| ALL |

|

INDIA

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Twentieth-century architecture in India is a product of diverse regional practices and historical precedents, the country's colonial legacy, and the policies adopted by the independent state. Individual aspirations, as well as visions of the collective—nation, class, and religious affiliation—have also left their imprints on this matrix. The proliferation of stylistic labels in recent discussions of 20th-century architecture in India—Indo-Deco, Anglo-Indian modern, neovernacular, and Bania-Gothic—some invoked more humorously than others, indicate not only the multiple agencies at work but also the problem of description. More specifically, this is a conceptual problem of situating Indian architecture in the matrix of global culture and the century-long effort to tease out what is "Indian."

Far from being a monolithic construct, the multifarious notions of Indian identity shifted numerous times during the century. Certain assumptions, however, underlay all discussions of architecture: that modernity had no original roots in India and was of European import, implying that Modern architecture in India was derivative; that any notion of Indian architecture must retain a connection to the traditional architecture of the country, in contrast to Euro-American modernism, which claimed a break with the past; and finally, that the task of Indian architects was to develop a regional vocabulary. The first assumption was based on British colonial discourse that viewed Indian culture as static and maintained that any change must be due to foreign influence. Although Indian nationalists argued that change could be homegrown, most viewed groundedness in pre-British tradition as a necessary condition for modern Indian identity. Those, such as Jawaharlal Nehru, India's first prime minister, who deviated from this norm, ensured that Le Corbusier's modernist design of Chandigarh would be treated as a watershed in Indian architecture. The changing ideology of state patronage in independent India, from a modern international outlook after independence to a modern valorization of Indian tradition since the 1980s, has invited narratives of Indian architecture that construct the latter as a sign of independence and originality. A small coterie of Indian architects who are central to this late-20th-century development have ensured through writings and interviews that their work is understood within frames of reference set by themselves, most importantly, that these acts of tradition are read back as universal gestures (and not simply as the application of universal principles to a local vocabulary, creating a variation on a modernist theme). In a larger perspective, this ability to determine the narrative of contemporary architecture is a significant change from the beginning of the century, when Indian architects operated with limited power under colonial rule.

Pre-independence Architecture

At the beginning of the century, the major cities showcased the work of the reigning Anglo-Indian firms, such as Martin and Co. in Calcutta, William A. Chambers and Co., Hall and Batley in Mumbai (then Bombay), and Jackson and Barker in Chennai (then Madras). The establishment of architectural education programs (the J.J. School of Arts in Mumbai augmented its five-year diploma in 1913) as well as the formation of the Indian Institute of Architects in 1929 increasingly formalized professional practice. By the 1920s, more and more Indian architects were securing commissions, and architectural firms, such as Master, Sathe, Bhuta, and Maherwanjee Bana and Co. in Mumbai, enjoyed the patronage of wealthy Indian industrialists.

In terms of architectural design, some important changes were taking place. Designers in urban areas were responding to new technology, such as electrical lighting, elevators, and the widespread use of indoor plumbing, and to changing conceptions of privacy and gender structure in both European and Indian residences. The three-bay bungalow plans with a hall in the center and two rows of rooms on either side and its counterpart, the urban courtyard house, were being replaced by a larger variety of house plans that used bay windows, oblong rooms, and rounded verandas. Designers clearly intended to distinguish between the use of rooms and wed corridors for separating functions and people. The practice of aggregating spaces in terms of use and incorporating an elaborate network of passages had already transformed the plans of institutions and office buildings. Now a classical treatment of the exterior, the hallmark of respectability in the early 19th century, and the official neo-Gothic and Indo-Saracenic were supplemented with a number of stylistic variations inspired by Art Deco and an inquiry into the Indian architectural vocabulary. The New India Assurance Building (1935) in Mumbai, a reinforced-concrete structure by Master, Sache, Bhuta, was a symbol of the modern outlook in business adopted by the Tata Company, a leading Indian industrial house. It was meant to be distinguished from its contemporaries, such as the Statesman House (1931) in Calcutta by Sudlow, Ballardic, and Thomas, and the late 1920s projects for the Indian Tobacco Company on Chowringhee Road by Martin and Co. The latter had conventional parti and attempted to fit into the colonial neoclassical surroundings. In contrast, the Assurance Building had an open plan, then synonymous with business efficiency, and a forced-air cooling system that was complemented by adequate natural ventilation as a contingency plan.

The bold vertical elements of this six-story facade competed with the new building type, the movie theatre, which also used this Art Deco treatment to emphasize a novel identity. Buildings such as the Eros Cinema in Mumbai, designed by Sohrabji K. Bhedwar in the 1930s, also cropped up in Calcutta, Chennai, Patna, and other cities. Located at prominent street locations with highly illuminated facades, theaters were designed to convey the fantasy world of movies. The entrance foyer, bar and lounge, and sweeping staircases were dressed in marble and adorned with murals, etched glass, and chandeliers. These public spaces were one of the few places the middle class could celebrate an elegant life. For a section of the growing middle class, at least, there was a domestic counterpart to the Modern approach to design exemplified by the Assurance Building and the cinemas. The architects of numerous residential projects between the 1930s and 1950s resorted to fluid lines in designing the building envelope. This aesthetic agreed with the need to provide continuous shade over windows and with the building codes that stipulated uniform setbacks to render coherence to the street view and yet allowed individual residences to project modern aspirations of the nuclear families for which they were designed. Apartments in the Back Bay in Mumbai and detached residences in Ballygunge in Calcutta are classic examples of this era.

Although this kind of domestic architecture has become inseparable from Indian middle-class respectability, to contemporary architects, such as Sris Chandra Chatterjee (1873-1966), their looks did not denote Indianness. He advocated "an internal arrangement suitable for modern life" but a decorative program directly derived from ancient Indian architecture. Pattern books, such as A.V.T. Iyer's The Indian Architecture (1926), recommended "a proper national style" by adapting colonial building types to reflect classical Indian notions of beauty. This was contrary to 19th-century residential designs for the Indian middle class in which a traditional parti was augmented by a "modern" neoclassical facade. If in the 19th century the inner space of domestic life was considered the repository of Indian values, that identity was now to be translated into a clearly recognizable vocabulary on the public face. Of course, Chatterjee's ideas were not restricted to residential design alone; his suggestions for banks and educational institutions demonstrated the attempt to define a "Greater Indian Order" by assimilating elements from different regions and eras of India's ancient architecture. Chatterjee's vision, documented in the "Draft Manifesto for the Proposed All-India League of Indian Architecture," found a number of prominent supporters but was not persuasive enough to determine the narrative of Indian architecture.

The desire to define a national language of architecture appropriate for the 20th century came out of the swadeshi movement. Swadeshi (national), a response to British economic and cultural domination, meant the rejection of foreign goods and support for native industries. This swadeshi quest in the arts was grounded in a "new Orientalism" that found enduring aesthetic merit in India's ancient (mainly "Hindu") tradition and believed in a revival of that tradition as the necessary basis for modern Indian art, as opposed to its 19th-century British Orientalist view that belittled this tradition. The swadeshi spirit in architecture, however, took various forms, from a championing of the local vernacular to pan-Asianism. The Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1905) injected confidence in Asian power and a desire for pan-Asian solidarity in the arts. A remarkable celebration of such a pan-Asian aesthetic was the residence of Nobel laureate poet and novelist Rabindranath Tagore in Santiniketan, Bengal.

