| ALL |

|

AMSTERDAM, NETHERLANDS

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Although not the seat of government, Amsterdam, in the province of North Holland, is the acknowledged capital (hoofdstad) of the Netherlands and, until World War II, was its architectural leader. Its local professional groups—Architectura et Amicitia, De 8, and Groep 32—were successively at the forefront of innovation, and despite the subsequent evaporation of regional hierarchies, the city has retained its prominence. Its inclusive and diversified buildings, especially those from the first third of the century as well as from its final decade, are endowed with a specifically local flavor, even when responding to more global design trends. Amsterdam’s watery foundations (many of the buildings rest on wooden pilings) and extensive network of canals and islands, no less than its distribution into distinctive quarters, ensure its unique character. Although 20th-century structures are interspersed among the picturesque remnants of the older city, the majority of these buildings were planted in an encircling girdle that extends dramatically but deliberately from the historic core. In Amsterdam, chronology and geography After the Golden Age of the 17th century, the cosmopolitan and prosperous harbor city became a somnolent town with a declining population until belated industrialization and the construction of international canals and railways commenced in the late 19th century and Amsterdam awoke to an expansive future, with concomitant woes (a desperate housing shortage, ruthless demolition, tactless road building, and the filling in of canals and open space) and wonders (prosperity generating provocative new construction). Thanks to the National Housing Act (Woningwet) of 1901, which required Dutch municipalities to provide extension plans and building codes (which in Amsterdam included aesthetic prescriptions), the city’s development proceeded responsibly. Initially, the main augmentations were southward, but eventually rings of buildings surrounded it in all directions. In the 1920s, Amsterdam was called the “Mecca of housing”; its social democratic administration insisted that dwellings answer artistic demands, serve the community, and embody the cultural aspirations of the working and lower-middle classes. Housing has continued to be the dominant building type.

Although at the turn of the century eclecticism ruled in Amsterdam as elsewhere, two contrasting yet complementary buildings signaled a fresh start. One was the vast Bourse (1897–1903) by H.P.Berlage, its sources in medieval architecture and the theories of Gottfried Semper and E.E.Viollet-le-Duc transformed by Berlage’s personal quest for a universal language suitable for all programs and viewers; the other was the American Hotel (1898–1902) by Willem Kromhout (1864–1940), a more playful design incorporating Byzantine and Arabic motifs as well as Romanesque. Both are unusually monumental for the time and place, with corner towers that anchor and announce their presence in the cityscape. Each is constructed from Amsterdam’s traditional material: unplastered brick (glowing red in a large “cloister” format for the Bourse, pale yellow and slender for the hotel) with stone trim kept within the sleek plane of the masonry walls. The elevations and plans obey a proportional system intended to harmonize the parts with the whole, characteristic of Amsterdam practice. Gifted applied artists executed the details and contributed to the interiors, which are representative of Nieuwe Kunst, the geometric and restrained Dutch version of Art Nouveau. A third building, the imposing polytonal masonry headquarters (1919–26) for the Dutch Trading Company (Nederlandsche Handelsmaatschappij, today ABN-Amro Bank), extended this aesthetic into the 1920s. The concrete-frame construction, rare at the time, was articulated by projecting vertical piers that unite five stories, an American formula seen previously only in the Scheepvaarthuis (1912–16; see Amsterdam School). Its theosophically inclined designer, K.P.C.de Bazel (1869–1923), one of the first Dutch architects to employ proportional systems, further interpreted his contemporaries’ goals in a personal manner in his housing projects for the municipality and the philanthropic organization De Arbeiderswoning.

