| ALL |

|

SUPERMODERNISM

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Critic and historian Hans Ibelings—borrowing from anthropologist Marc Augé—uses the term “supermodernism” (also called “hypermodernism”) to describe a style of architecture emerging in the 1990s, characterized by structures that are often airy, minimalist or monolithic, and transparent or translucent and that use an abundance of glass. Although supermodern structures exploit technological innovation, they are generally visually and symbolically simple, with clean lines, a minimalist style, and neutral materials.

Theoretically, Ibelings situates supermodernism in relation to Postmodernism and Deconstructivism and in conjunction with some of the aims of modernism. Ibelings noticed common tendencies in several architectural books published in the mid-1990s: Terence Riley’s Light Construction (1995), Rodolfo Machado and Rodolphe el-Khoury’s Monolithic Architecture (1995), Vittorio Savi and Josep Ma Montaner’s Less Is More: Minimalism in Architecture and the Other Arts (1996), and Daniela Colfrancescchi’s Architettura in superfice; Materiali, figure e technologie delle nuove facciate urbane (1995). The almost simultaneous publication of these texts describing a similar aesthetic led Ibelings to condense formal and theoretical tendencies into a description of a coherent architectural style.

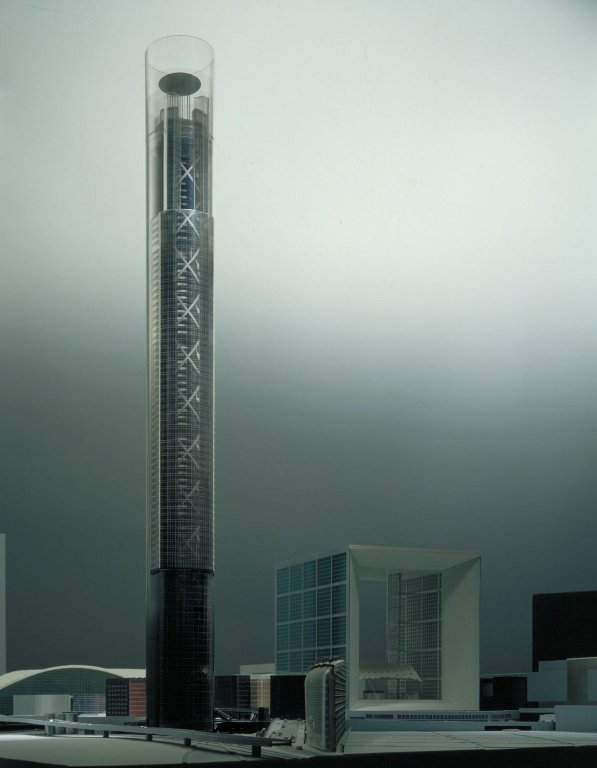

Contributors to this style include contemporary international architectural firms such as Rem Koolhaas’s Office of Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), Jean Nouvel, Dominique Perrault, Herzog and De Meuron, and Iñaki Abelos and Juan Herreros. Noteworthy examples of supermodernist architecture include Jean Nouvel’s beautifully transparent Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art and Head Office of Cartier France (1991–94) in Paris as well as his design for the Tour sans Fin (1989), a glass-topped tower to be built in Paris’s La Défense. Also significant are Dominque Perrault’s new home for the Bibliothèque Nationale (1989–96) in Paris as well as her Hotel Industriel Berlier (1985– 90) in Paris and Koolhaas and OMA’s Educatorium (1997), a multipurpose building designed for Utrecht University in the Netherlands.

Supermodernism is a phenomenological architecture, an architecture that appeals to the experience of place rather than to ideas or symbols. Although postmodernist and deconstructivist approaches to architecture often appeal to intellectual and historical relationships among forms, supermodernism suggested a shift toward (perhaps even a return to) the formal qualities of space and the visual and tactile sensations that accompany them. According to Ibelings, the emphasis on space and place rather than on form (or style as an end it itself) contradicts one of the main tenets of postmodern architecture—that a particular building is an often-contradictory composite of symbols or signs that carry cultural and linguistic meanings. Supermodern architecture rejects the desire or need to decode symbols and instead appeals to a range of physical as well as psychological qualities perceived through the experience of the forms. Supermodern buildings reflect neither the history of architecture nor extraarchitectural ideas.

The supermodern structure in part appeals to universal concerns (a stronghold of modernist ideology of the earlier part of the century). This emphasis on universality reflects the current interest in globalization, which Ibelings links to homogenization and commodification in art and architecture. Global homogenization has generated a rash of chain stores, internationally recognized products, and expressionless, nondescript architecture in world cities that resemble one another as well as architecture that is no longer built by local architects in local styles.

