| ALL |

|

GERMANY

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

German architecture in the 20th century was forged by the

succession of political and social upheavals that swept through

Europe during the century, so often with Germany at their epicenter. Conservative and progressive, as well as regional and

international architectural tendencies battled for hegemony in

trying to shape the German built environment, each in their own

image. The result is a century of tremendously heterogeneous

architecture with seemingly few continuities or unifying themes.

Despite this diversity, a walk through many large German cities

today gives the impression that German architecture, perhaps

more than that of any other country in Europe, is an architecture

of the 20th century. Indeed, many consider Germany to be one

of the birthplaces, if not the home of modern architecture.

German architecture at the turn of the last century was characterized by continuation of many trends from the prosperous

decades immediately following German unification in 1871. In

architectural design, the use of extravagant historical styles flourished amidst increasing modernisation, particularly for the residences and commercial properties of the increasingly wealthy

upper and middle class. Alfred Messel's Wertheim Department

Store (1898-1908) in central Berlin, with it's mix of historicist

exterior details and unprecedented use of steel and glass in a

new building type celebrating the triumph of bourgeois, metropolitan consumer culture, epitomised this trend. The more nationalist and militarist tendencies of the German bourgeoisie

were embodied in Bruno Schmicz's

gargantuan Volkerschlacht

denkmal outside of Leipzig (1898-1913), celebrating the centenary of the Prussian victory over Napoleon.

The first sparks of a modern, non-historicist architecture

came from the Secession and Art Nouveau inspired reforms

against the conservative norm in Germany. The artist's colony

on the Mathildenhöhe in Darmstadt patronised by the Grand

Duke Ernst Ludwig of Hesse (1900-1908) and the Folkwang

buildings and artist community in Hagen promoted by Karl

Ernst Osthaus (1898- 1912) both experimented with new forms.

Houses and complete interior fittings in these communities by

Peter Behrens, the Viennese Secession architect Joseph Maria

Olbrich, and the Belgian designer Henri Van de Velde revealed

to the public a fresh, anti-historicist sense of form and ornament.

There was desire to escape history and dry academicism in

favour of a more realistic unification of art, design, life, and the

everyday world.

Such brief forays into the Art Nouveau (lugendstil) style at the turn of the century were soon subdued by : penchant for

more reserved, monumental, and often neo-classically inspired

forms that swept Germany in the years just before World War l.

Olbrich's Ties Department Store in Düsseldorf (1906-1909),

Paul Bonatz's main train station in Stuttgart (1911 1928), and

Hermann Billing's Art Museum in Mannheim (1906-1907) are

typical of this often monumental trend in stone construction.

This general call for architectural order and regularity was

promoted by several reform institutions founded in the first

decade of the century. Among the most important were the

preservation oriented German Heimatschutz Bund (Homeland

Protection Association), founded in 1907, and the German Gar-

den Cities Association, founded in 1902, to promote the establishment of traditionally planned towns of suburbs with restrained, arts-and-crafts style architecture to contrast with the

increasingly unliveable industrial metropolis. The most well-

known reform organisation. however, was the Deutscher Werk-

bund, founded in 1907, intent on promoting a greater cooperation of German artists and industrialists with the explicit intent