Berlage was the author of the first modern extension, Amsterdam Zuid (South); in 1915, he exchanged his picturesque plan of 1905 for a more formal and practical layout to accommodate large-scale housing. The formula behind his acclaimed design, executed mainly between 1917 and 1927, was “in layout monumental, in detail picturesque” (Berlage quoted in Fraenkel, 1976, 46), meaning individualized and intimately scaled; discrete neighborhoods were composed of turbine plazas, winding streets, and perimeter blocks, often enclosing communal gardens, with the typical Amsterdam arrangement of floor-through dwellings ranged to either side of entries and stairs, creating a verticalcoalesce: for the most part, one can recognize the era of construction from the location. punctuation in the long facades. These smaller urban units were woven into a larger tapestry of avenues leading, in Berlage’s original vision, to major public structures. The latter were replaced by four-story multiple dwellings, but since these were designed mainly by the Amsterdam School, the grandeur, exuberance, and luxury associated with institutional buildings invigorate the housing and the accompanying schools, shops, communal bathhouses, branch libraries, bridges, electrical transformers, and so on that form an integral part of Amsterdam Zuid. A stylistic and typological anomaly in Plaz Zuid is the Wrightian Olympic Stadium (1926–28) by Jan Wils (1891–1972), who was briefly a member of De Stijl.

Other important districts created in the period during and immediately after World War I under the guidance of the dynamic director of housing Ary Keppler include the Spaarndammerbuurt north of the railroad tracks, best known for Michel de Klerk’s dwellings for the workers’ housing society, Eigen Haard (1915–20), but with interesting ensembles for other such organizations established by union members with government support, most notably Zwanenhof (1915–20) by H.J.M.Walenkamp (1871–1933). On reclaimed land north of the IJ estuary (Amsterdam Noord), a series of garden suburbs with more conventional two-story row housing offered an alternative to the denser matrix of Amsterdam Zuid. A significant municipal experiment of 1921 was Betondorp in Watergraafsmeer, annexed by Amsterdam in that same year, where a number of different systems employing concrete for rapid and cheap construction were tested. Some 1,000 dwellings were added to the housing stock; some of the experiments provided useful precedents, while others proved but temporary expedients. Architects included those of Amsterdam School persuasion, such as Dirk Greiner (1891–1964) and Jan Gratama (1877–1947), and budding functional-ists, such as the Haarlem-based J.B.van Loghem (1881–1940).

Amsterdam’s belt of new extensions, with buildings firmly defining streets and squares, was scornfully decried as the “stone city” by a younger generation touched by the ideas of Le Corbusier, the Bauhaus, and CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne). In 1927 these polemicists founded De 8 and issued a manifesto denouncing the putatively antiutilitarian and defiantly aesthetic schemes then dominant and demanding the introduction of Zakelijkheid (Nieuwe Bouwen in the Nether-lands). The most distinguished examples of this tendency in Amsterdam comprise the school and cinema by Johannes Duiker; the glazed Apollohal (Apollolaan, 1933–35) by A.Boeken (1891–1951), a founder of Groep 32; the steel-framed, unplastered brick atelier dwellings with artists’ studios combining single- and double-height spaces (Zomerdijkstraat, 1934) by P. Zanstra (1905-), K.L.Sijmons, and J.H.L.Giesen; and the strikingly transparent “Drive-In Dwellings” with garages below (Anthonie van Dijkstraat, 1936–37) by Mart Stam, Lotte StamBeese (1903-), W.van Tijen (1894–1974), and H.A.Maaskant (1907– 77). Buildings that also display modern materials and functionalist concepts but that, while devoid of Amsterdam School decorative flourishes, have a distinctly local rather than international character include the brick “Wolkenkrabber” (Amsterdam’s first “Skyscraper”; Victorieplein, 1930), its glazed stair separating the two apartments on each floor designed by an apostate from the Amsterdam School, J.F.Staal (1879–1940), and the curvaceous white National Insurance Bank (Apollolaan, 1937–39) by Dirk Roosenburg (1887–1962).

