|

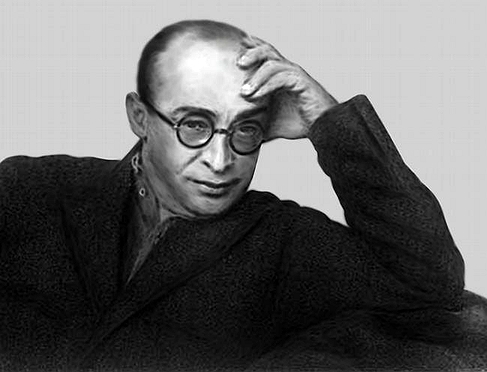

| MOISEI GINZBURG |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

Name |

|

Moisei Yakovlevich Ginzburg |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Born |

|

June 4, (O.S. May 23), 1892 |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Died |

|

January 7, 1946 |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Nationality |

|

Russia |

| |

|

|

|

| |

School |

|

CONSTRUCTIVISM |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Official website |

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| BIOGRAPHY |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Moisei Iakovlevich Ginzburg was the leading theoretician of Constructivism in architecture, a prolific designer, and a pioneer in the research and construction of collective housing. Ginzburg was born in Minsk, the capital of Belorussia, where his father was practicing architecture. Upon high school graduation, young Moisei departed for France to study. After a brief period in Paris at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and in Toulouse at the Art Academy, he enrolled in the architecture program of the Academia di Belle Arti in Milan, Italy, graduating in 1914. The outbreak of World War I forced him to return via the Balkans to Moscow, where he continued his education at the Riga Polytechnic (evacuated to Moscow during the war), earning a degree in architectural engineering in 1917.

A man of enormous energy and with a desire for continuous learning, Ginzburg departed for the Crimean peninsula to head the office for the preservation of cultural monuments and to investigate Tatar folk architecture. He returned to Moscow in 1921 and published a series of articles on Tatar art. He devoted the following years to pedagogical and scholarly work, teaching at the Moscow Institute for Civil Engineering (MIGI, later MVTI) and the Higher Artistic-Technical Studios (Vkhutemas). A member of the State Academy of Artistic Sciences, he headed an expedition to Bukhara, Uzbekistan in 1924 and during the following year traveled to Turkey. He published two theoretical works on architecture before becoming a founding member of the Society of Contemporary Architects (OSA) and editor (with Alexander Vesnin) of the society's journal, Sovremennaia arkhitektura (Contemporary Architecture) from 1926 to 1930.

During his student years, Ginzburg encountered French Art Nouveau, Italian futurism, and the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Moscow in the early 1920s was the center of contending avant-garde factions, where European avant-garde periodicals were available. For example, the trilingual magazine Vesch/Gegenstand! Object, initiated in 1922 in Berlin by El Lissitzky (1890-1941) and Ilya Ehrenburg (1891-1967), related Soviet trends to their Western counterparts. Ginzburg’s first building in Moscow, the Crimean Pavilion at the First Agricultural and Handicraft Exhibition (1923), was inspired by the picturesque asymmetry of traditional Tatar houses. He also aimed at abstracting the underlying principles that shaped folk architecture and defining the “distinct creative order” concealed behind its “picturesque spontaneity.” He clarified this creative order in his theoretical work Ritm v arkhitekture [Rhythm in Architecture], published in 1923, and Stil i epokha (Style and Epoch), published the following year.

Vkhutemas was a testing ground for new aesthetic ideas. Ginzburg wrote his Ritm v arkhitekture as a pedagogical tool for his course on the theory of architectural composition. He analyzed the rhythm of architectural styles and the harmonious relationships between architectural forms. He defined harmony as “the mathematical essence of rhythm,” supporting his claim with concepts from the physiology of visual perception. Ginzburg also compared proportional relationships in architecture to harmonious “chords consisting of melodious notes” in music. He began working on Style and Epoch while Ritm v arkhitekture was near publication, thus responding to the former to “express the rhythmical pulse of our time.” Present dynamic trends are best manifested in new technologies, Ginzburg believed, and therefore he took the machine as a paradigm for modern functional design. He devised a system of vector diagrams to demonstrate “the dynamic content” of previous architectural styles compared with “a contemporary architectural concept” embedded in the 1923 Palace of Labor competition entry by the Vesnin brothers. Accordingly, the form and sense of dynamic movement is best captured in asymmetrical architectural compositions symbolizing “a previously unknown tension.” Although Ginzburg did not elaborate his concept of rhythm and dynamism in subsequent publications, his concrete designs relied heavily on these constructs.

Ginzburg continued to clarify and develop the theoretical foundations of Constructivism through the pages of Sovremennaia arkhitektura. For him, the functional method integrated all possible aspects of architectural considerations into design solutions, including “the national uniqueness” of architecture. His 1926 project for the House of the Soviets in Makhachkala, the capital of the Dagestan Autonomous Republic, accounted for the inferences of persistent climatic and biological conditions that sustain life and have defined the specific national aspect of each republic. Although Ginzburg did not win this competition, his design for the center of Alma-Ata, the new capital of Kazakhstan, placed first the following year. This urban public space was surrounded by the House of Government, the Turkestan-Siberian Railroad Administration (1899-1974, both designed by Ginzburg and his student Ignatii Milinis), and the House of Communications (1897-1972, designed by Georgi Gerasimov). Each building, a dynamic asymmetrical composition of several volumes, contained a semiprivate interior courtyard. Roof terraces provided magnificent views of the surrounding mountains.