of producing more modern consumer goods to increase German

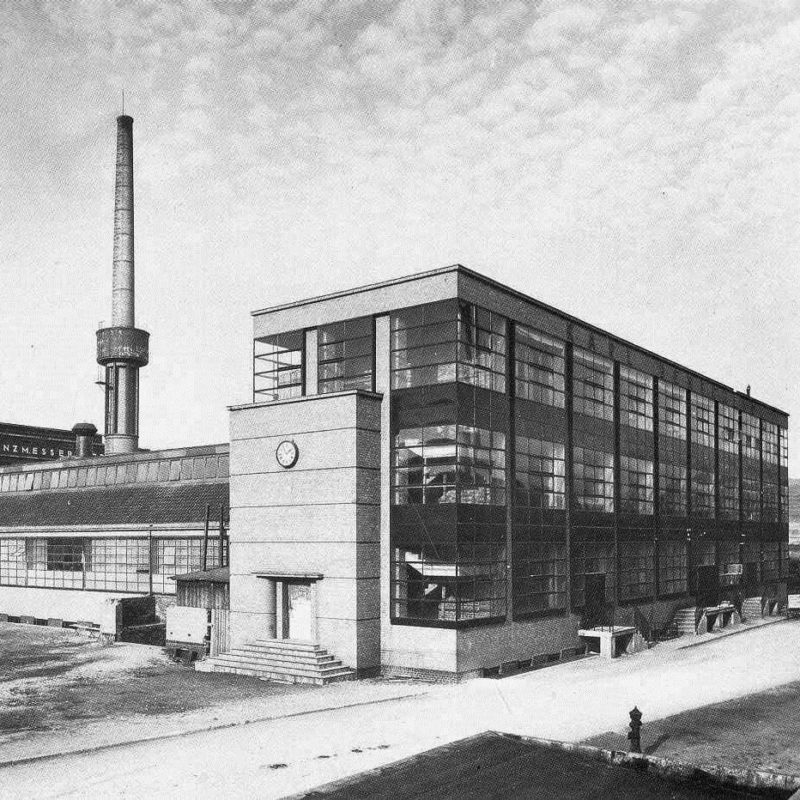

exports. Behrens' AEG Turbine Factory (1908-1909) and Walter Gropius' factories for the Fagus shoe last manufacturer

(1911-1914) and for the Cologne Werkbund exhibition (1914)

were typical Werkbund products as they expressed Germany's

new industrial image with a reserved, classically inspired set of

architectural forms.

World War brought Germany's defeat in November 1918,

and with it the end of empire, an unsuccessful communist revolution, the imposition of social democracy, as well as economically crippling war reparations payments imposed on Germany,

Although there was little work for architects, culture and architecture took on increasing ideological power in the attempt to

reform society in the new social democracy. In the wake of

defeat, groups of young artists and architects such as the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Working Council for Art) and the Novembergruppe, led by Gropius, Bruno Taut, Mics van der Rohe, and

others, dreamed up Expressionist, utopian architectural fantasies

that spoke of a revolution in architecture and a longing for :

new architectures of glass and steel, colour and purity. In 1919

state officials asked Gropius to unify Weimar's old art academy

and applied arts schools and create state-sponsored Bauhaus,

a school that unified all the arts under the leadership of architecure on the model of a medieval cathedral workshop. Although

it produced very few buildings, the Bauhaus proved to be one

of the most important forces in reforming and modernising

design and architectural thinking in Germany and throughout

Europe.

In the years immediately after the war, shortages of building

materials and spiralling inflation made most construction impossible. The overcrowded cites and pone housing conditions, a

legacy of Germany's rapid industrialisation, only grew worse.

Some of the more successful attempts to create housing focused

on do-it-yourself building, technology such as rammed-carth

construction and the small-scale Volkswehnung (People's

House), similar to those advocated by the Garden Cities Association. Many of the important commissions that were built after

the war, such as the Grosses Schauspielhans (Large Theater) in

Berlin by Hans Pockzig (1918-1919), the Einstein Tower in

Potsdam by Erich Mendelsohn (1920-1921), and the Chilehaus

by Fritz Höger in Hamburg (1922-1923), began to realise an

architecture that was free of academic norms and focused on

dynamic, expressive forms and a wide range of colourful materials.

This Expressionism was a short-lived but very prevalent style that

touched nearly all modern architects, but was rarely continued in

the late 1920s. However, the organic functionalism of Hugo

Haring and the ecclesiastical architecture of Domenikus Bohm

are clearly related in spirit and form.

By the mid-1920s, through the help of American foreign aid,

the German economy and building industry began to revive and

came into one of the most vibrant and culturally avant-garde

moments of 20th-century architecture, the so-called "Golden

Twenties," when Berlin was the cultural capital of Europe. Al-

though most construction in Germany continued regional traditions of the Heimail (homeland style) or the ornamental

traditions of earlier decades, an unornamented, flat-roofed, tech-

nonlogically oriented modern architecture, or Neues Basen (New

Building) coalesced in urban centres such as Berlin, Frankfurt

(Ernst May), and Dessau (Gropius, Hannes Meyer, and the Bauhaus), as well as Magdeburg (Bruno Taut), Celle (Onto Haeser),

Hamburg (Karl Schneider), Munich (Robert Vorhoelzer), and

Alrona (Gustav Oelsner). Progressive architects increasingly associated with new left-leaning social democratic policies that

sought technologically oriented renewal for the masses, while

many conservative architects chose to associate with right-wing

nationalist groups in favour of a pure German culture and architecture.