Tagore established a school (later to become Visva Bharati University) at Santiniketan with the objective of providing an education that would be nurtured in an idyllic natural surrounding reminiscent of the ancient forests (tapovan) where the sages of the Vedas were said to have resided. He rejected the unimaginative regimen of the British school system and its urban moorings in Calcutta. Of the many residences that were designed for Tagore by Surendranath Kar with the aid of Nandalal Bose and the poet's son Rathindranath Tagore, the largest was named "Udayan" (facing the rising sun). The multilevel design of the building (1919-28) was developed in several phases, and its unusual qualities resided in the attempt to break out of the confines of the room as a unit of habitation. Its staggered terraces reached out to "connect with nature" from various vantage points, and its eclectic decorative program was intended to create different moods in different spaces and owed much to Japanese wood interior. The richness of

the decoration was also hierarchically layered, with decorative features disappearing at the topmost level, where the empty form alone would provide repose. The ideas embedded in the house plan appear to have stepped out of the gender hierarchies of the 19th-century Calcutta mansion where he grew up (with its separation between the inner apartments for women and outer apartments for men), but the necessity of a laboring population to serve the master house had not disappeared. A substantial single-story building, housing a kitchen, storage, and servants' quarters, was constructed as a separate attached structure. Although not conventionally "revivalist," Udayan was as much a symbol of the nation as it was of the emergent poet's personality.

The use of Indian references in such well-known buildings was invariably perceived as a political statement in light of the planning process of New Delhi (1911-31). The neobaroque plan of New Delhi and the design of the capitol buildings by Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker were meant to impress British resolution to rule India despite Indian nationalist agitation. The new capital, with its insistent differentiation along lines of race, class, and occupation, was to enshrine in stone the relation between the rulers and the ruled.

Postindependence Practices

The independent state inherited impressive monuments in New Delhi as well as an inadequate physical infrastructure, a weak economic and industrial base, and a massive housing shortage. The latter was exacerbated by the influx of refugees from Pakistan following the bloody partition of the country at the cost of independence. Primary industries, power generation, self-sufficiency in food grains, and housing were national priorities. As a socialist democracy, the state shouldered the responsibility for much of the building activity that took place in the formal sector. The state's intervention had a profound influence over architectural expression throughout the rest of the century.

Instead of making Indian motifs secondary to the building program, as in the case of Lutyens's design, architects after independence, at the behest of politicians, made them central to their schemes. If the oversized entrance to the Vigyan Bhavan (1955) in New Delhi by R.I. Gehlote demonstrated the possibility of manipulating ancient formal elements while keeping the thread of historical association intact, the abundant decorations in the Vidhana Soudha (1952-57) in Bangalore strove to assert the viability of traditional building craft in India. The architects of Mysore's Public Works Department sought out experts in the decorative arts of the South and constructed a building shunning new materials, such as glass and steel. The latter stood opposite the neoclassical High Court (1865) and replicated its plan and section in spirit. A decorative program paying tribute to Kannada culture adorned the building's profile and structural members. The proud originator of this idea, Kengal Hanumanthiah, the chief minister of Mysore (present-day Karnataka), is memorialized in front of the building, standing with a model of the building in the palm of his hand. The building program, the siting, and the sculpture were telling of the identity and power at stake in the newly formed nation-state. Viewed from one angle, Hanumanthiah's conception of the building offered less resistance to the British colonial legacy than it did to the modernist architectural vision that was unfolding contemporaneously in Chandigarh. From another perspective, it demonstrated that the formal conception was often not the most important platform for expressing independence. Rather, it was the question of who had the power to make decisions regarding major financial and cultural investments.

The most celebrated example of state-sponsored construction was the planning of Chandigarh (1951-57), the capital of the new states of Punjab and Haryana. At the invitation of Jawaharlal Nehru, the Department of Public Works appointed Le Corbusier and a team of consultants—Pierre Jeanneret, Jane Drew, and Maxwell Fry—to design the city and several important buildings. The largest commission of Le Corbusier's life became an opportunity to explore his notions of a modern city and modern monuments. The spacious 1200-by-800-meter city grid with its low-density built form was designed with an affluent car-owning citizen in mind and ignored lessons from contemporary Indian urbanism. Taken together, the Assembly Building, the Secretariat, and the High Court presented an array of formal possibilities of reinforced concrete in a context that offered brilliant sunshine and manual labor. Considered individually, their object-like presence, the pragmatic concerns of users, and the weather-worn concrete expose the lapses in design consideration. Nehru had supposedly intended Chandigarh as shock therapy for the nation—an expensive way to exorcise the ghost of colonialism that continued to haunt the policies and politics in the region for years to come. Formal experiments in modernism, however, were not new in India. The Dining Hall (1947) of the Institute of Science in Bangalore by Otto Koenigsberger, the New Secretariat (1944-47) in Calcutta by Habib Rahman, the Shodhan House (1939, now demolished) in Ahmedabad by Armaram Gajjar, and the Golconda (1936-48) in the Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry by Antonin Raymond predated Chandigarh, as did many others. Chandigarh differed from these examples in the objectives and the scale of undertaking and in the charisma of the architect himself but most of all in the explicit ideology that accompanied it. Nehru had supported other approaches to architecture as well, many of which were conspicuous in their "traditional" references. However, it was not traditional forms but the social premise and cultural baggage that accompanied the forms that he found problematic. He was contemporaneously fighting legislative battles to keep in place his vision of a secular democracy that did not discriminate on the basis of caste, class, gender, or religion with the excuse of tradition. Although he did not determine (nor did any one individual) all the aspects of city planning or building design, Nehru envisioned Chandigarh as his political legacy, the daring to experiment with new ideas, and his belief that a new democracy deserved a novel architectural form.

The architectural imaging of Nehru's vision of a modern, industrial nation found several subscribers and continued well into the 1970s. Achyut P. Kanvinde's design for the Milk Processing Plant (1974) at Mehsana relied on a heroic gesture of turning the ordinary and mechanical functions of a factory into a theatrical interplay of form and light. Few examples, however, were more telling of national architectural aspirations and limitations than the commission for the Permanent Exhibition Complex for the 1972 Trade Fair in New Delhi. The building designs by Mahendra Raj, an architect turned structural engineer, and Raj Rewal were contemplated as steel space frames to span 78- and 44-meter modules unencumbered by supports. Ultimately, it was constructed of reinforced concrete when the cost of steel construction proved prohibitive.

The more mundane cult of the concrete—a brick-filled reinforced-concrete frame with a concrete flat-slab roof and concrete ledges and shades—used en masse in government housing projects and institutions became the most common language of architecture across the country. Invariably distinguished into income groups—

higher, middle, and lower income—hundreds of housing projects for government employees and for sale at subsidized rates were laid down on gridded plans. Some of the privately sponsored residential projects, such as the Tara Group Housing (1978) in New Delhi, deviated from the previously mentioned mechanistic schemes. Designed by Charles Correa, Jasbir Sawhney, and Ravindra Bhan, the project consisted of 160 double-story row house units (varying from 84 to 130 square meters) built on 3-by-15-meter modules. The residential units were staggered in both plan and section along an internal landscaped "street." The street acted as a "humidifying zone" conducive to social interaction. High-density low-rise housing and the vocabulary of courtyards, chowks (streets), and mohallas (pedestrian alleys) became the mainstays of housing design in the 1980s. Raj Rewal's design for the Asiad Village (1982) in New Delhi took this vocabulary to its extreme. The Village, built for the 1982 Asian Games, consisted of 700 units that later became apartments for high-income tenants. The units were clustered in groups of 12 to 36 units around a common space, with terraces for outdoor living and sleeping, and gateways were formed by overhanging residential units that attempted to provide variety to the repetitive pattern.

At the other end of the socioeconomic scale, housing solutions met with glaring limitations. To meet the demand for housing for the poor, government development agencies promoted user-initiative programs in "sites-and-services" projects. The cost of infrastructure—roads, water supply, wastewater drainage, and a small toilet—were borne by the agency, and the construction of the individual dwelling was left to the individual owner. The Integrated Urban Development project (1975) in Ahmedabad by Kinee Shah, designed for flood refugees, attempted to provide dwelling units as well as opportunities for education and supplementary employment. The design, developed on the basis of architect-owner participation, consisted of two-room units made of exposed brick and roofed with asbestos cement sheets. The veranda and a shared courtyard worked as outdoor living/work space. The viability of these projects was circumvented by their location away from cities and employment opportunities, and two-thirds of the targeted economically disadvantaged population could not even afford these subsidized projects. Consequently, migrants to the cities continued to swell the population of squatter settlements and slums.