De 8 had published proposals to replace perimeter blocks with Germanic open-row housing and four-story tiers of dwellings with high, horizontally layered flats accessed by galleries or corridors and served by a single stair or elevator. When Cornelis van Eesteren designed the AUP (Algemene Uitbreidungsplan [General Extension Plan]) of 1934, he likewise envisaged tall slabs standing free in parklike settings and, according to CIAM prescriptions, segregated the city according to use: dwelling, working, recreation, and transport. Although World War II prevented complete realization, his scheme guided development until the late 1980s: Bos en Lommer (1937 and later, by De 8 members Ben Merkelbach [1901–61] and Ch. Karsten [1904–79]) and Frankendael (1947–51, by Merkelbach and Karsten and Merkelbach and P.Eilling [1897–1962] with Mart Stam) are examples of such worthy but architecturally undistinguished solutions.

In the postwar period, only on occasion did modernists escape tired formulas. The curtain wall appeared first in 1959 in the unusually elegant Geillustreerde Pers (Illustrated Press) headquarters by Merkelbach and Stam. Reconstruction focused on social housing, and the strict economic guidelines enforced by a government bureaucracy led to monotony and mediocrity. The culmination of CIAM thinking was the enormous southeastern housing estate Bijlmermeer (1962–73), designed by the Municipal Housing Service. This dispiriting honeycomb of concrete high-rises was linked to the center by the Metro, a remarkable feat of engineering of the 1970s that unfortunately did far more damage to Amsterdam’s fabric than the Nazi occupation. The precepts that produced Bijlmermeer were finally repudiated in the scheme by OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture, led by Rem Koolhaas) for the Ijplein in Amsterdam Noord (1980–82). Like Berlage’s Amsterdam Zuid, variety was naturally achieved by employing different firms to execute the plan, which consists of tall blocks in the western sector and low-rise buildings in the east, producing a successful mix of housing types conforming to OMA’s neomodernist stance.

By the 1960s, editors of the journal Forum urged reform. Aldo van Eyck (1918–99) criticized the sociologically driven soulless modernism that had blighted his country, called for “labyrinthine clarity” (ordered and logical complexity), proposed theories that drew inspiration from the African Dogon and the Casbah, emphasized the importance of intimacy and the thresholds between public and private space, and envisaged the city as a large house and the house as a small city, thus challenging Amsterdam’s inert and self- contained enclaves. After designing many ingenious playgrounds throughout the city, he realized his ideals in the acclaimed but flawed Burgerweeshuis (City Orphanage, 1960, no longer used as such), a miniature townscape of domed units of concrete and brick scaled to its small inhabitants. A subsequent movement, Structuralism, was formed by sympathizers such as Herman Hertzberger (1932-), whose Le Corbusian Studentenhuis (Student Dormitory, 1959–66), which combines social and dining facilities with living quarters and a common terrace (a street in the sky), exemplifies this approach; within the compound, a matrix of large and small rooms offers points where social encounters, often accidental, can enrich daily life.

Since the mid-1980s, there has been an explosion of exciting new architecture in Amsterdam, comparable in magnitude and inventiveness to the period between 1915 and 1934. Postmodernism is alien to Amsterdam, although the neo-Expressionist, ecologically prescient “sand castle” that houses the NMB (today ING) bank (1979–87) by A. (Ton) Alberts (1927–1999) and M.van Huut might be categorized as such, in that Alberts has revived the anthroposophical organicism of the early 20th century. Instead, an exuberant, triumphantly contemporary and quintessentially Dutch architecture has reappeared. Housing projects are again a cause for celebration, no longer constrained by politically correct but architecturally lifeless requirements. Redeveloped sites such as Kattenburg and Wittenburg (post office and flats by A.W.van Herk and S.E.de Kleijn, 1984) and KNSM-, Java-, and Borneo-Eilanden (the harbor’s decline left the islands free for other uses) display housing less indebted to modernist dogma and more to vernacular and Amsterdam School sources, although Nieuwe Bouwen is not forgotten (towers and slabs by Wiel Arets [1955-], J.Coenen [1949-], and Sjoerd Soeters [1947-], among others, 1988–96). Clusters of colorful and individualistic apartment blocks by firms such as Atelier Pro (who inclusively invited six foreign firms to provide facades for their housing development on the site of a former Army Barracks on the Alexanderkade, 1988–92) and Mecanoo (housing estate Haagseweg, 1988–92) reinvigorate the city and reinforce the identity of particular places. There has been a return to four- or five-story buildings organized according to the traditional Amsterdam entry system (Nova Zemblastraat by Girod and Groeneveld, 1977), each with its own distinctive details and massing, vigorously plastic with dramatic projections in plan and elevation. Wood and aluminum, as well as steel and stucco, often brightly painted, have joined brick, tile, and concrete as popular materials. Equally significant is the reconfiguration of older buildings— warehouses, arsenals, grain silos, customs houses, churches, and canal residences—for new purposes, again mostly residential; effectively active here is J.van Stigt (1934-). Amsterdam thus completed the century as it began: simultaneously socially responsible and architecturally on the cutting edge.