The most important endeavour which brought about the Neues

Bauen were the vast public housing projects made possible by

the Social Democratic municipal governments all over Germany:

over 135,000 new housing units in Berlin. 65,000 units in Ham-

burg, and 15,000 in Frankfurt alone. Under the guidance of

planners such as Martin Wagner and architects such as Taut,

cities like Berlin taxed extant landowners steeply, purchased huge

tracts of land, formed cooperative house-building associations

that modernised the production of building materials, standardised building elements, and streamlined the construction industry, They produced government owned and subsidised housing

of all types that allowed thousands of worker families to escape

the infamous rental barracks and slums for small but efficiently

planned apartment complexes with modern kitchens and other

facilities. These innovative housing developments, most designed in a remarkably uniform style that would soon be dubbed

the "International Style," drew almost universal international

acclaim from architects such as Le Corbusier, J.J.P. Oud, and

Philip Johnson. There was, however, increasingly harsh critique

from within Germany, as the local press labeled the new architecture "Bolshevik" or "Jewish" attack on German architectural

traditions and inappropriate for the German climate and culture.

When Hitler and his National Socialist regime took over

political control of Germany in January 1933, the modern styles

associated with social democracy were halted in favour of a mix

of conservative styles, including the pitched-roof cottage for domestic architecture, monumental classicism for the urban civic

centres, and a highly technical modern architecture for transportation and industrial facilities. Many of the most esteemed modern architects were forced to leave Germany because of their

Jewish heritage, while others such as May, Meyer, Taut, Gropius,

Mies van det Robe, Wagner, Ludwig Hilberseimer, and Marcel

Breuer voluntarily left in search of more favourable political and

architectural climates, especially in the United States.

Hitter took an intense personal interest in the development

of a Nazi architecture; he chose Paul Ludwig Troost and later

the young Albert Speer to oversee all major architectural production in the Third Reich. Speer

and his teams of architects re-

planned and even started construction in seven major representative regional cities to serve as parry headquarters, foremost

among them Berlin. The severe, bombastic classical style, solid

granite building, ensembles they envisioned were to evoke the

power, glory and longevity of the German Reich. World War

11 put halt to most of these projects, although large ensembles

remain in central Munich. namely the party grounds outside of

Nuremberg by Speer (1934-1939), in the Gauforum in Weimar

by Hermann Giesier (1936-1942), and in Berlin.

But the story of Nazi archirecture was more insidious and

pervasive than a few monumental projects. German architects

designed the concentration and extermination camps of the Holocaust for maximum efficiency. Slave labor from the camps was

used in quarries, brick furnaces, and many points of the building

industry, especially for the most representative architectural

projects. Architects also designed factories and entire industrial

towns for the machinery of war such as the cities of Salzgitter

for coal mining (Werner Hebebrand, 1937), and Wolfsburg for

Volkswagen (Peter Koller, 1938), as well as transport facilities

such as the Autobahn, and even vacation facilities for German

workers and soldiers such as the great beach facilities on the

island of Rügen (Clemens Klotz, 1935-1939). Thousands of

German architects of all persuasions joined the Nazi party in

order to keep their practices, and most continued their work

after the war, despite their Nazi affiliations.

The victorious Western Allied powers (under the leadership

of the United States' Marshall Pian) exercised strong control

over the redevelopment of Germany's post war economy, gowermment, society, culture, and architecture. Throughout Ger many, the immediate post-war years were dedicated to clearing

and recycling literally mountains of building-rubble from

bombed out cities- most of the work being done by women.

This was followed by rapid rebuilding of society's basic architectural needs, including hospitals, schools, temporary churches,

and above all housing, with peak production reaching 600,000

units/year.