After building an apartment and communal housing block (1927) in Moscow, Ginzburg was appointed in 1928 to organize and head the Standardization Section of the Construction Committee (Stroikom RSFSR). His group produced five types of housing units in several variations for prefabrication and speedy assembly all over Russia. The most economical type, yet novel in its spatial qualities, was immediately built in Moscow (1928—31), for the Commissariat of Finances (Narkomfin). This housing type was used by several OSA members in their subsequent projects and by Ginzburg in the workers’ housing (1931) in Rostokino, near Moscow. It became fashionable among European intellectuals because of Le Corbusier's housing blocks based on similar apartment units.

Ginzburg also headed the Section for Socialist Resettlement and participated in the 1929 Green City Resort competition. His project, a model for transforming Moscow into a green city, consisted of ribbons of prefabricated housing units and transportation-commercial-cultural nodes forming community centers. Although several experimental units were built (1931), this project never materialized. None of his major competition projects—the Palace of Soviets in Moscow (1932), the Synthesizing Theater in Sverdlovsk (1932), and the Commissariat of Heavy Industry in Moscow (1934) —was realized. Yet they influenced modern architectural thought in Russia and Western Europe.

After all architectural organizations were disbanded and the official Union of Soviet Architects was formed in 1932, Ginzburg was elected to the board. From 1933 on, he headed a design studio in the Commissariat of Heavy Industry (Narkomtiazhprom), and when the Soviet Academy of Architecture was established in 1939, he was among its first academicians. Ginzburg became editor and contributor to the academy's multivolume Vieobshchaia istoriia arkhitektury (1940-45; History of World Architecture). In 1945, he headed the academy's team charged with the planning and restoration of Crimea. He died on January 7, 1946 as the work began.

Mika BLIZZNAKOV

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.2 (G-O). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| TIMELINE |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

23 May 1892 Born in Minsk, Russia;

1914 Attended Ecole des Beaux-Arts, Paris; attended Ecole d’Architecture, Toulouse; studied under Gaetano Moretti, Academia di Belle Arti, Milan;

1914 received an engineering degree from Rizhsky Polytechnic, Moscow;

1918-21 Private practice, the Crimea;

from 1923 founder, editor, contributor, Vieobshchaya istoriya arkbitektury. Professor, Vkhutemas, Moscow;

from 1923 instructor, Moscow Institute of Higher Technology;

1923 editor, Arkbitektura;

1925 Member, Moscow Architectural Society; member, Russian Academy of Artistic Sciences; founding member, Association of Contemporary Architects (OSA);

1926-30 founder and editor, with Aleksandr Vesnin, Sovremennaia arkhitektura;

from 1933 member, design studio, Heavy Industry Commissariat;

1937 member, First Congress of Soviet Architects ;

1939 academician, Soviet Academy of Architecture;

1941-45 head, Sector for Standardization and Industrialization of Construction;

7 January 1946 Died in Moscow. |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| FURTHER READING |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

Although Moisei Ginzburg is mentioned and/or in every book on Constructivism, no book about him in English exists.

Blisnakov, Milka, "Rhythm as a Fundamental Concept of Architecture” Experiment: A Journal of Ruslan Cube, 2 (1996)

Bliznakov, Milka, "Soviet Housing during the Experimental Years, 1918-1933," in "Russian Housing in the Modern Age: Design and Social History", edited by William Brumfield and Blair Ruble, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993

Buchli, Victor, "Moisei Ginzburg's Narkomfin Communal House in Moscow: Contesting the Social and Material Weld,” Journal of the Sociery of Archintsnnel Flieorkans, 57/2 (1998)

Cooke. Catherine, Rauian Avant-Garde: Theories of Ars, Architecture, and the City, London: Academy Editions, 1995 (includes translations of several articles by Ginsburg published in the journal Sovremennaya arkitektura)

Khan-Magomedov, Selim O., "M.Y, Ginsburg.” Architetural Design", 2 (1970)

Khan-Magomedov, Selim O., Moisey Ginzburg, Milan: Angeli, 1977; 2nd edition, 1983

Khan-Magomediy, Selim O., Pioneers of Soviet Architecture: The Search for New Solutions in the 1920s and 1930s, translated by Alexander Lieven, edited by Catherine Cooke, New York: Rizzoli, and London: Thames and Hudson, 1987

Kopp, Anatole, L'architecture de la période salinienne, Grenoble, France: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, 1978; as Constructivist Architecture in the USSR, London: Academy Editions, and New York: St. Martin's Press, 1985

MORE BOOKS |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| RELATED |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

|