Linked to globalization is the development of what Augé calls “nonspace.” Nonspaces are spaces that “cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity” (Augé, 1995). Rather than social centers where communities gather for collective activity, nonspaces function as common places where groups of people come together yet experience the space separate from others. The current built environment is, according to Augé's somewhat relativist reading, meaningless. However, meaningless space arises as a reaction to three kinds of abundance: an abundance of space, an abundance of signs, and an abundance of individualism. The plethora of nonspaces creates what Augé calls the supermodern condition, an obvious reference to French philosopher Jean-Francois Lyotard’s 1979 seminal study La condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir (The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge).

Because globalization has increased world travel to a phenomenal extent, the airport perhaps functions as the quintessential nonplace, although supermarkets, hotels, and oversized malls could be added to this list. Ibelings argues that the airport structure has evolved into a universal type he describes as “an exposed steel construction (a space-frame or gigantic trusses), a marked preference for vaulted roofs, a colour palette of grey, white, pale blue and light green and, above all, acres and acres of glass” (1998). Examples of this design include Kansai International Airport Terminal, Osaka (Renzo Piano Building Workshop, 1988–1994); Hong Kong International Airport, Hong Kong, Chek Lap Kok (Foster and Partners, 1992–98); Stansted Airport, Essex, England (Foster and Partners, 1981–91); and Europier, Heathrow Airport, London (Richard Rogers Partnership, 1992–95). Functionally, the contemporary airport encompasses services such as shopping in addition to a means of travel, and further serves as an economic center for the surrounding area, a trend that reflects the transition of the symbolic city center to the periphery.

Supermodernism maintains particular traditions of modernism; namely, an aesthetic of neutrality, minimalism, and abstraction. Yet supermodernist architects seek expressivity; buildings are intended to be as autonomous and obviously separate from their surroundings; as contemporary and new, reflecting the present; as technically innovative; and finally, as a clean slate, an intended break from the past. Nonetheless, contemporary critics and stress the need to not only examine these qualities but to locate them within our contemporary global experience.

LINDA M. STEER

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.3 (P-Z). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1981–1991, Stansted Airport, Essex, UK, Foster and Partners |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1985-1990, Hotel Industriel Berlier, Paris, FRANCE, Dominque Perrault |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1988–1994, Kansai International Airport Terminal, Osaka, JAPAN, Renzo Piano |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1989, the Tour sans Fin, Paris, FRANCE, Jean Nouvel |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1989-1996, the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, FRANCE, Dominque Perrault |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1991-1994, Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art and Head Office of Cartier France, Paris, FRANCE, Jean Nouvel |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1992–1998, Hong Kong International Airport, Hong Kong, Chek Lap Kok, Foster and Partners |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1992–1995, Heathrow Airport, London, UK, Richard Rogers Partnership |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1997, OMA’s Educatorium for Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands, Rem Koolhaas |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

FOSTER, NORMAN

HERZOG AND DE MEURON

KOOLHAAS, REM

NOUVEL, JEAN

PIANO, RENZO

ROGERS, RICHARD |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1981–1991, Stansted Airport, Essex, UK, Foster and Partners

1985-1990, Hotel Industriel Berlier, Paris, FRANCE, Dominque Perrault

1988–1994, Kansai International Airport Terminal, Osaka, JAPAN, Renzo Piano

1989, the Tour sans Fin, Paris, FRANCE, Jean Nouvel

1989-1996, the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, FRANCE, Dominque Perrault

1991-1994, Cartier Foundation for Contemporary Art and Head Office of Cartier France, Paris, FRANCE, Jean Nouvel

1992–1995, Heathrow Airport, London, UK, Richard Rogers Partnership

1992–1998, Hong Kong International Airport, Hong Kong, Chek Lap Kok, Foster and Partners

1997, OMA’s Educatorium for Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands, Rem Koolhaas |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

Foster, Norman (England); Herzog, Jacques, and Pierre de Meuron (Switzerland); Hong Kong International Airport, Hong Kong; Kansai International Airport Terminal, Osaka; Koolhaas, Rem (Netherlands); Nouvel, Jean (France); Piano, Renzo (Italy); Postmodernism; Rogers, Richard (England)

FURTHER READING

Augé, Marc, Non-lieux: Introduction a une anthropologie de la surmodernité, Paris: Seuil, 1992; as Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity, translated by John Howe, London and New York: Verso, 1995

Ibelings, Hans, Supermodernism: Architecture in the Age of Globalization, Rotterdam: NAi, 1998

Lyotard, Jean-Francois, La condition postmoderne: rapport sur le savoir, Paris: Éditions de Minuit, 1979; translated by Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi as The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1984

Machado, Rodolfo, and Rodolphe el-Khoury (editors), Monolithic Architecture, Munich and New York: Prestel, 1995

Riley, Terence, Light Construction (exhib. cat.), New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1995

Savi, Vittorio, and Josep M.Montaner, Less Is More: Minimalisme en arquitectura i d’altres arts; Minimalism in Architecture and the Other Arts (exhib. cat.; bilingual Catalan-English edition), Barcelona: Actar, 1996 |

| |

|

|