|

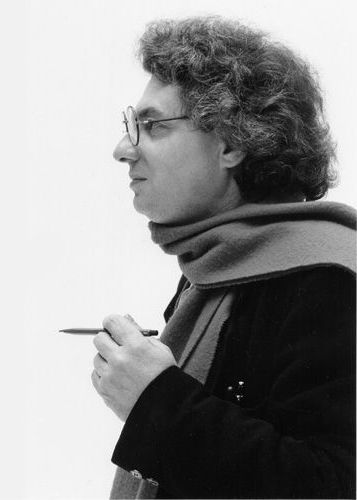

| MARIO BOTTA |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Name |

|

Mario Botta |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Born |

|

April 1, 1943 |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Died |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Nationality |

|

Switzerland |

| |

|

|

|

| |

School |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Official website |

|

www.botta.ch |

| |

|

|

| |

| BIOGRAPHY |

|

|

| |

|

Mario Botta gained architectural fame during the early 1970s when he began designing small houses in the Ticino region of Switzerland.

Botta completed an apprenticeship with Tita Carloni and architectural studies in Milan and Venice, prior to opening his own office in 1969. The houses he designed during the early 1970s established the Ticino school and changed Swiss architec-ture dramatically. It is largely because of Botta’s innovative work that the present generation of Swiss architects is internationally acclaimed.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, the Ticino region changed from a primarily agricultural economy, to an industrial one that emphasizes tourism. The primary cause of this change was the integration of this region into the European highway system at the beginning of the 1960s. Most of the Ticino architects built for the wealthy bourgeoisie who profited from the economic change, and Botta’s first commissions came either from clients to whom he was recommended by his mentor Carloni, or from his relatives. In addition, he participated in competitions, either alone or with older colleagues, such as Luigi Snozzi, Carloni, and Aurelio Galfetti.

The Ticino school generates its designs from architectural and contextual requirements. Architecturally, the buildings exhibit their materials and construction openly. Simple forms characterize typical examples, with a focus on mass and contour line, and ornamentation derived from structure and construction technology. Contextually, these designs attempt to relate the old to the new. The old comes from architectural typology and the vernacular traditions, and the new stems from building technology. In addition, these architects intend to express a mythical topography of the Ticino region, or what is termed the natural calling of the site. This architecture attempts to continue the trends (tendenza) already apparent in the organization of the land, and to realize them in an architecture conceived as an act of culture, which incorporates geometry and history.

For Botta, the dignity of architecture results not from intuition, but from architecture’s own rules and from history. He proposes that history is the place where architecture finds and defines its meaning. Form and meaning are determined through the relationship to historical buildings, especially the local Romanesque and baroque churches. New meanings can be derived only from these familiar themes, and it is only secondarily that meaning is created through sociocultural usage. Botta’s designs aim to contrast physical, social, and cultural traditions to the transient phenomena of modern life.

Botta began in the 1960s, with designs that were inspired by the postwar work of his idols: Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn. During the 1970s, he transformed his theories into buildings that had a strong formal quality. The Bianchi House (1973) in Riva San Vitale is a mysterious, isolated tower that stands up to the surrounding mountains. It is defined by corner supports and a roof slab, and allows outside views by increasing the opening of the construction shell as it rises. The confrontational position of the house to its site emerges in the entrance bridge, which articulates the detachment between natural and man-made, resulting in stark, bizarre forms.

Botta’s buildings impress through their strong image quality, which might be interpreted as cultural resistance intent on a new order and meaning. The houses are devoid of clustered compositions or extensions. The massive exterior walls establish a sharp datum. Through such devices, the Casa Rotonda (1981) in Stabio establishes an unexpected presence within an anonymous context. The building is derived from geometric form. The seemingly impenetrable, cylindrical shape contrasts with the large cuts in its surface and suggests an opposition between fortification and openness. The Casa Rotonda questions our assumptions concerning the nature of dwellings; conventional or traditional elements are eliminated. Moreover, everything is subordinated to form. The interior is laid out symmetrically around the central slot of the stairwell and skylight, and rooms are irregular, leftover spaces resulting from inserting a rectangular grid into the house’s cylinder.

In larger designs, the geometrical forms became megastructures. The Middle School (1977) in Morbio Inferiore, uses a bridge typology for the arrangement of its eight classroom clusters. The complex is an orderly architectural composition with openings, covered areas, porticoes, and passages. Modular units are repeated to generate the overall shape, and to make the organizational structure of the building easily apparent. A spatially diverse, skylit central passage creates a rich variety of spaces inside this simple form.

