| ALL |

|

DECONSTRUCTIVISM

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Deconstructivism is a theoretical term that emerged within art, architecture, and the philosophical literature of the late 1980s and early 1990s. The movement refers mainly to an architectural language of displaced, distorted, angular forms, often set within conflicting geometries. With origins in the ideas of French philosopher Jacques Derrida (b. 1930), deconstructivism generated an iconoclastic style of the avant-garde whose principle architec tural exponents included Coop Himmelb(l)au , Zaha Hadid, Behnisch and Partners, Bernard Tschumi, Peter Eisenman, Morphosis, Rem Koolhaas, Daniel Libeskind, and Frank Gehry, among others.

Curiously, while these and other architects have continued to practice in a related formal language, the terms once used to describe their work have long since dropped out of usage. Deconstruction in the field of architecture owes its origins to two parallel events that took place in 1988. One was an exhibition titled “Deconstructivist Architecture” held at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City; the second was a conference titled “Deconstruction in Art and Architecture” held at the Tate Gallery in London. The different terms employed by the organizers to describe their respective events highlighted their differing trajectories.

The exhibition in New York—originally to be called “NeoConstructivist Architecture” with reference to a revival of the Russian stylistic movement from the early part of the 20th century—highlighted the formal language emerging in the work of a group of avant-garde architects, including several of those aforementioned. The event in London, meanwhile, stressed the connection to Derridian philosophy. Deconstruction emerged out of the poststructuralist tradition of literary theory, which, in opposition to structuralism, stressed the slippage and fluctuation of meaning that is always at work in the process of linguistic and cultural signification.

Derrida first used the term to refer to a mode of inquiry that sought to expose the paradoxes and value-laden hierarchies that exist within the discourse of Western metaphysics. Although deconstruction dismantles or analyses such concepts, it was never meant to be nihilistic, according to Derrida. Rather, it serves as an epistemological method of engagement with the world. Although Derrida once described the philosopher as a “would-be architect,” always searching for secure foundations on which to construct an argument, the links between the philosophical term and architecture are clearly metaphorical. Derrida’s sense of the word is a method and not a style.

The connection between Deconstruction and architecture stemmed largely from Bernard Tschumi’s use of Derrida’s ideas in his competition-winning 1983 design for the Parc de la Vilette in Paris. Tschumi proposed a nonhierarchical grid of dispersed pavilions instead of a more traditional building, echoing deconstruction’s own challenging of linguistic arrangements. Later, Derrida himself collaborated with Peter Eisenman in the design of a small section of the landscaping of the park, and he subsequently wrote a commentary on Tschumi’s project, reading the random play of forms as metaphors for the aleatory or contingent play of meaning in language.

Derrida significantly referred in this piece to the “architecture of architecture.” In other words, if thinking about architecture is itself already a social construct, one might conclude that what needs to be deconstructed are not the architectural forms themselves but rather the theoretical assumptions that lie behind the design of those forms.

In effect, there were two competing events claiming Deconstructivism as their own; it either referred to a purely stylistic phenomenon, or it referred to a broad intellectual shift that encompassed not only philosophy but all the visual arts. As Bernard Tschumi noted, “The multiple interpretations that multiple architects [have given] to deconstruction [have become] more multiple than deconstruction’s theory of multiple readings could ever have hoped.”

The Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition might have more suitably retained the term “Neo-Constructivism,” even if the architecture that had inspired the movement also included the work of Suprematist architects, such as Kazimir Malevich.

There is clear evidence of a revival of interest in these forms—stripped of their social and political connotations—within the formal experimentations during the 1980s at the Architectural Association in London by architects such as Zaha Hadid of Iraq. Certainly, as far as many architects were concerned, the connections with philosophy remained a side issue in what was essentially a stylistic movement that did much to break the stranglehold of the harsh rectilinearity of modernist architecture (derived from International Style, a movement incidentally also spurred by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, earlier in the century) but that nonetheless remained within the trajectory of modernism.

