| ALL |

|

METABOLISTS

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

The Metabolist movement emerged at the Tokyo meeting of the 1960 World Design Conference (an epilogue to the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne [CIAM, 1927-]), with the proposal that architecture should not only embrace new technologies and the enormous scales of the post-war period but also develop living, self-generating systems that could adapt over time. Founded by a group of ambitious young architects intent on challenging the status quo and thus establishing their own presence among the international congress of leading architects, the movement's core group included the architects Kiyonori Kikutake, Fumihiko Maki, and Kisho Kurokawa, all of whom later enjoyed enduring international reputations. In addition, another architect, Masato Otaka, the critic Noboru Kawazoe, the graphic designer Kiyoshi Awazu, and the industrial designer Kenji Ekuan were also involved in the production of the bilingual manifesto published by the group.

Although the Metabolists were a small group, Metabolism as a movement included others, especially Kenzo Tange and his assistant Takashi Asada, who nurtured the founders through a sort of late-night salon. Tange's "City for 10 Million People" (1960), to be built along a series of looped roadways stretching across Tokyo Bay, was a direct response to his proteges' work. Arata Isozaki, working for Tange during the same period, was also identified with the movement, but he took a darker view, reflected in his sketches of brutal concrete towers rising from ruins.

The original Metabolists' relative lack of professional experience was reflected in their audaciously futuristic proposals. In the group's only publication, Metabolism 1960: The Proposals for New Urbanism, Kikutake's sketches were particularly prominent, taking up over a third of the original text; his 1958 Sky House was the only built work included. Kikutake offered up sail-shaped cities floating on ferro-cement hulls, "plug-in" housing tacked on to soaring towers by magnets, light fixtures freely connected to electrified steel walls, and commutes by submarine or helicopter. The Metabolists are often accused of lacking the sense of improbable delight found in the slightly later Archigram's works, but Kikutake's original essay shows the same wobbly, giddy thinking. Unfortunately, his essays' English translations are clunky and difficult to comprehend, and the humor he brought to the movement was poorly recognized abroad, replaced by dry restatements of the Metabolists' positions.

Although the group established an apparently united front, the founders held a diverse set of theoretic concerns that prevented them from advancing as a movement after their debut. Maki and Otaka were not concerned with a new technological framework or production issues but rather with understanding and incorporating traditional spatial patterns into designs for the unprecedented scale of the new city. For Kurokawa, Metabolism began as an organizing device, emphasizing structure, which allowed him to build some of its most successful buildings a decade later.