Most architects recognized that the housing shortage was not just a design problem but one that required a drastic reconsideration of basic issues of resources, employment, and social equity. Nonetheless, the problem of low-cost housing continued to be addressed by most architects as a design challenge—discovering low-cost forms and low-cost technology that necessitated an inquiry into vernacular building practices. In the ashrams at Sabarmati (1918) in Ahmedabad and at Sevagram (1930s) in Maharashtra, Mahatma Gandhi had used traditional construction to demonstrate its viability, and these became touchstones for a generation of post-independence architects. The simple rectangular buildings at Sevagram were mud-on-timber-frame constructions on a stone foundation. Pitched timber roofs with tiles, a few bamboo columns, spacious verandahs, and small fenestration covered with slatted bamboo screens completed the ensemble.

Laurie Baker, an English emigrant to India, inspired by Gandhi's vision, built a large repertoire of buildings that eschewed contemporary design fads and were rooted in an appreciation of the resourceful vernacular architecture of Kerala. His design for the Center for Development Studies (1975) in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, was developed to demonstrate responsible building practices. A vocabulary of exposed local bricks for walls and screens, wood and concrete for structural members, and ceramic tiles for roofs was rendered in simple but elegant details. Concrete was used economically, often substituted with rejected clay tiles in the lower tension portion of slabs. The most lavishly detailed building was the guesthouse, where the brick jali (lattice) screens were accompanied by carefully crafted woodwork.

Considerations of climate and local building practices led Uttam Jain to explore a completely different vocabulary in Rajasthan, one that was shaped in large measure by an allegiance to modernist principles. In the buildings of the Jodhpur University campus (1971), Jain used dressed yellow sandstone in lime mortar to give the buildings a rugged feel. In the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, stair-towers and voids for cross lighting punctuated the double-loaded corridors of a conventional U-shaped plan. The load-bearing, glazed inner wall was shaded by an outer wall to reduce the heat load and render the building a sculptural quality. Jain's Indira Gandhi Institute for Development in Mumbai (1987) asserts a similar relationship between building and site; this research complex with residences for staff and scholars coalesces around open courtyards and green space.

It was the space-structure relationship of vernacular traditions that most architects found useful for their modern buildings. Charles Correa's design for the Gandhi Smarak Sangrahalaya (1957) in Ahmedabad exploited the versatility of the courtyard typology and included a concern for climate, human scale, and history. By the 1980s, the critical acclaim of Correa's designs, the design of the Indian Institute of Management (1972) at Ahmedabad by Louis Kahn, and the campus designs that followed (such as the Indian Statistical Institute, 1981, in New Delhi by Anant Raje and the Indian Institute of Management, 1983, at Bangalore by Balkrishna Doshi) ensured not only a significant change in the design of the institutional campus (compared to the Institute of Technology campuses in Kharagpur, Kanpur, and New Delhi and scores of that ilk) but also the establishment of an Indian modern vocabulary. Academic facilities around a spacious courtyard or amphitheater, shaded networks of "streets," diagonal axes of movement, broken symmetries, and the bold geometry of locally quarried stones or bricks on a reinforced-concrete structural system were the leitmotifs of these institutional designs. The austere aesthetics and the monumentality of these projects were softened in the experiments with typology in smaller academic complexes. The preference for a more intimate scale in designing institutional projects was related to the establishment in the 1980s of a number of agencies to study and conserve physical and cultural resources. These were small, semi-autonomous academic and research institutes that desired an architectural image in harmony with changes in concerns about sustainability. The Center for Development Studies (1987) in Pune by Christopher Beninger; the Inter-University Center of Astronomy and Astrophysics Center (1998) by Charles Correa; the Entrepreneurship Development Institute (1987) by Bimal Parel and the Center for Environmental Education (1990) by Neelkanth Chhaya and Kallol Joshi, both projects located in Ahmedabad; and the Visitors Hostel (1990) at the Nehru Science Center in Bangalore by Chandravarkar and Thacker adapted a domestic scale that was integrated with the landscape.

Repositioning Indian Identity

One of the most innovative precedents that integrated landscape and architecture was Balkrishna Doshi's studio and architectural foundation Sangath (1980). The building consisted of two sets of parallel barrel-vaulted structures, partly subterranean, and the totality integrated with a carefully designed landscape. The vaults were made of cylindrical terra-cotta tiles sandwiched between thin ferro-cement shells. The external surface of the vaults was animated by a heat-reflecting waterproof covering of china mosaic. Water channels between vaults carried rainwater to reflecting pools and the garden. Although the cooling effect of the form and materials was limited in the Ahmedabad summers, the design and ideas presented through lyrical drawings and thumb sketches signified a departure from the modernist vocabulary of Indian architects: here, a concern for typology, material, climate, and form was squarely located in the realm of India's architectural tradition.

The centrality of "tradition" in a newly emerging narrative was evident in two architectural exhibitions in 1986. The first, titled "Vistara" (vistas/openings), was exhibited in Mumbai and was designed for the Festival of India tour abroad; the second, titled "Kham" (space/pause), was organized by the Indira Gandhi National Center for the Arts (IGNCA) in New Delhi. Whereas the first attempted to locate contemporary architecture in the continuum of India's architectural history, the second suggested multisensorial "acts" of space and commonalities between India's preindustrial architecture with those around the world. Both emphasized the role of myths in architecture and everyday life (including myths of modernity and industrialization) and claimed an aesthetic universality that was simultaneously grounded in regional practices and tradition. These were professional designers' attempts to designate acceptable sources and practices and to craft an Indian Modern style that claimed to have come to terms with the past.

The political climate that supported these ideas wrestled with the reemergence of tradition as a political problem. Although tradition in the revival of Indian crafts and advertising tourist destinations was profitable and found an eager audience among international tourists and the Indian bourgeoisie, the logic of tradition in the religious nationalisms that were attempting to tear apart the secular democracy needed to be confronted. In demonstrating links between the great architecture of different eras and emphasizing their metaphysical dimensions, one could pass over the political difficulties facing the architect when dealing with troubled historical legacies (e.g. the recent ones of British colonialism) and overlook sociopolitical fractures in the contemporary fabric of the country. Not surprisingly, in the brief of the international design competition for the IGNCA complex (1986) in New Delhi, the overwhelming theme was one of assimilation. The Center, a cultural complex of museums, performance, and education facilities, was intended to be a memorial to Indira Gandhi, who was assassinated in 1984 by Sikh militants demanding a separate homeland. The Center was to articulate a unique all-encompassing, "Indian worldview (which in the brief passed as "Hindu" worldview) to launch Gandhi as one of the canonical figures of Indian nationalism equated with some of the mainstays of the nationalist movement in British India. Situated in the heart of Lutyens's New Delhi, this complex was to harmonize with the colonial surroundings. Ralph Lerner's winning entry, a Lutyenesque response to the brief, was commended for maintaining "a necessary connection with history." Here, historical connections necessarily resided on the surface.

Similarly, an investigation of folk architecture central to the new interest in tradition could only include questions of form and beauty. In such a view, the "typical" Indian village and the historical architecture of the country were seen as the repository of a universal good, notwithstanding the caste, class, and gender dynamics that inhabit(ed) and influence(d) these forms. Revathi and Vasanth Kamath's design for the Tourist Village at Mandawa (1986) in Rajasthan was conceived as sun-dried mud-brick- and -thatch structures replicating the anthropomorphic village forms of the Shekhawati region. The client, the rajah of Mandawa, was hard to convince—he wanted a pucca (masonry) construction for his investment, preferably one that looked like a Canadian resort. The architects convinced him to adopt the regional vocabulary of mud architecture, "not only cheap but also the most appropriate way, both climatically and aesthetically." It was a place for the international tourist looking for the Indian village experience without the squalor and inconvenience and one in which folk artisans and performers could market their traditional skills. The architect here is not only the arbiter of taste but also is responsible for decoding and interpreting cultural memories and reviving traditional building practices forgotten by the Dubai-returned local masons. The client's and the architect's aspirations were not that different—both borrowing distant images to produce an object, an experience for consumption, each in their way crafting a contemporary Indian identity with their imaginings of a good life.