HELEN SEARING

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

1460, Begijnhof 34, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1550, Huiszittenmeesters, Oudezijds Voorburgwal 300, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Pakhuis Oudezijds |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1600, Vergulde Dolphijn, Singel 140-142, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Hendrick de Keyser |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1605, Burcht van Leiden, Oudezijds Voorburgwal 14, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1610, Huis op de drie Grachten, Oudezijds Voorburgwal 249/Grimburgwal/OudezijdsAchterburgwal, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Claes Adriaensz |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1615, Coningh van Denemarken, Herengracht 120, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1622, Huis met de Hoofden, Keizersgracht 123, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Pieter de Keyser |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1648, Stadhuis van Amsterdam, Dam, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Jacob van Campen |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1652, Singel 83-85, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Veerhuis De Zwaan |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1721-1731, Grill's Hofje, 1e Weteringdwarsstraat 11 -43, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1790, Singel 145, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1881, Krijtberg, Singel 446-448, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, A. Tepe

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1885-1887, St. Nicolaas, Prins Hendrikkade 76, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS,

A.C. Bleys |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

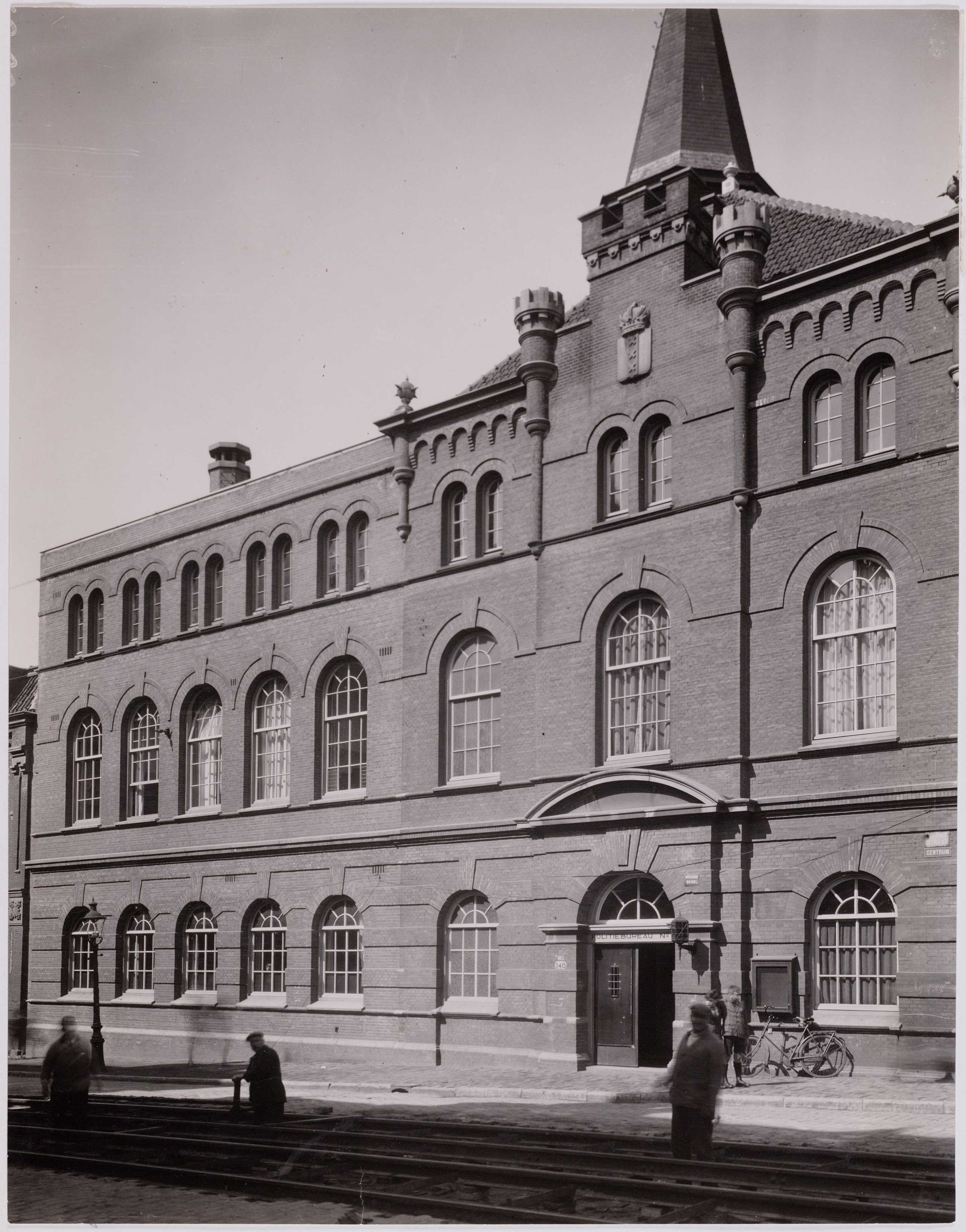

1888,Politiebureau Raampoort, Marnixstraat 148, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, B. de Greef

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1895-1899, Hoofdpostkantoor, Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal 182, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, C.H. Peters |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

