| ALL |

|

GLASS

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Glass results from heating a mixture of sand, lime, and sodium carbonate to a very high temperature. When different materials are added to the sand, glass can become transparent, translucent, or colored. While the origins of glass are shrouded in mystery, the Ancient Egyptians are traditionally credited with its invention, given their use of faience even before Egypt was unified into dynasties. Faience, a form of glass paste that is fired, was used by Egyptians to make small beads and to decorate clay pottery. The famous small blue hippopotamus, located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, dates to about 1800 BC and illustrates this technique. Objects made entirely of glass date to the New Kingdom, beginning in 1550 BC when glassmaking was limited to the royal workshops and created only for the royal families. These earliest glass objects are core glass in which a clay model was formed, wrapped in cloth strips, placed on a skewer, and then dipped in molten glass. The clay was removed via the hole left by the skewer, and then small bits of colored glass were heated and molded into thin strips to be attached to the glass core in decorative patterns. Small animal-shaped vessels that held scented oils were often made of core glass during the Egyptian 18th Dynasty.

Architectural glass, however, was not introduced until the Romanesque period of the 11th century when transparent and translucent glass was used for window coverings that allowed for the introduction of light or even for interior liturgical partitions. The earliest method for creating glass windows was called the crown glass technique. In this case, a round piece of hot-blown glass was cut away from the pipe and then spun around rapidly until it flattened out like a thin pancake. The piece would then be cut entirely off its pipe and shaped into smaller pieces that would fit into iron frames. This type of glass reveals a characteristic bull’s-eye at the center point, where it remained attached to the pipe while being spun. Later, more sophisticated cutting of the crown glass resulted in a diamond-shaped piece, which reduced the distortion created by the varying thickness of the crown glass and allowed for a more intricate pattern of fenestration. Only in the 19th century was this process finally replaced by a less expensive process of creating sheet glass, which allowed for larger individual windowpanes. This type of glass still has subtle variations in thickness that are apparent in older buildings today, where one can see the effect of rippling on the glass. Float glass, used today for windowpanes, is a process invented in the 1950s and 1960s by the manufacturer Sir Alastair Pilkington of Pilkington Glass in England. Float glass provides the smoothest surface, is the least expensive flat glass to produce, and is used in architectural construction across the world.

Joseph Paxton’s Crystal Palace, built for the 1851 London Exhibition, established a technological as well as a philosophical interest in creating a glass house. In 1938, Walter Gropius used thick glass blocks to create an entire exterior wall for his own house built in the Bauhaus style in Lincoln, Massachusetts, and in 1946 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe used a large single pane of glass to cover the façade of the Farnsworth House near Plano, Illinois. Philip Johnson took this idea to its conclusion with the construction of his own house made almost entirely of glass. His so-called “Glass House,” built in New Canaan, Connecticut, in 1949, is often considered one of the most beautiful but least functional houses in the world. Free from constraints of a clientele, function, or money, Johnson created an exceptional home of glass walls set into a concrete frame and with concrete flooring. All the interior rooms flow together, and no interior walls touch the glass exterior. The bathroom is enclosed in a brick cylinder in the center of the small rectangular house, while the rest of the home enjoys privacy from its rural setting.

By the mid-20th century, large glass windows had become common in domestic architecture. The Ranch-style house, for example, is characterized by both the use of larger glass windows and glass-pane sliding doors. These larger sheets of movable glass then necessitated the development of laminated and tempered glass to prevent their shearing into jagged strips if broken. Instead, this shattered glass holds together in a spider-web pattern. More varieties of chemically strengthened glass continue to be produced today to allow for further architectural possibilities, including not only the use of glass curtain walls on skyscrapers but also load-bearing glass walls that are more energy-efficient and soundproof.

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.2 (G-O). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1851, Crystal Palace, London, UK, Joseph Paxton |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1937, Gropius House, LINCOLN, MASSACHUSETTS, USA, Walter Gropius |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1949, Glass House, New Canaan, USA, Philip Johnson |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1951, Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, USA, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1962, Bell Laboratories, Holmdel, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