Under the sway of Communist Russia, in East Germany, an early "National Building Tradition" was officially dictated by

Moscow in deliberate contrast to the "American" International

Style architecture in West. The references to Schinkel's classicism in the signature project of the Stalinalice(1952-1958) by

Hermann Henselmann in Berlin was an attempt to distill references from history and region into the representational and monumentalizing goals of the regime intent on differentiating itself

from both the Nazi past and the capitalist West. Over time, important historical monuments and historic city centres were restored with a care and expertise rarely seen in the West, as the best

of architectural heritage was made available to the working class.

Following, Stalin's death, Khrushchev ordered a complete

about-face towards rationalisation and standardisation, both out

of economic necessary as the cheapest way to build, but also to

symbolise the modernity of the East. After 1955 the entire build-

ing industry was systematically reorganised to churn out factory

prefabricated concrete apartment blocks both in and around

every East German city. Housing developments in Berlin's Marzahn, Jena, and Hoyerswerda were technologically more primitive and less comfortable than similar developments in the West

but represented a similar loss of urban and architectural quality

and an exclusive orientation to function and economics.

In West Germany, the "Economic Miracle" brought on by

reconstruction and the development of a capitalist, modern state

radically reshaped the face of nearly every city and town by the

1950s. Minimalist, abstract modern architecture became pervasive, especially in the larger, representational projects that commenced after the primary needs of society had been met. Egon

Fiermann's German Pavilion for the Brussels World's Fair of

1957 set the dominant tone for architecture that was to be trans-

parent and simple, modest and modern. Increasingly successful

German businesses chose to represent themselves with the image

of American corporate modernism, such as Fiermann's designs

for Neckermann (Frankfurt. 1958-1961), Olivetti (Frankfurt,

1968-1972), and IBM (Stuttgart, 1967-1972) and the refined

glass slabs of the Thysenhaus skyscraper in Düsseldorf (Hentrich & Petschnigg, 1957 -1960). Entire new suburban business

districts such as Hamburg's City Nord and Frankfurt's Niederrad were part of general loosening of the traditionally dense

core of German towns made possible by the emphasis on transportation and technology in planning and architecture.

A vast array of museums, cheaters, and entire new university

campuses built after the 1950s were visible symbols of the at-

tempt by West German social democracy to rebuild German

culture by heavily subsidising ants and education. The Ruhr

University in Bochum (Hentrich-Petschnigg, 1962-1967), and

the Free University in Berlin by the English designers Candilis.

Josic and Woods (1962-1973) were highly ordered megastruecures built with purely functional and economic considerations.

Mies van der Rohe's new National Gallery in West Berlin

(1961 -1968) and Philip Johnson's museum in Bielefeld (1963-

1968) reinforced a trend towards a minimalist, highly technical

and rectilinear, functionalist aesthetic.

As a counter-reaction to the strictures of this highly ordered,

rational architecture inspired by Mies and American modernism,

the Expressionist Hans Scharoun and others worked towards :

more organic, anti-monumental planning and architecture. The

freedom of the

open spaces of Berlin's Kulturforum, as well as

Scharoun's most well known architectural designs, the Berlin

Philharmonic and Chamber Music Halls (1956-1963. 1979-

1984) and the State Library (1967-1976), each display a highly

personal, expressive style based on curves and angled geometries.

Located near the Berlin Wall at the heart of the Iron Curtain,

they soon became symbols of Berlin's freedom, in opposition to

the communist regime in the East. Some of the most evocative

buildings by German architects after the war were churches and

memorials such as those by Rudolf Schwarz, Gottfried Bohm,

and Otto Bartning that provided simple but memorable spaces

for worship and remembrance, often with organic plans and

hope in the future represented by modern architecture. The

draped tensile structures by Frei Otto and Günther Behnisch

for the Olympic Stadium in Munich (1972) continued this alter-

native trend in German modernism, precursor to some of the

fragmented shapes of more recent postmodernist and deconstructivist architecture.

Housing, continued 10 be one of the

most pressing issues

facing German architects after World War 11. Although Ger-

mans moved increasingly into single-family houses in the last

five decades of the century, large-scale housing developments in

the modern style such as those developed by the Neue Heimat

housing agency still formed the dominant housing sype. The

Interbau Building Exhibition, built with the parricipation of 53

well-known architects from 13 nations in the Hamaviertel dis-

trier of West Berlin in 1957, was prototypical, replacing a dense

city section with loose array of modern high-rise, low-rise, and

single-family houses 4 in a park-like setting. In its wake came 3

largely successful though often maligned and short-lived trend

of developing mega-scale housing complexes such as the Neue

Var Siedlung for 30.000 residents outside of Bremen (Ernst

May, Bernhard Reichow, Alvar Aalto et al, 1957-1962). and

the Markisches Viertel for 60,000 in Berlin (Werner Durrmann,

Georg Heinrichs, Oswald Mathias Ungers, et al., 1962-1972).