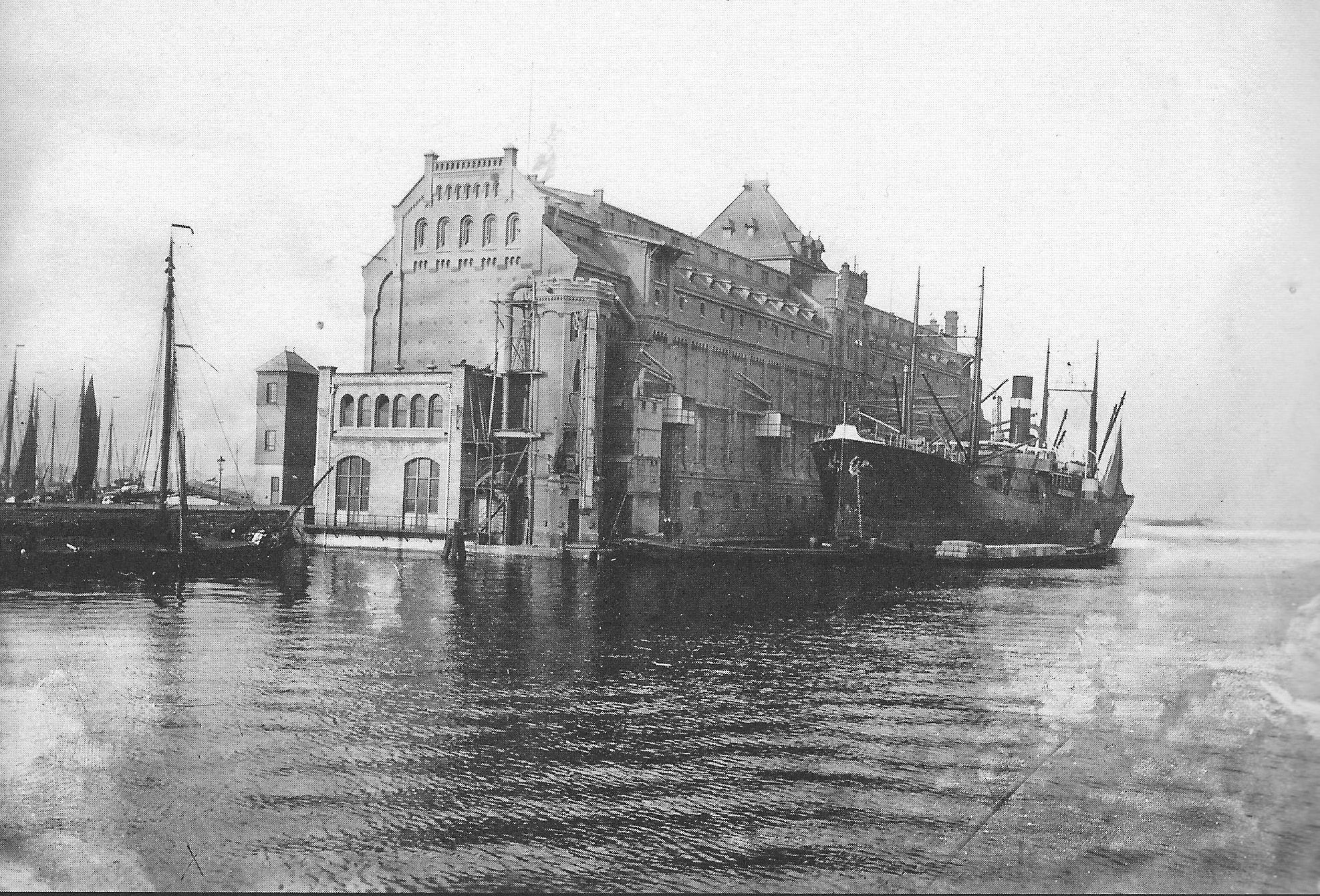

1896, Grain silo, Westerdoksdijk 52, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, J.F. Klinkhamer/A.L. van Gendt

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1898-1902, American Hotel, Leidseplein 28, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, W. Kromhout |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1898-1903, Koopmansbeurs, Beursplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, H.P. Berlage

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1913-1915, Eigen Haard, Spaarndammerplantsoen, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917-1920, Postkantoor, Zaanstraat/Oostzaanstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917-1920, Hembrugstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1919-1926, Nederlandse Handelsmaatschappij/ABN, Vijzelstraat 30-34, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, K.P .C. de Bazel |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1920, Insulindeweg/Celebesstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, H.Th. Wijdeveld |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921-1922, Dageraad, P .L. Takstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, P.L. Kramei |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921-1923, Henriëtte Ronnerplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1922-1927, Huize Lydia, Roelof Hartplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, J. Boterenbrood |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1929-1930, Openluchtschool, Cliostraat 36-40, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, J. Duiker |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1929-1930, De Wolkenkrabber, Victoriepleir, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, J .F Staal |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1937-1939, Social Verzekerings-bank, Apollolaan 15, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, D. Roosenburg |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1963, School, De Cuserstraat 3, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M.F. Duintjer

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1967, flats, Van Nijenrodeweg, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, W.M. Dudok

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1970, Dijkgraafplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, J .P. Kloos |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1973, Vrije Universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Architectengroep'69 |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1979, Kantoorvilla's, Weteringschans 26-28, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, F.J. van Gool

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1992, Wagons Lits office building, Ibis hotel, and bridge, Stationsplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Benthem Crouwel Architekten |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1993, Extension and alterations to Koninklijk Theater Carré, Amstel, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Onno Greiner Martien van Goor Architekten |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