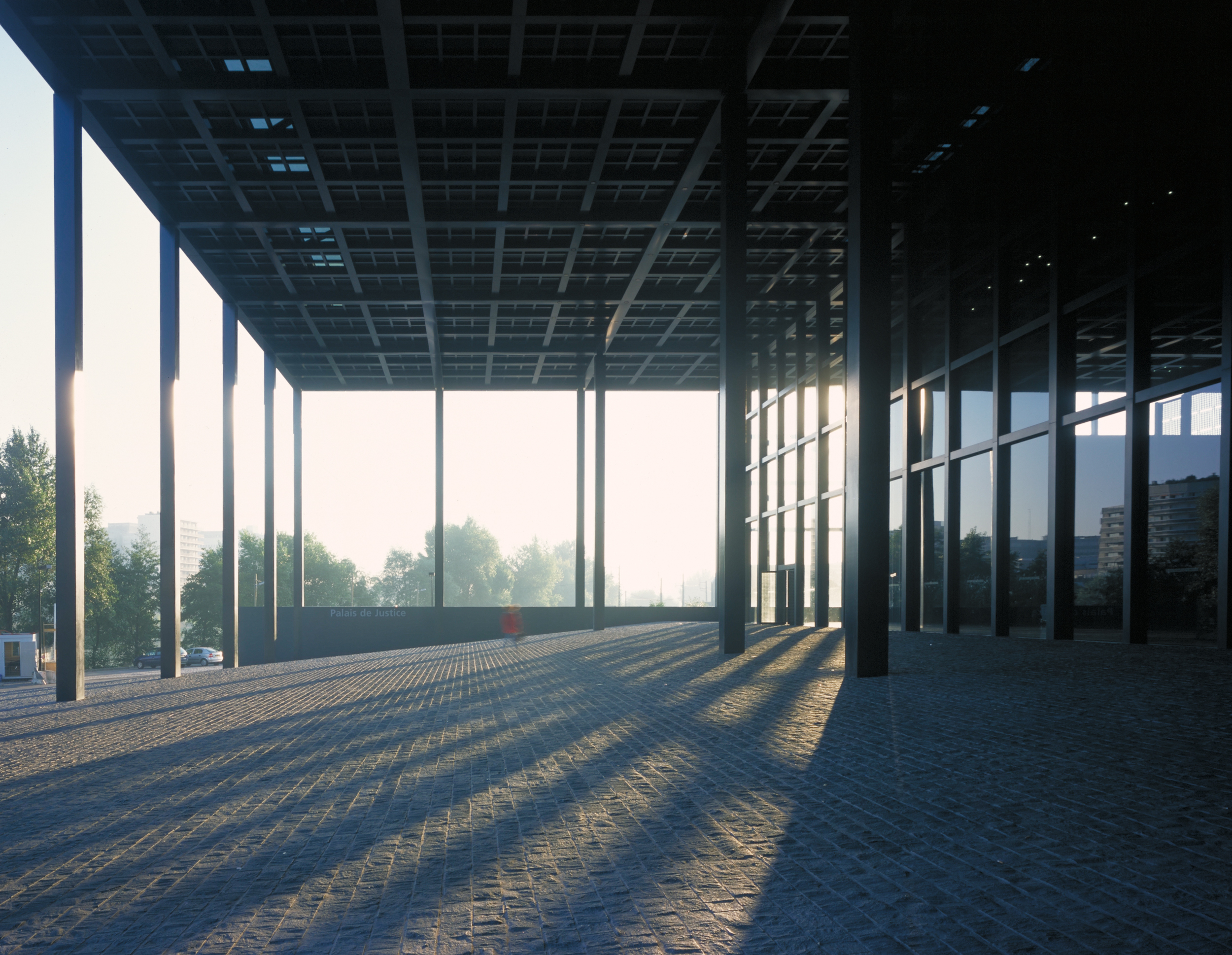

1993-2000, Ministry of Justice, Nantes, France, JEAN NOUVEL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1995-1999, Cognacq-Jay Foundation / Nursing home care, Rueil-Malmaison, France, JEAN NOUVEL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2011–2016, Neues Atelier, Haldenstein, Switzerland, PETER ZUMTHOR |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

GROPIUS, WALTER

JOHNSON, PHILIP

MIES VAN DER ROHE, LUDWIG

NOUVEL, JEAN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1851, Crystal Palace, London, UK, Joseph Paxton |

| |

|

| |

1937, Gropius House, LINCOLN, MASSACHUSETTS, USA, Walter Gropius |

| |

|

| |

1949, Glass House, New Canaan, USA, Philip Johnson |

| |

|

| |

1951, Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, USA, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe |

| |

|

| |

1962, Bell Laboratories, Holmdel, USA, EERO SAARINEN |

| |

|

| |

1993-2000, Ministry of Justice, Nantes, France, JEAN NOUVEL |

| |

|

| |

1995-1999, Cognacq-Jay Foundation / Nursing home care, Rueil-Malmaison, France, JEAN NOUVEL |

| |

|

| |

2011–2016, Neues Atelier, Haldenstein, Switzerland, PETER ZUMTHOR |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|