By the early 1970s there began to be an increasing reaction

against the ascetic modernist planning ideas and architecture

that had come to dominate the German landscape. Architects

called for a more contextually sensitive and traditional approach

to city building and architecture, and a wave of museum building

throughout West Germany, including Hans Hollein's Abteiberg

Municipal Museum in Mönchengladbach (1972-1978), James

String's Staatsgalerie in Stuttgart (1977-1982), and O,M. Un-

gers German Architecture Museum in Frankfurt (1979-84),

demonstrated an overt connection to the past, traditions, and

postmodern variety. Rather than tearing down extant buildings,

preservation, restoration, additions, and even reconstruction be-

came increasingly popular alongside a more contextual approach

to architecture that coincided with post-modernism. Berlin's International Building Exposition (IBA, 1979-1987) sought tO

reclaim some of the more run-down districts of West Berlin

through program of careful urban repair, while new infill housing projects, often with architectural references to history, tradition, and region, signalled a return to the traditional urban closed

facade and block formation.

The collapse of the Soviet Union led to German unification

and the dismantling of the Berlin Wall. The unified government

invested heavily in the East and provided incentives for private

industry to rebuild the infrastructure, renovate housing and cultural buildings, and set up branch offices and corporate

head-quarters throughout the Eastern states. The capitol was returned

to Berlin, which soon became one of the biggest construction

sites in Europe and the world. Department stores on the Friedrichsstrasse by 1.M. Pei, Jean Nouvel, O.M. Ungers and others

returned the street in the East to its former status as the most

elegant shopping street in Germany,

Although Berlin continues to be Germany's dominant metropolis, the country's federal political structure gives large atttonomy to the States, and helps reinforce regional identity, pride,

and wealth distribution such that pockets of the newest, most

innovative architecture appear all over the newly unified Germany. The new bank towers blossoming in Frankfurt, the ex-

panding port

and business centers in Hamburg, the new State

Parliament in Dresden (Peter Kulka, 1991-94) and the innovative Leipzig Convention Center (Von Gerkan, Marg & Partners,

1995-98) all resulted from unification as well as the internationalization associated with Germany's powerful role in the new

European Union and general globalisation. Although German

architects, with a few noteworthy exceptions, have received comparatively few opportunities to build abroad, the ubiquity of

architectural competitions continues to make Germany more

open than perhaps any ocher country to foreign and young architects, and new ideas. At the close of the 20th century bold experiments in theory and deconstructionism, in planning ideas, in environmental sustainabiliry, as well as in all manner of technology

and building performance in Germany continued to stimulate

and inspire new developments all over the world that will help

define the architecture of the succeeding century.

KAI K. GUTSCHOW

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.2. Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

1910-1911, Fagus Factory, ALFELD AN DER LEINE, LOWER SAXONY, GERMANY, WALTER GROPIUS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1919-1921, Einstein Tower,Teltower Vorstadt, Germany, ERICH MENDELSOHN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925-1926, Bauhaus building in Dessau, DESSAU, GERMANY, WALTER GROPIUS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927, The Weissenhof Estate, Stuttgart, Germany, GROUP OF ARCHITECTS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928, Kaufhaus Schocken, Stuttgart, GERMANY, ERICH MENDELSOHN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1968, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1976-1979, Bauhaus Archiv-Museum, BERLIN, GERMANY, WALTER GROPIUS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1981-1985, IBA SOCIAL HOUSING, Berlin, Germany, PETER D. EISENMAN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1982, ABTEIBERG MUNICIPAL MUSEUM, MÖNCHENGLADBACH, GERMANY, HANS HOLLEIN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1995-1999, Municipal library, Dortmund, Germany, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1997, Red Dot Design Museum, Essen, Germany, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1998, Ludwig Erhard Haus, Berlin, Germany, NICHOLAS GRIMSHAW |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1999, Reichstag, New German Parliament, Berlin, Germany, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1999–2018, James-Simon-Galerie, Museum Island, Berlin, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2001, JEWISH MUSEUM BERLIN, Berlin, Germany, DANIEL LIBESKIND |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2001, Frankfurt Trade Fair Hall, Frankfurt, Germany, NICHOLAS GRIMSHAW |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2001-2005, BMW Central Building, Leipzig, GERMANY, ZAHA M. HADID |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2002-2005, Allianz Arena, München-Fröttmaning, Germany, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2005, Free University, Berlin, Germany, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2006-2016, Elbphilharmonie, Hamburg, Germany, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2007–2009, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2016-2021, MKM Museum Küppersmühle, Extension, Duisburg, Germany, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