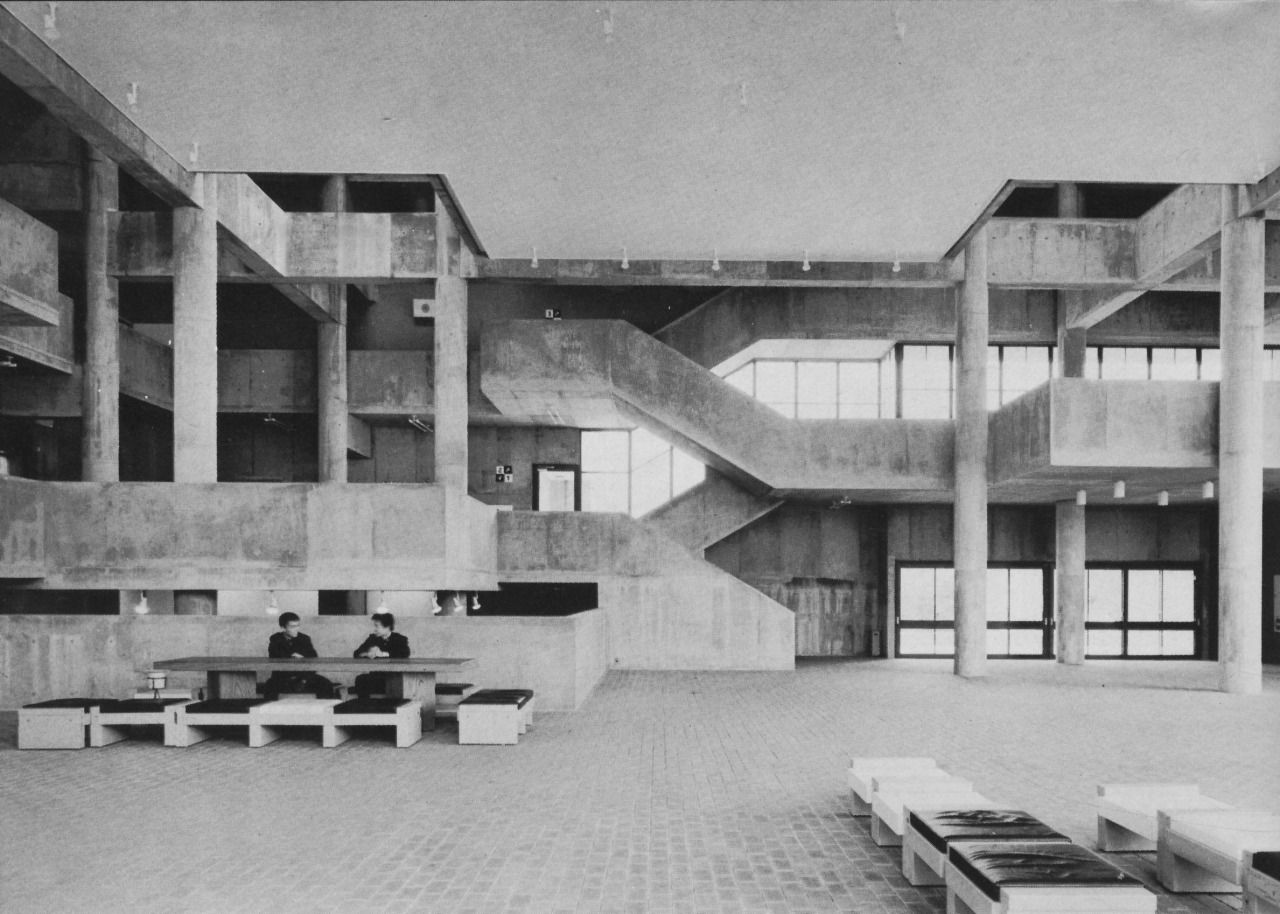

The comparisons between Archigram and the Metabolists are superficially easy, but whereas Archigram continued to publish increasingly preposterous and charming proposals throughout the 1960s, the Metabolists used their newly established reputations to snag large-scale commissions and quickly became distracted from generating additional futuristic sketches. Kikutake offered only one new scheme after the initial manifesto, whereas Maki and Otaka essentially refined their initial thesis without offering additional detail or production strategies. Only Kurokawa developed new proposals; his finest was the 1961 "Helix City." The international press tended to ignore the Metabolists' built work; in 1967, the journal Architectural Design titled an editorial essay "Whatever Happened to the Metabolists?" and concluded that the group was "static, if not extinct." At this point, the group's production included a number of buildings that clearly grappled with the movement's ideals, including Kikutake's Administrative building for Izumo Shrine (1963) and his odd, bellows-like Miyakonojo Civic Center (1966), Otaka's Hanaizumi Agricultural Cooperative Association Center (1965), Maki's Chiba University Auditorium (1963), and Rissho University (1967), and Kurokawa's Nitto Food Cannery (1964). Although the journal included thumbnail-sized photographs of a few built works, these were overwhelmed by the use of much larger illustrations dating from the original 1960 manifesto.

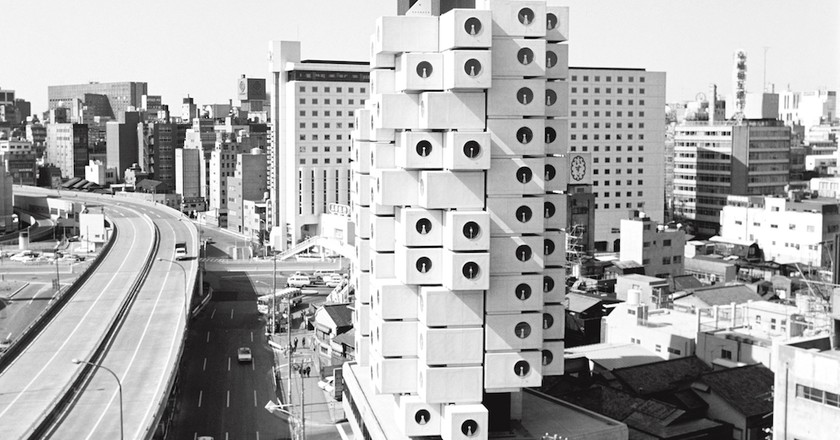

As the world withdrew its attention, the Metabolists were finding opportunities to build projects that most closely reflected their original intentions. Kurokawa produced the greatest range, from the Odakyu Drive-In Restaurant (1969) to the movement's most convincing commercial work, the Nakagin Capsule Building (1972), where shipping containers were modified for habitation and attached to core towers with only four bolts apiece. Several of Metabolism's key works from this period were for leisure facilities, a match that would seem on the surface appropriate; Kurokawa designed a lodge and a theme-based amusement complex, whereas Kikutake designed hotels for the domestic tourism industry. Although the leisure industry often most willingly embraces innovation, critics questioned the appropriateness of producing theoretic works for this market.