Creating an architecture rooted in tradition when images from across the world are easily accessible through television and the Internet is a difficult proposition at best. In a country in which most buildings are not designed by design professionals, many Indian architects have resorted to myths to distinguish their work from that of the contractor-builder and the transient middle-class consumers who apply architectural forms to residences and commercial complexes as objects of desire culled from the global economy. For example, in narrating the meaning literally underlying the design concept for the Bharat Diamond Bourse (1998) in Mumbai, Balkrishna Doshi spoke of spiritual rather than corporate revelations. The three-million-square-foot mega-complex consists of nine towers clad in mirrored glass located on a landscaped base of granite outcrop. The tightly secured walled-in complex was constructed with the aspiration to compete in the lucrative global diamond market. Doshi, however, imagined the rocky site as having mythical origins and claimed that the complex is now the "most sacred site in India" and a "true sanctuary." This sort of myth-making romanticizes what was otherwise a blatant commercial project and might well forebode a very different landscape in the 21st century.

SWAT CHATTOPADHYAY

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.2 (G-O). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

7th century CE, Kailashanatha Temple, Kanchipuram, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

8th century CE, Shore Temple, Mahabalipuram, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

10th century CE, Nataraja Temple, Chidambaram, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

10th century CE, Mukteshwar Temple, Bhubaneswar, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

11th century CE, Brihadishwara Temple, Thanjavur, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

11th century CE, Modhera Sun Temple, Modhera, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

11th century CE, Jain Temple, Palitana, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1199-1236, Quṭb Mīnār, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

13th century CE, Keshava Temple, Somanathapura, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1235, Tomb of Iltutmish, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1325, Jāmiʿ Masjid, Cambay, India |

| |

|

| |

, Cambay, India.png) |

| |

1325, Jāmiʿ Masjid (interior), Cambay, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Mid-14th century, Tomb of Rukn-i ʿĀlam, Multan, Pakistan |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1352, Ḥauz-i Khāṣṣ, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Early 15th century, Sharza Darwāza, Bidar, India |

| |

|

| |

, Dhar, India.png) |

| |

1405, Lāt Masjid (interior), Dhar, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1408, Atalā Mosque, Jaunpur, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1420, Tomb of Fīrūz Shāh Bahmanī, Gulbarga, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1424, Jāmiʿ Masjid, Ahmadabad, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1439, Tomb of Hūshang Shāh, Mandu, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1444, Tomb of Muḥammad Shāh Lōdī, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

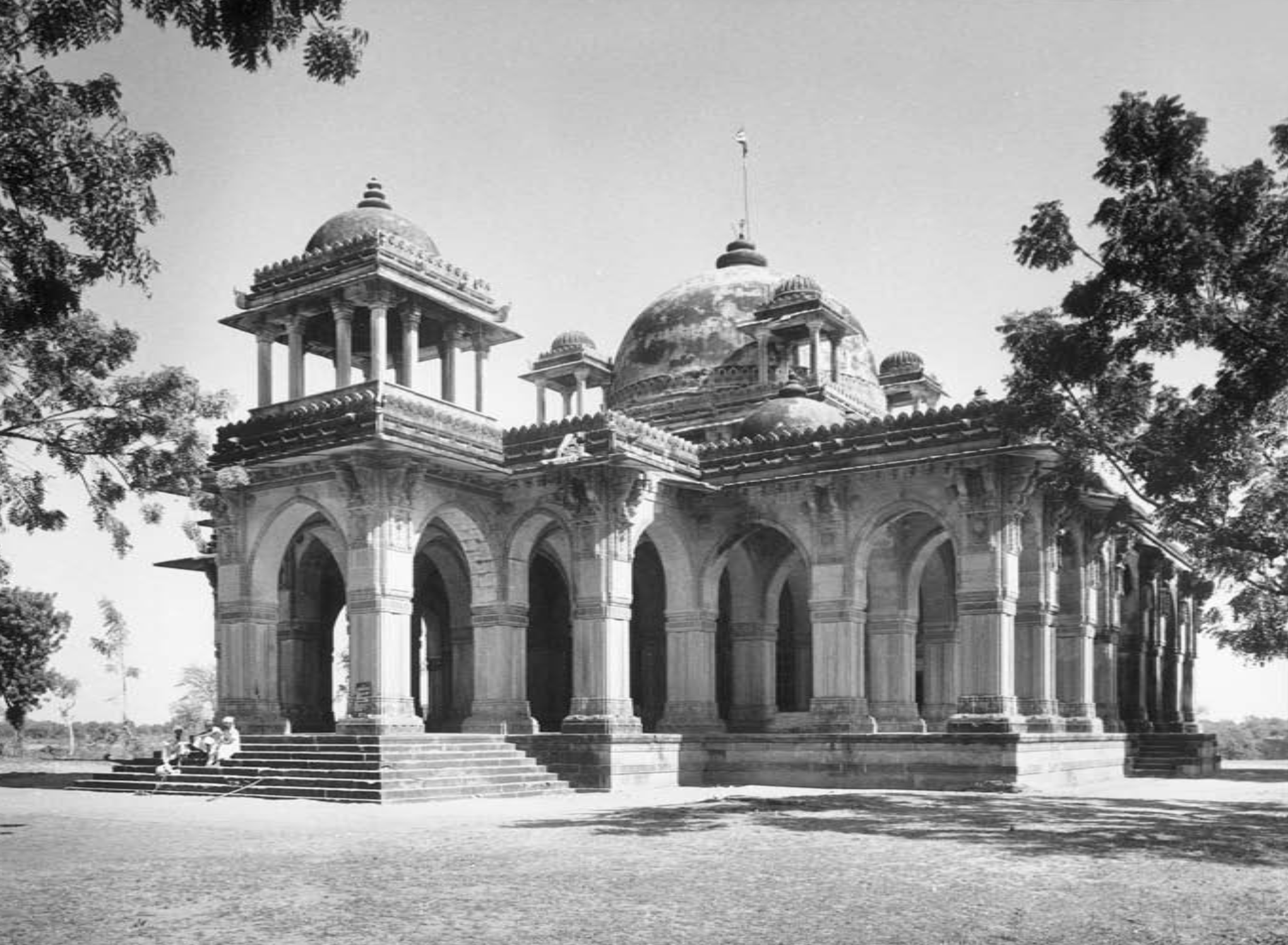

1454, Jāmiʿ Masjid, Mandu, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1465, Mosque of Miyān Khān Chishtī, Ahmadabad, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Early 16th century, Water Sluice, Sarkhej, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1517, Shīsh Gunbad, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1514, Tomb of Rānī Sabrāʾī, Ahmadabad, India |

| |

|

| |

, Ahmadabad, India.png) |

| |

First quarter of the 16th century, Bābā Luluiʾs Mosque (façade detail), Ahmadabad, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1540-1555, Purānā Qilʿa, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1541, Qilʿa-i-Kuhnā Masjid, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1545, Tomb of Shēr Shāh Sūrī, Sasaram, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

After 1562, Tomb of Muḥammad Ghaus, Gwalior, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1570s, Pānch Maḥall, Fatehpur Sikri, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1572, Mosque of Sidī Saʿīd, Ahmadabad, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1579, Tomb of ‘Alī Barīd, Bidar, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

After 1588, Tomb of Sayyid Mubārak Bukhāri, Mahmudabad, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1588-1589, Tomb of Humāyūn, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1613, Tomb of Akbar at Sikandra, Agra, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1626, Ibrāhīm Rauza, Bijapur, India |

| |

|

| |

, Bijapur, India .png) |

| |

1626, Ibrāhīm Rauza (façade detail of tomb), Bijapur, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