As such, the deconstructivist style in architecture relates to what art historian and critic Hal Foster has termed a postmodernism of resistance, or a rupture of formal invention or a moment of recuperation within a cyclical, historical process that leads to ever-new emergent expressions of modernisms. Derrida himself consistently refused to articulate what, if any, connection there was between his work and the architecture of the same name. Meanwhile, Tschumi conceded that although certain philosophical ideas that dismantled concepts had become remarkable conceptual tools, they “could not address the one thing that makes the work of architects ultimately different from the work of philosophers: materiality.”

As a result, the terms “deconstruction” and “deconstructivism” soon fell out of favor within the architectural literature. Yet, paradoxically, at almost the same moment the architectural language to which they referred began to enjoy popular support. With the construction, in particular, of Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, this once shockingly radical and irreverant approach to architecture emerged out of the shadows of the avant-garde to become a mainstream architectural movement sanctioned by the public.

NEIL LEACH

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2004. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

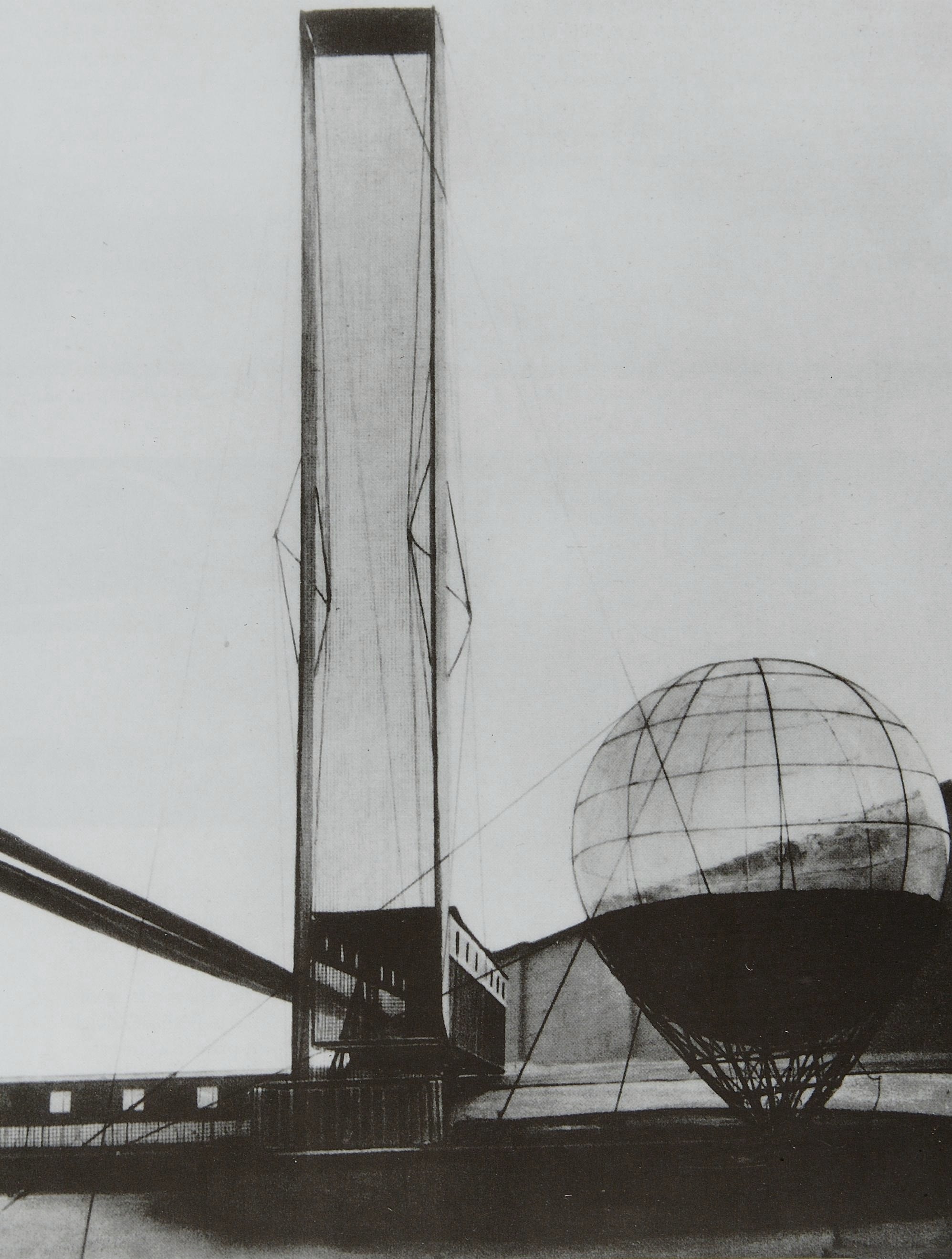

1927, LENIN INSTUTE, PROJECT, LEONIDOV, IVAN ILICH |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

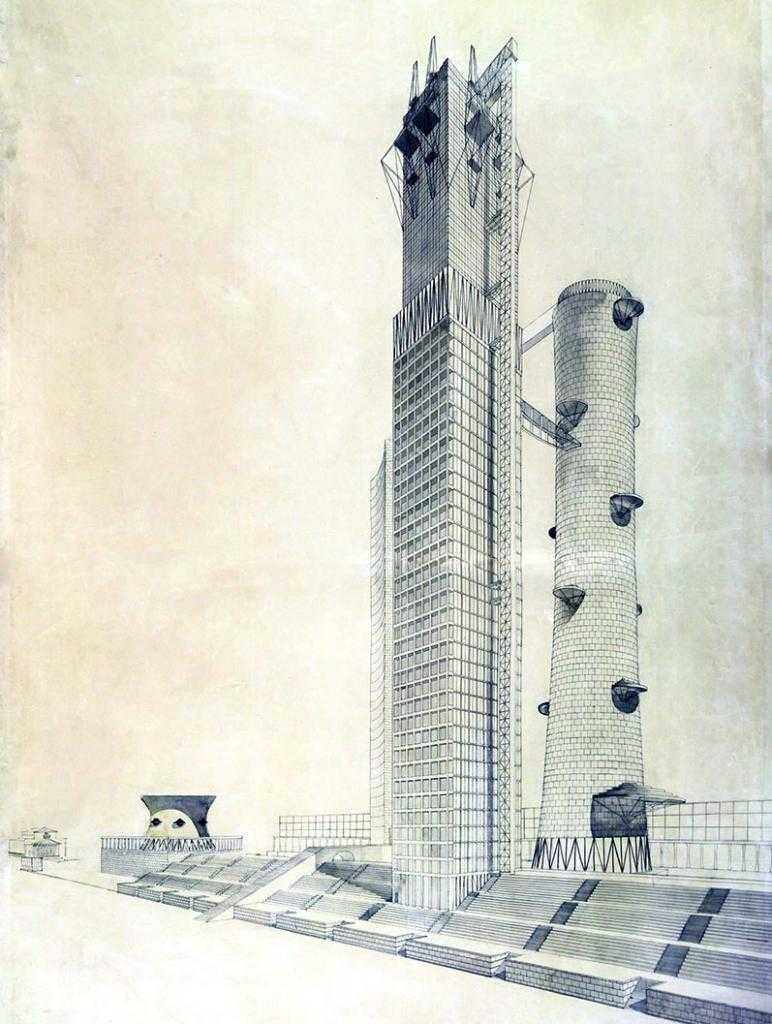