In the State Bank (1982) in Fribourg, Botta managed to fit his building into an existing urban situation. A protruding cylindrical volume dominates a public square, and turns the corner while the two receding wings relate to the rhythm and scale of the buildings on the flanking streets. Botta used this approach of dividing a large building into different shapes and facade articulations frequently during the 1980s.

In the late 1980s, the images of the facades became dominant in Botta’s buildings; they became figures in which typical details from his earlier designs were re-used. In his Union Bank (1995) in Basel, the facade, curved toward the square, impresses as a heavy bastion. It opens into a cavity that is partly filled by a massive pier on a broad base. Although such shapes are appropriate for a bank building, they become disturbing when used for other building types. The large cubical forms used for the Housing Complex (1982) in Novazzano appear to be without scale and meaningless, because they are not finished in Botta’s traditional brick veneer. The absence of this craft surface reveals the emptiness of these forms.

A disappointing aspect of Botta’s architecture is that most of his buildings seem to embody the same vision. Now, his repetitive cylinders have appeared in all parts of the world for the most diverse functions, such as museums, churches, single-family homes, shopping centers, and office buildings, as well as in his furniture designs and household appliances.

HANS R.MORGENTHALER

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1. Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005 |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| TIMELINE |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

1 April 1943 Born in Mendrisio, Switzerland;

1958–61 Apprentice building draftsman, office of Carloni and Camenisch, Lugano, Switzerland ;

1961–64 attended the Liceo Artistico, Milan ;

1964–69 studied under Guiseppe Mazariol; attended the Istituto Universitario de Architettura, Venice;

1965 studied under Carlo Scarpa. Assistant to Le Corbusier, Venice and Paris ;

1969 received a degree in architecture ;

from 1969 Private practice, Lugano;

1978 Member, Federation of Swiss Architects ;

1982–87 member, Swiss Federal Commission for the Fine Arts;

from 1983 Professor, École Polytechnique Federal, Lausanne, Switzerland;

1983 honorary fellow, Bund Deutscher Architekten ;

1984 honorary fellow, American Institute of Architects;

1987 visiting professor, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut ;

1989 committee member, International Course for Architectural Planning, Andrea Palladio International Centre for Architectural Studies ;

1991 member, Acádemie d’Architecture, Paris . |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| FURTHER READING |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

A fairly complete and well-illustrated three-volume catalog of Botta’s work has recently been published (Pizzi, 1993–98). Botta’s designs usually receive ample coverage in architectural magazines, while scholarly articles are scarce.

Abrams, Janet, “Mario Botta’s San Francisco Museum of Modern Art,” Lotus International, 86 (1995)

Bedaria, Marc, “The House of Culture of Chambery: An Example of Decentralization,” Lotus International, 43 (1984)

Botta, Mario, and Enzo Cucchi, La cappella del Monte Tamaro: The Chapel of Monte Tamaro (bilingual Italian-English edition), Turin: Umberto Allemandi, 1994

Carloni, Tita, “Architect of the Wall and Not of the Trilith,” Lotus International, 86 (1983)

Dimitri, Livio, “Architecture and Morality—An Interview with Mario Botta,” Perspecta, 20 (1983)

Frampton, Kenneth, “Mario Botta and the School of the Ticino,” Oppositions, 14 (Fall 1978)

Musi, Pino, and Marco d’Anna, Mario Botta: Public Buildings, 1990–1998, edited by Luca Molinari, Milan: Skira, 1998

Nicolin, Pierluigi, Mario Botta: Buildings and Projects, 1961–1982, New York: Rizzoli, and London: Electra/Architectural Press, 1984

Pizzi, Emilio, Mario Botta, Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 1991

Pizzi, Emilio, Mario Botta: The Complete Works, 3 vols., Zurich: Artemis, 1993–98

Purini, Franco, “Inner Voices: Observations on Architecture and Mario Botta,” Lotus International, 48–49 (1986)

Zardini, Mirko, The Architecture of Mario Botta, New York: Rizzoli, 1985

Selected Publications

“Architecture and Environment,” A+U (June 1979)

“Swiss Transmission and Exaggerations” (interview), Skyline, 2/8 (1980)

“Ein Raum für Guernika,” Werk, Bauen und Wohnen, 11 (1981)

La Casa Rotonda, 1982

MORE BOOKS |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| RELATED |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Corbusier, Le (Jeanneret, Charles-Édouard); Kahn, Louis |

| |

| |

|