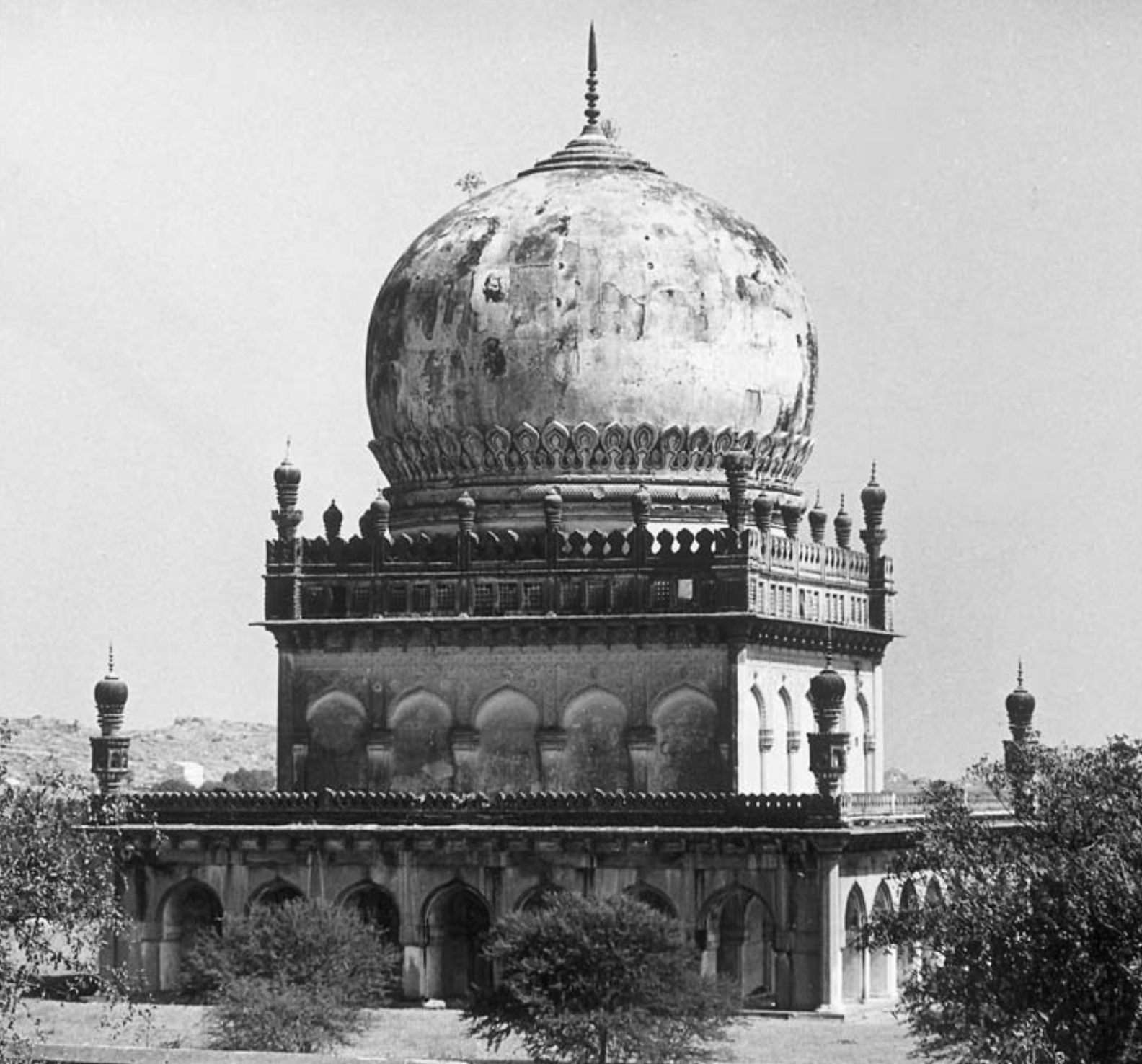

1626, Tomb of Muḥammad Quṭb Shāh, Golkonda, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

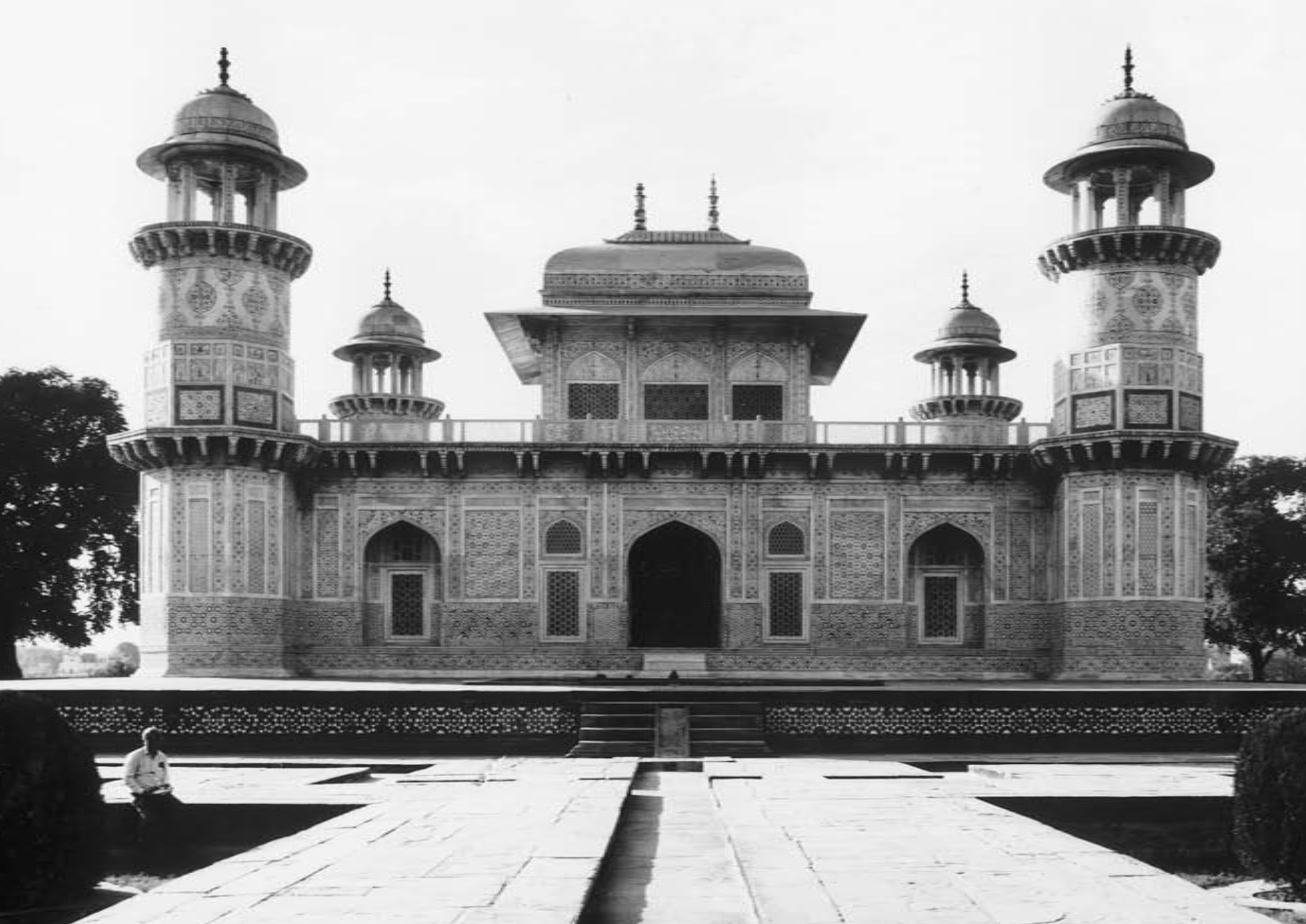

1628, Tomb of Iʿtimād ad-Daula, Agra, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1632-1643, Tāj Maḥall, Agra, India |

| |

|

| |

, Agra, India.png) |

| |

1632-1643, Tāj Maḥall (south portal), Agra, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1639-1648, Dīwān-i Āmm, Lāl Qilʿa, Delhi, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1650-1656, Jāmiʿ Masjid, Agra, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