1934, NARKOMTYAZHPROM, PROJECT, LEONIDOV, IVAN ILICH |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1983, design for the Parc de la Vilette, Paris, FRANCE, Bernard Tschumi |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1983-1989, WEXNER CENTER FOR THE VISUAL ARTS AND FINE ARTS LIBRARY, Columbus, USA, EISENMAN, PETER D. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1985, Lucille Halsell Conservatory, San Antonio, Texas, USA, EMILIO AMBASZ |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1988-1996, ARONOFF CENTER FOR DESIGN AND ART, Cincinnati, USA, EISENMAN, PETER D. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1994, Vitra fire station, Weil am Rhein, GERMANY, ZAHA M. HADID |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1994, Vitra International Headquarters, Basel, Switzerland, FRANK OWEN GEHRY |

| |

|

| |

au.jpg) |

| |

1998, UFA Palast, Dresden, Germany , Coop Himmelb(l)au |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1999-2003, School of Architecture, FIU, Miami, USA, BERNARD TSCHUMI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2001, JEWISH MUSEUM BERLIN, Berlin, Germany, DANIEL LIBESKIND |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

AMBASZ, EMILIO

EISENMAN, PETER D.

GEHRY, FRANK OWEN

GINZBURG, MOISEI

HADID, ZAHA M.

KOOLHAAS, REM

LEONIDOV, IVAN ILICH

LIBESKIND, DANIEL

NOUVEL, JEAN

TSCHUMI, BERNARD |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1927, LENIN INSTUTE, PROJECT, LEONIDOV, IVAN ILICH |

| |

|

| |

1934, NARKOMTYAZHPROM, PROJECT, LEONIDOV, IVAN ILICH |

| |

|

| |

1983, design for the Parc de la Vilette, Paris, FRANCE, Bernard Tschumi |

| |

|

| |

1983-1989, WEXNER CENTER FOR THE VISUAL ARTS AND FINE ARTS LIBRARY, Columbus, USA, EISENMAN, PETER D. |

| |