The 1970 Osaka Exposition appeared most in sync with a movement based on the idea of an architecture adaptable to change; many of the designers present in Metabolism's early days were involved, including Kikutake, Kurokawa, Tange, and Isozaki. Kikutake and Maki also had major commissions for the subsequent 1975 Okinawa Ocean Expo; Kikutake's Aquapolis, a remarkable pavilion floated just off shore, became a poignant symbol for the movement, unattainable and slowly rusting until it was scrapped at the end of the 20th century. However, The Osaka Exposition came a scant three years after the 1967 Montreal Expo and suffered by comparison. Category 1 expositions are usually spaced every six years, but an exception was made because of the Asian locale, a first. However, the resulting pavilions did not receive the same lavish support as at Montreal, and critics found most lacking verve. There were exceptions, especially Tange's extraordinary Festival Plaza, and the Toshiba IHP and Takara Pavilions by Kurokawa. Yet the subdued international response contributed to the Metabolist movement's collapse.

This is not to say, however, that Metabolism's adherents were persuaded that the movement's theories were irrelevant. Tange, Kikutake, and Kurokawa have each returned to their Metabolist beginnings in designs produced in the 1980s and 1990s. And many of the challenges that Metabolists took on—overcrowding, tremendous traffic congestion, and the immobility of Japanese society—remain today, yet to be adequately addressed by the professional community.

Dana BUNTROCK

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.2 (G-O). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

1959, Sky House, Tokyo, JAPAN, Kiyonori Kikutake |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1963, Administrative building for Izumo Shrine, Izumo, JAPAN, Kiyonori Kikutake |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1963, Chiba University Auditorium, Chiba, JAPAN, Fumihiko Maki |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1966, Miyakonojo Civic Center, Miyakonojo, JAPAN, Kiyonori Kikutake |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1967-1968, Rissho University, Kumagaya, JAPAN, Fumihiko Maki |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1972, the Nakagin Capsule Building, Tokyo, JAPAN, Kisho Kurokawa |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

KUROKAWA, KISHO

ISOZAKI, ARATA

MAKI, FUMIHIKO

TANGE, KENZO |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1959, Sky House, Tokyo, JAPAN, Kiyonori Kikutake

1963, Administrative building for Izumo Shrine, Izumo, JAPAN, Kiyonori Kikutake

1963, Chiba University Auditorium, Chiba, JAPAN, Fumihiko Maki

1966, Miyakonojo Civic Center, Miyakonojo, JAPAN, Kiyonori Kikutake

1967-1968, Rissho University, Kumagaya, JAPAN, Fumihiko Maki

1972, the Nakagin Capsule Building, Tokyo, JAPAN, Kisho Kurokawa |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

Ito, Toyo (Japan); Kurokawa, Kisho (Japan); Maki, Fumihiko (Japan); Tange, Kenzo (Japan)

FURTHER READING

Kawazoe, N., Kikutake, K., and Kurokawa, K., Metabolism 196o. Proposals for New Urbanism, Tokyo 1960; Kurokawa, K., The Concept of Metabolism, Tokyo 1972.

Banham, Reyner, Megastructure: Urban Futures of the Recent Past,

London: Thames and Hudson, and New York: Harper and Row,

1976

Boyd, Robin, New Directions in Japanese Architecture, New York:

Braziller, and London: Studio Vista, 1968

Jérome, Mike, “Whatever Happened to the Metabolists?”

Architectural Design 37, no. 5 (May 1967)

Kawazoe, Noboru, “From Metabolism to Metapolis—Proposal for a

City of the Future,” in Stadtstrukturen fiir Morgen, by Juscus

Dahinden, Stuttgart; Gerd Hatje, 1971; as Urban Structures for

the Future, wanslated by Gerald Onn, London: Pall Mall Press,

and New York: Praeger, 1972

Kurokawa, Kisho, Metabolism and Architecture, Boulder, Colorado:

‘Westview Press, 1977

Maki, Fumihiko and Masato Otaka, “Some Thoughts on Collective

Form” in Structure in Art and Science, edited by Gryorgy Kepes,

New York: Braziller, 1965

Metabolism: The Proposals for a New Urbanism, Tokyo: Bitjutu

Syuppan Sha, 1960

Bilingual manifesto released by the Metabolists. The volume is very

rare, but its illustrations and essays often served as the basis for

subsequent discussions of the movement

“Metabolist Kiyonori Kikutake,” Space Design, 10: 193 (October

1980)

Nitschke, Gunter, “The Metabolists of Japan,” Architectural Design

34, no. 10 (October 1964)

Nitschke, Ginter, “The Metabolists,” Architectural Design 37, no. 5

(May 1967)

Ross, Michael Franklin, Beyond Metabolism: The New Japanese

Architecture, New York: Architectural Records Books, 1978

Yatsuka, Hajime and Hideki Yoshimatsu, Metaborizumu:

SenKyuhyakurokujun Nendai, Nibon no Kenchiku Avan Gyarudo;

Metabolism: Japan's 1960 Architectural Avante-garde, Tokyo:

Inax Shuppan, 1997

Beyond Utopia: Japanese Metabolism Architecture and the Birth of Mythopia

Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-Garde |

| |

|

|