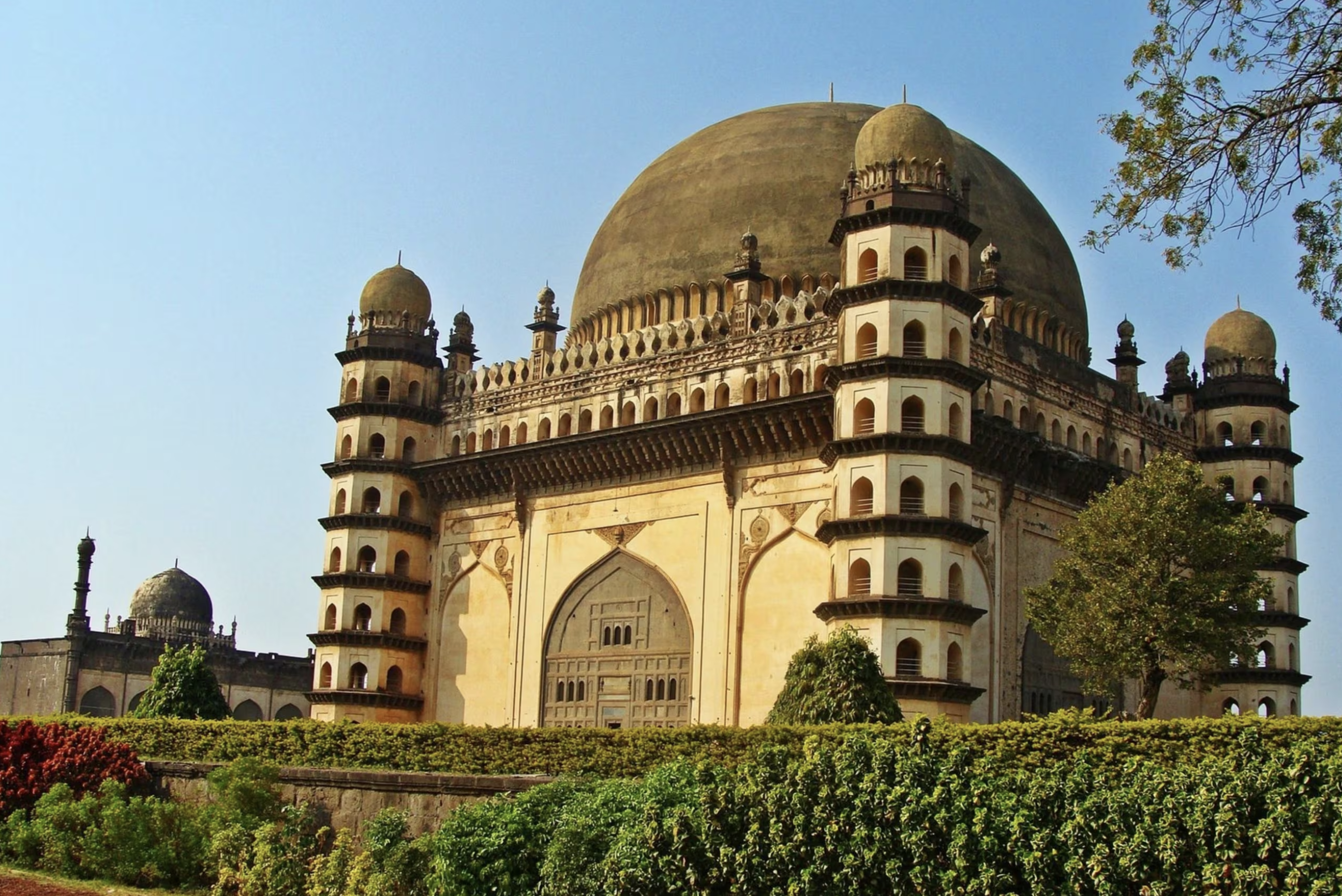

1656, Gol Gunbad, Bijapur, India |

| |

|

| |

, Aurangabad, India.png) |

| |

1661, Tomb of Rābiʿa Daurānī (“Bībī kā Maqbara”), Aurangabad, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1671, Tōlī Mosque, Hyderabad, India |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1902, Lalgarh Palace, Bikaner, India, Sir Samuel Swinton Jacob |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1905, The Prince of Wales Museum, Bombay, India, George Wittet |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1909, The National Art Gallery, Madras, India, Henry Irwin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1912, Amba Vilas Palace, Mysore, India, Henry Irwin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1952, Complexe du Capitole, Chandigarh, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1954, Building of the Mill-Owners' Association, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1955, Sarabhai House, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1956, Shodan House, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1957, Ahmedabad Museum, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

, Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI.jpeg) |

| |

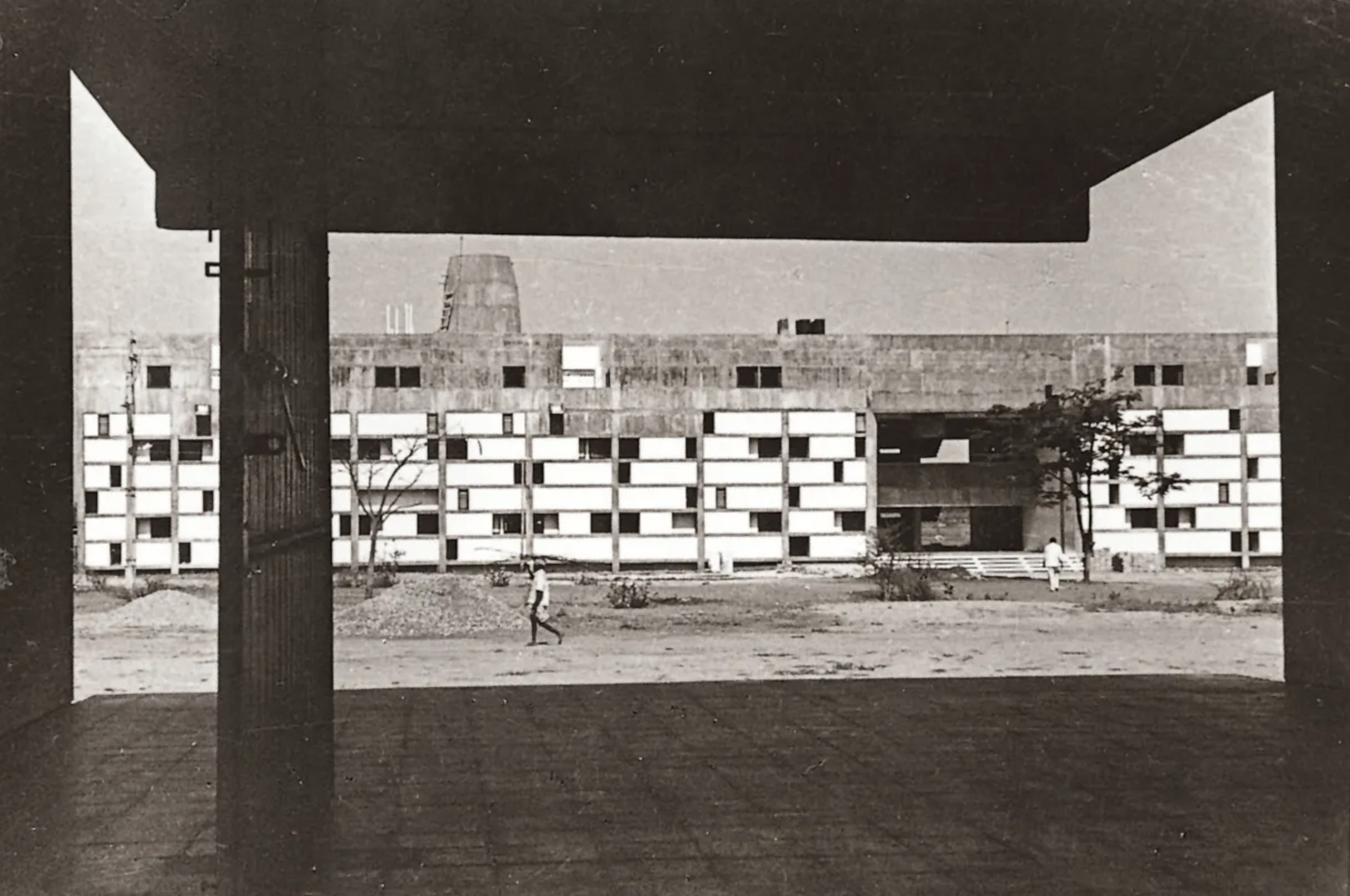

1957, Low-cost housing for workers of the Ahmedabad Textile Industry Research Association (ATIRA), Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1957-1962, Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1958, Secretariat, Chandigarh, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