|

| |

1985, Lucille Halsell Conservatory, San Antonio, Texas, USA, EMILIO AMBASZ |

| |

|

| |

1988-1996, ARONOFF CENTER FOR DESIGN AND ART, Cincinnati, USA, EISENMAN, PETER D. |

| |

|

| |

1994, Vitra fire station, Weil am Rhein, GERMANY, ZAHA M. HADID |

| |

|

| |

1994, Vitra International Headquarters, Basel, Switzerland, FRANK OWEN GEHRY |

| |

|

| |

1998, UFA Palast, Dresden, Germany , Coop Himmelb(l)au |

| |

|

| |

1999-2003, School of Architecture, FIU, Miami, USA, BERNARD TSCHUMI |

| |

|

| |

2001, JEWISH MUSEUM BERLIN, Berlin, Germany, DANIEL LIBESKIND |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

CONSTRUCTIVISM; Eisenman, Peter; Gehry, Frank ; Hadid, Zaha ; Koolhaas, Rem ; Libeskind, Daniel ; Nouvel, Jean; Postmodernism; Tschumi, Bernard

FURTHER READING

Derrida, Jacques, “Letter to Peter Eisenman,” Assemblage, 12 (August 1990)

Derrida, Jacques, “Point de folie—Maintenant l’architecture,” in Rethinking Architecture: A Reader in Cultural Theory, edited by Neil Leach, London and New York: Routledge, 1997

Derrida, Jacques, “Why Peter Eisenman Writes Such Good Books,” in Rethinking Architecture: A Reader in Cultural Theory, edited by Neil Leach, London and New York: Routledge, 1997

Johnson, Philip, and Mark Wigley, Deconstructivist Architecture: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Boston: Little Brown, 1988

Papadakis, Andreas, Catherine Cooke, and Andrew E.Benjamin (editors), Deconstruction: Omnibus Volume, New York: Rizzoli, and London: Academy Editions, 1989

Wigley, Mark, The Architecture of Deconstruction: Derrida’s Haunt, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1993 |

| |

|

|