentwood and the plaster concealment of structural elements, as the exposed iron supports in the trading rooms of the Amsterdam Exchange demonstrate. Berlage was especially fond of brick, a material traditionally associated with Dutch architecture. He retained this link to the past, but he used brick in unorthodox ways, particularly by exposing it as an interior wall element in residences, for example, the Villa Henny (1898) in The Hague. Brick gave mass, strength, and an organic pattern to architectural designs that were intrinsic to the material, not an applied ornament.

Berlage believed that the architect had a social responsibility to improve living conditions. Consequently, beginning around 1900, his interests expanded to include city planning as a means of social amelioration, resulting in expansion plans for several Dutch cities, of which only the plan for South Amsterdam (1915–17) was implemented. Social concerns affected Berlage’s interior design as well, which is known for its geometric focus. He explicitly avoided the vegetative forms popular with Art Nouveau designers, such as Victor Horta and Henri van de Velde in Belgium, and he was a founder of the anti-Art Nouveau reform design store ‘t Binnenhuis (the Interior). He was interested in higher aesthetic standards for ordinary objects such as furniture, carpets, books, dishes, and wall coverings and made many designs. His work influenced De Stijl designers, although there was periodic hostility between Berlage and leading figures associated with De Stijl. |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| TIMELINE |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

21 February 1856 Born in Amsterdam;

1874–75 Studied painting, Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam ;

1875–78 studied architecture under Gottfried Semper’s followers at the Bauschule, Eidgenössische Polytechnikum (now Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule), Zurich ;

1879 traveled Germany ;

1879 Worked in Arnhem, Netherlands ;

1880–81 traveled Italy ;

1881–84 associate, later designer, office of Theodorus Sanders, Amsterdam ;

1887 Married Marie Bienfait ;

1889–1934 partnership with Sanders 1884–89; private practice, The Hague and Amsterdam ;

after 1899, became involved primarily in urban planning;

1913– 19 worked for Müller and Company, traders, Rotterdam ;

1932 Awarded Gold Medal, Royal Institute of British Architects ;

12 August 1934 Died in The Hague. |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| FURTHER READING |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Bazel, K.P.C. de, et al., Dr. H.P.Berlage en zijn werk, Rotterdam: Brusse, 1916 Berlage, Hendrik Petrus, Dr. H.P.Berlage, bouwmeester, Rotterdam: Brusse, 1925

Bock, Manfred, Anfänge einer neuen Architektur: Berlages Beitrag zur a rchitektonischen Kultu r der Nieder lande im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert , Wiesbaden: Steiner, and The Hague: Staatsuitgeverij, 1983

Bock, Manfred, H.P.Berlage en Amsterdam, Amsterdam: Meulenhoff/Landshoff, 1987; as H.P.Berlage in Amsterdam, Amsterdam: Architectura and Natura Press, 1992

Polano, Sergio, Hendrik Petrus Berlage: Opera completa, Milan: Electa, 1987; as Hendrik Petrus Berlage: Complete Works, translated by Marie-Hélène Agüeros and Mayta Munson, London: Butterworth, and New York: Rizzoli, 1988

Reinink, Adriaan W., Amsterdam en de Beurs van Berlage: Reacties van tijdgenoten (with English summary), The Hague: Staatsuitgeverij, 1975

Singelenberg, Pieter, H.P.Berlage: Idea and Style: The Quest for Mode rn Architecture, Utrecht: Haentjens Dekker and Gumbert, 1972 (an important monograph)

Singelenberg, Pieter, H.P.Berlage, bouwmeester, 1856–1934 (exhib. cat.), The Hague: Haags Gemeentemuseum, 1975

Selected Publications

Over stijl in bouw - en meubelkunst, 1904 Gedanken über den Stilin der Baukunst, 1905

Grundlagen und Entwicklung de r Architekt ur, 1908

Het uitbreidingsplan van ’s Gravenhage, 1909

Studies over bouwkunst, stijl en samenleving, 1910

Beschouwingen over bouwkunst en hare ontwikkeli ng, 1911 “Neure amerikanische Baukunst,” Schweizerische Bauzeitung, 60, nos. 11–13 (1912) “Art and the Community,” The Western Architect, 18 (1912) “Foundations and Development of Architecture,” The Western Architect, 18 (1912) Amerikaansche reisherinneringen, 1913

Normalisatie in woningb ouw, 1918

Schoonheid in samenleving, 1919

Hendrik Petrus Berlage: Thoughts on Style, 1886–1909 (a translated anthology), 1996 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| RELATED |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Art Nouveau; BRICK; De Stijl; Horta, Victor (Belgium); Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig (Germany); Oud, J.J.P.(Netherlands); Rietveld, Gerrit (Netherlands); van de Velde, Henri (Belgium); Wright, Frank Lloyd (United States) |

| |

| |

|