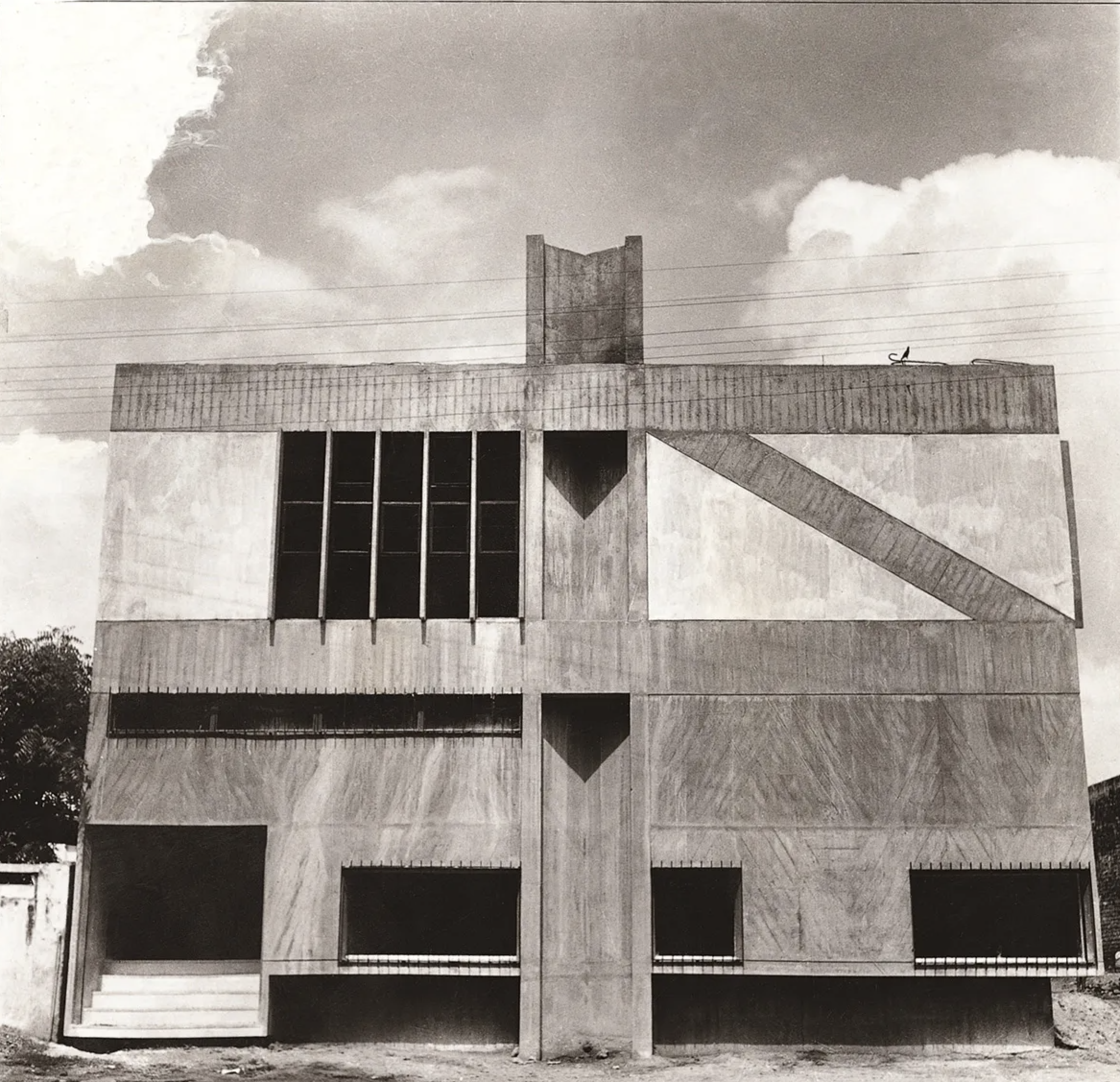

1958-1960, ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, ANAND, GUJARAT, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1960-1962, GUN HOUSE, AHMEDABAD, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1962-1975, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1967-1968, PAREKH HOUSE, Ahmedabad, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1970-1982, Sheikh Sarai Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1970-1983, KANCHANJUNGA Apartments, MUMBAI, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1972-1976, Premabhai Hall, Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1973-2015, Delhi Television Centre, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1976-1989, STATE TRADING CORPORATION, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1977, Nehru Science Centre, Mumbai, India, Achyut Kanvinde |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1978-1983, ENGINEERS INDIA HOUSE, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1980-1989, SCOPE COMPLEX, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

, Bhopal, India, Achyut Kanvinde.png) |

| |

1982, Indian Institute of Forest Management (IFM), Bhopal, India, Anant Raje |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1984-1986, Supreme Court Co-Operative Group Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1989-2000, CHURCH AT PARUMALA, KERALA, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1992-1995, Husain-Doshi Gufa, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1996-2002, Offices “Tata Consultancy Services”,