ARCHITECTS: GERMANY |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1910-1911, Fagus Factory, ALFELD AN DER LEINE, LOWER SAXONY, GERMANY, WALTER GROPIUS |

| |

|

| |

1919-1921, Einstein Tower,Teltower Vorstadt, Germany, ERICH MENDELSOHN |

| |

|

| |

1925-1926, Bauhaus building in Dessau, DESSAU, GERMANY, WALTER GROPIUS |

| |

|

| |

1927, The Weissenhof Estate, Stuttgart, Germany, GROUP OF ARCHITECTS |

| |

|

| |

1928, Kaufhaus Schocken, Stuttgart, GERMANY, ERICH MENDELSOHN |

| |

|

| |

1968, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlin, Germany, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

1976-1979, Bauhaus Archiv-Museum, BERLIN, GERMANY, WALTER GROPIUS |

| |

|

| |

1981-1985, IBA SOCIAL HOUSING,

Berlin, Germany, PETER D. EISENMAN |

| |

|

| |

1982, ABTEIBERG MUNICIPAL MUSEUM, MÖNCHENGLADBACH, GERMANY, HANS HOLLEIN |

| |

|

| |

1995-1999, Municipal library, Dortmund, Germany, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1997, Red Dot Design Museum, Essen, Germany, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

1998, Ludwig Erhard Haus, Berlin, Germany, NICHOLAS GRIMSHAW |

| |

|

| |

1999, Reichstag, New German Parliament, Berlin, Germany, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

1999–2018, James-Simon-Galerie, Museum Island, Berlin, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2001, JEWISH MUSEUM BERLIN, Berlin, Germany, DANIEL LIBESKIND |

| |

|

| |

2001, Frankfurt Trade Fair Hall, Frankfurt, Germany, NICHOLAS GRIMSHAW |

| |

|

| |

2001-2005, BMW Central Building, Leipzig, GERMANY, ZAHA M. HADID |

| |

|

| |

2002-2005, Allianz Arena,

München-Fröttmaning, Germany, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

2005, Free University, Berlin, Germany, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

2006-2016, Elbphilharmonie,

Hamburg, Germany, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

2007–2009, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2016-2021, MKM Museum Küppersmühle, Extension,

Duisburg, Germany, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

GROPIUS, WALTER; MENDELSOHN, ERICH; MIES VAN DER ROHE, LUDWIG; POELZIG, HANS;

FURTHER READING

Although the developments of German 20th-century architecture are

summarized in every survey of modern archisecture, and the literature

on the subject is rich and growing rapidly, an authoritative comprehen-

sive survey of this complex and often difficult century has yet to be

written. Monographs exist on most of the major and minor architeces,

institutions and particular epochs, especially of the inter-war period.

Guidebooks, including Nerdinger's, as well as studies on individual

cities, specially Scheer's catalogue on Berlin, often provide the best

overview of architecture across the century, The three catalogue volumes

edited by Magnano Lampugnani (1992, 1994) and Schneider (1998)

accompanied major retrospective exhibits at the German Architecture

Museum and represent some of the best scholarship on German archi-

secure, especially from 1900-1950. The best introductions in English

to pre-WW11 architecture are Lane, Pommet and Zukowsky, while the

best surveys of the developments after the war in English are Marshall,

De Bruyn, and Schwart.