ARCHITECTS: NETHERLANDS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

AMSTERDAM SCHOOL; ART NOUVEAU; DE STIJL; NETHERLANDS;

FUTHER READING

The bibliography in the Dutch language is huge but is specialized in terms of building types, time periods, and issues of urbanism and preservation; several items take the form of annotated guide books in Dutch and English. There is also a plethora of publications issued by the municipality, especially the Departments of Urban Planning (Stedebouw) and of Housing (Volkshuisvesting). Since 1986 ARCAM (Amsterdam Center for Architecture) has regularly commissioned a series of pocketbooks in English on various topics concerning the buildings of the city.

Amsterdam: Planning and Development, Amsterdam: Amsterdam Physical Planning Department, 1983

Bock, Manfred, Jet Collee, and Hester Coucke, H.P.Berlage in Amsterdam, edited by Martin Kloos, Amsterdam:

Architectura and Natura, 1992

Forgeur, Brigitte, Living in Amsterdam, London: Thames and Hudson, 1992

Fraenkel, Francis Frederik, Het Plan Amsterdam-Zu id van H.P. Berlage, Alphen aan den Rijn, The Netherlands: Canaletto, 1976 (with English summary)

Gemeentelijke Dienst Volkshuisvesting, Amsterdam/wonen, 1900–1975, Amsterdam: Bureau Voorlichting Gemeente Amsterdam, 1975

Groenendijk, Paul, and Piet Vollaard, Gids voor moderne architectuur in Nederland ; Guide to Modern Architecture in the Netherlands (bilingual English and Dutch edition), Rotterdam: Uitgeverij 010, 1986; 4th edition, 1992

Haagsma, Ids, and Hilde de Haan, Anna de Haas, H.J.Schoo, Amsterdamse Gebouwen, 1880–1980, Utrecht: Spectrum, 1981

Het Nieuwe Bouwen, Amsterdam, 1920–1960 (exhib. cat.), Delft: Delft University Press, and Amsterdam: Stedilijk Museum, 1983

Huisman, Jaap, Michel Clans, Jan Derwig, and Ger van der Vlugt, 100 jaar bouwkuns t in Ams terdam, Amsterdam: Architectura en Natura, 1999

Kemme, Guus (editor), Amsterdam Architecture: A Guide, Amsterdam: Thoth, 1987; 4th edition, 1996

Kloos, Maarten (editor), Amsterdam Architecture, 1991–93, Amsterdam: Architectura en Natura, 1994

Kloos, Maarten (editor), Amsterdam’s High-Rise: Considerations, Problems, and Realizations, Amsterdam: Architectura en Natura, 1995

Kloos, Maarten (editor), Amsterdam Architecture, 1994–96, Amsterdam: Architectura en Natura, 1997

Kloos, Maarten, and Marhes Buurman (editors), Amsterdam Architecture 1997–1999, Amsterdam: Architectura en Natura, 2000

Kloos, Maarten, and Yvonne de Korte(editor), Ring A10, Architectura & Natura Press, 2010

Koster, Egbert, Oos telijk Havengebied Amsterdam; Eastern Docklands , Amsterdam: Architectura en Natura, 1995

Paulen, Françoise (editor), Sociale woningbouw Amsterdam atlas ; The Amsterdam Social Housing Atlas (bilingual Dutch-English edition), Amsterdam: Amstaerdamse

Feratie van Woningcorporaties, 1992

Roy van Zuydewijn, H.J.F.de, Amsterdams e bouwkunst, 1815–1940, Amsterdam: De Bussy, 1969

Searing, Helen, “Architecture and the Public Works in Metropolitan Amsterdam,” Modulus 17 (1984)

Searing, Helen, “Betondorp: Amsterdam’s Concrete Garden Suburb,” Assemblage 3 (July 1987)

Stieber, Nancy, Housing Design and Society in Amsterdam: Reconfiguring Urban Order and Identity, 1900–1920, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998 |

| |

|

|