New Delhi, India, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

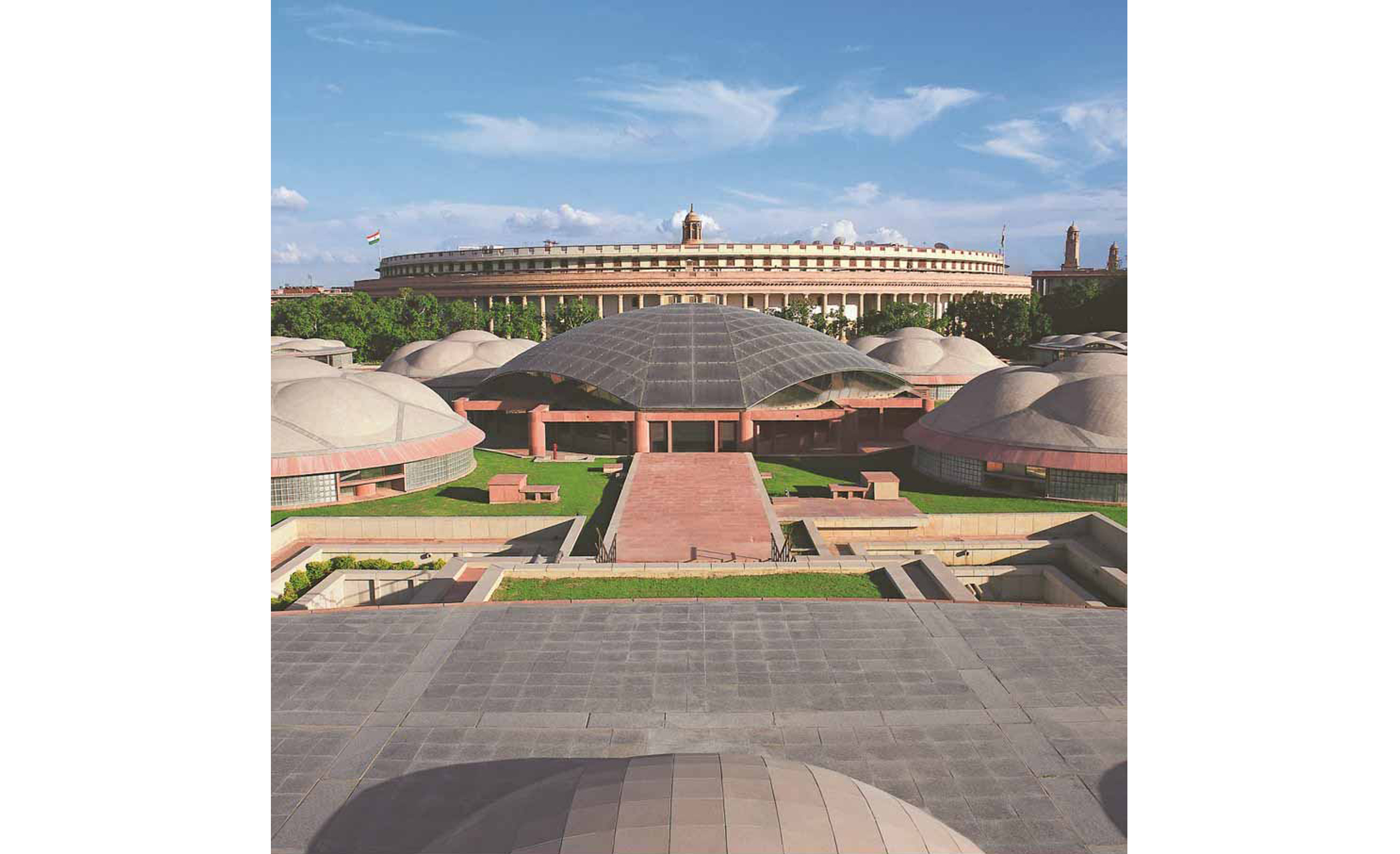

2003, Library for the Indian Parliament, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

, Ahmedabad, India, HCP Design and Project Management Pvt. Ltd..jpeg) |

| |

2006, Indian Institute of Management New Campus (IIM), Ahmedabad, India, HCP Design and Project Management Pvt. Ltd. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2014, Jung-e-Azadi Memorial Complex, Karatpur, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2011, Virasat-e-Khalsa Museum,

Anandpur Sahib, Punjab, India, MOSHE SAFDIE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

ARCHITECTS: INDIA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1952, Complexe du Capitole, Chandigarh, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1954, Building of the Mill-Owners' Association, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1955, Sarabhai House, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1956, Shodan House, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1957, Ahmedabad Museum, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1957, Low-cost housing for workers of the Ahmedabad Textile Industry Research Association (ATIRA), Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1957-1962, Institute of Indology, Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1958-1960, ADMINISTRATION BUILDING, ANAND,

GUJARAT, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

1958, Secretariat, Chandigarh, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1960-1962, GUN HOUSE, AHMEDABAD, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

1962-1975, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

1964-1969, Township for Gujarat State Fertilizers, Baroda (Vadodra), INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1968, School of Architecture, Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1967-1968, PAREKH HOUSE, Ahmedabad, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

1970-1982, Sheikh Sarai Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1970-1983, KANCHANJUNGA Apartments,

MUMBAI, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

1972-1976, Premabhai Hall, Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1973-2015, Delhi Television Centre, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1976-1989, STATE TRADING CORPORATION, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1978-1983, ENGINEERS INDIA HOUSE, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1979-1981, Sangath, architect’s own office, Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1980-1984, Gandhi Labor Institute, Ahmedabad, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1980-1989, SCOPE COMPLEX, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1983-1986, Aranya low-cost housing, Indore, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1984-1986, Supreme Court Co-Operative Group Housing, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

1989-2000, CHURCH AT PARUMALA,

KERALA, INDIA, CHARLES MARK CORREA |

| |

|

| |

1992-1995, Husain-Doshi Gufa, INDIA, BALKRISHNA V. DOSHI |

| |

|

| |

1996-2002, Offices “Tata Consultancy Services”, New Delhi, India, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

2003, Library for the Indian Parliament, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

2014, Jung-e-Azadi Memorial Complex, Karatpur, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

2011, Virasat-e-Khalsa Museum,

Anandpur Sahib, Punjab, India, MOSHE SAFDIE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

CHANDIGARH; LE CORBUSIER; NEW DELHI;

FURTHER READING

Made in India, (Architectural Design November December 2007, Vol. 77, No. 6)

Ashraf, Kari Khaleed, and James Belluardo (editors), An Architecture

of Independence. The Making of Modern South Ari, New Yock:

Architectural League of New York, 1998

Behrendt, Kurt A, The Buddhist Architecture of Gandhara, Brill, 2003

Bhatia, Gautam, Panjabi Baroque and Other Memories of

Architecture, New Delhi and New York: Penguin, 1994

Bhatt, Vikram, and Peter Scriver, After the Masters, Ahmedabad,

India: Mapin, 1990

Burton, John, Indian Islamic Architecture: Forms and Typologies, Sites and Monuments (Handbook of Oriental Studies Handbuch Der Orientalistik. Section 2 India), Brill Academic Publishers, 2007

Bussagli, Mario and Calembus Sivaramamurti, 5000 Years of the Art of India, Harry N. Abrams

Bussagli, Mario, Oriental Architecture: v. 1 (History of World Architecture), Electa/Rizzoli, 1989

Bussagli, Mario, Oriental Architecture: v. 2 (History of World Architecture), Electa/Rizzoli, 1989

Chatterjee, Malay, "The Evolution of Contemporary Indian

Architecture," in Architectures m Inde, edited by Jean-Louis

Véret, Paris: Electa Moniteur, 1985

Coomaraswamy, Ananda Kentish , Essays in early Indian architecture, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 1992

Dengle, Narendra, Dialogues with Indian Master Architects, The Marg Foundation, 2015

Evenson, Norma, Chandigarh, Berkeley: University of California

Press, 1966

Evenson, Norma, The Indian Metropolis: A View towards the West,

New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1989

Gast, Klaus Peter, Modern traditions: contemporary architecture in India, Birkhäuser Architecture, 2003

Fergusson, James and Phené Spiers, History of Indian and eastern architecture Vol. 1, John Murray, 1910

Fergusson, James and Phené Spiers, History of Indian and eastern architecture Vol. 2, John Murray, 1910

Grover, Sarish, Building beyond Borders Story of Contemporary Indian

Architecture, New Delhis National Book Trust India. 1995

Guha-Thakurta, Tapati, The Making ofa New "Indian" Are: Artists,

Aesthetics, and Nationalism in Rengal, c. 1850-1920, Cambridge

and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992

Havell, Ernest Binfield, Indian architecture: its psychology, structure, and history from the first Muhammadan invasion to the present day, S. Chand, 1972

King, Anthony, "India's Past in India's Present: Cultural Policy and

Cultural Practice in Architecture and Urban Design, 1960-

1990,' in Perceprions of South Asia's Venual Past. edited by

Catherine Ella Blanshard Asher and Thomas R. Mercalf. New

Delhi: American Institute of Indian Studies, 1994

Kulbhushan, Jain, Thematic space in Indian architecture, AADI Centre; India Research Press, 2002

Lang, Jon T., Madhavi Desai, and Miki Desai. Architecture and

Independence. The Search for Identity India. 1880 to 1980. Delhi

and New York: Oxford University Press, 1997

Sohoni, Pushkar, Taming the Oriental Bazaar: Architecture of the Market-Halls of Colonial India, Routledge, 2023

Thapar, Bindia, Introduction to Indian Architecture, Periplus Editions, 2005

Tillorson, Giles Henry Rupert, The Tradition of Indian Architecture:

Continuit, Controversy, and Change since 1850. New Haven,

Connecticur: Yale University Press, 1989

Tillorson, Giles Henry Rupert, Paradigms of Indian Architecture: Space and Time in Representation and Design, Routledge, 1997

Volwahsen, Andreas, Living Architecture: Indian, Hennessey & Ingalls, 1969

|

| |

|

|