De Bruyn, Gerd. Contemporary Architecture in Germany, 1970-1996:

50 Buildings, edited by Inter Nationes, Berlin and Boston:

Birkhäuser, 1997

Durth, Werner, Deatiche Architekten: Biographiche Verflechtungen,

1900-1970, Brunswick, Germany: Views, 1986, new edition

2001

Durth, Werner, and Niels Guschow, Architektar and Stadtebau der

Finfeiger fahre, Bonn. West Germany: Deutsches

National komitee für Denkmalschutz, 1987

Durth, Werner, J8r Duwel, and Niels Gutschow, Stadichu und

Architektur in de D.D.R, Frankfurt and New York: Campus,

1998

Feldmever. Gerard G., Die neve deutsche Architekrur, Stuttgart:

Kohlhammer, 1993; as The New German Architecture, translated

by Mark Wilch, New York: Rizzoli, 1993

Hoffmann, Hubert, Gerd Hatje, and Karl Kaspar, Neve deunche

Architektur, Saungart: Hasje, 1956, as New German Architecture,

translated by H.J. Montague, New York: Pranger, and London:

Architectural Press, 1956

Huse, Norbert. Neses Banen: 1918 -1933: Moderne Archicktur in der

Weimarer Republik, Munich: Moos, 1975; 2nd edition, Berlin:

Emm, 1985

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen, German Architecture for a Mass

Audience, London and New York: Routledge, 2000

Jakot, Paul B. The Architecture of Oppression: The SS. Forced taber,

and the Nazi Monumental Building, Fennowy, London and New

York: Routledge, 2000

Lane. Barbara Miller. Archivectore and Politics in Germany. 1918-

1945, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press,

1968: 2nd edition 1985

Magnano Lampugnani. Vittorio and Romana Schneider (editors),

Moderne Architektur in Destschland 1900 bis 1950; Reform und

Tradition, Stuttgart: Hatje, 1992

Magnano Lampugnani, Vittorio and Romana Schneider (editors),

Moderne Architektur in Desschland 1990 bis 1950: Expression

und Neue Sachlichkeit, Stungar: Hare, 1994

Marschall, Werner and Ulrich Conrads. Neve deutsche Archisektur 2,

Stuttgart: Hatje, 1962: as Modern Architectre in Germany,

translated by James Palmes, London: Architectural Press, and as

Contemporary Architecture in Germany, New York: Praeger, 1962

Nerdinger, Winfried and Cornelias. Tafél, Conida all'erchitenura del

Novecento, Germania, Milans: Electa, 1996; as Archiectural Guide:

Germany: 20th Centwy, translated by Ingrid Taylor and Ralph

Stem, Basel, Switzerland, and Boson: Birkhauser, 1996

Pehnt, Wolfgang, German Architecture, 1960-70, Architectural Press, 1970

Pommer, Richard and Christian F. Ono, Weisenhef 1927 and the

Modern Movement in Architecture, Chicagos University of

Chicago Press, 1991

Posener, Julias, Berlin asf dem Wege zu ciney neven Archikaur: Das

Tritalter Wilhelmus If, Munich: Prestel, 1979

Schneider, Romana and Wilfried Wang (editors), Moderne

Architektur in Deusehland 1900 bis 2000: Mach und Monument,

Ostfildern-Ruit: Harje, 1998

Schreiber, Mathias (editor), Deutsche Architkeur wach 1945: Vierzig

Jahre Moderne in der Bunderepublik, Stuttgart: Deutsche

Verlags-Anstalt, 1986

Steckewch, Carl and Sabine Galicher (editors), Ideen, Orte,

Entwürfe: Architektar and Städeban in der Bundesrepublik

Deuschland/Ideas, Places, Projects. Architecture and Urin

Planning in the Federal Republic of Germany (bilingual English

and German text), translated by Larry Fisher, David Magee, and

Renate Vogel Berlin: Ernst, 1990

Weiss, Klaus-Dieter, Young German Archisects/Junge deutsche

Architekten and Archisektinen (bilingual English and German

text), Basel, Switzerland, and Boston: Birkhauser, 1998

Zukowsky, John (editor), The Maxy Faces of Modern Architecture:

Building in Germany between the Wars, Munich and New York:

Presel, 1994

German Architects: Biographical Entanglements 1900-1970

Architectural guide. Germany 20th century

New Directions in German Architecture

The New German Architecture |

| |

|

|