| ALL |

|

LIBRARY

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

The 20th century saw a remarkable transformation in library philosophy, away from the traditional understanding of the library as a treasure house that protected books from untrustworthy readers toward a new conception of the library as a building type that encouraged the encounter between readers and books. Pioneered in the United States, this new philosophy put particular emphasis on allowing readers free access to books stored on open shelves, providing children’s reading rooms, and establishing branch and traveling libraries. So radical was the idea of giving readers ready access to book collections that many public libraries did so only in conjunction with architectural mechanisms aimed at controlling readers. These included turnstiles (which forced readers to file one at a time past the charging desk) and the radial arrangement of bookshelves (which enhanced the ability of a single staff member to survey several aisles of bookshelves).

Because radial bookshelves were often housed in semi-circular rooms that were difficult to expand, their use was discontinued in the United States by about 1910. British librarians, however, continued to support the practice at least until 1920, when several versions of the arrangement were published in the third edition of James Duff Brown's Manual of Library Economy (1920). This new philosophy of service played a role in encouraging library philanthropy on an unprecedented scale, as industrialist Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919), newspaper editor John Passmore Edwards (1823-1911), and others financed public library buildings as a means of encouraging self-improvement among the working poor. Carnegie’s library building program was particularly noteworthy for the number of buildings Carnegie financed directly (1,469 in the United States alone, 2,507 worldwide), for its geographic extent (including England, Ireland, Scotland, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, Fiji, Mauritius, and elsewhere), for the innovations it introduced into the planning of small-town and branch libraries, and for the library building boom that it helped fuel even in communities that did not receive Carnegie funds.

The number of American public libraries more than quadrupled between 1896 and 1925, growing from 900 to 3,873. Formulated in consultation with progressive librarians, the Carnegie ideal was a one-story building without full-height interior partitions, an arrangement that enhanced administrative efficiency by giving the librarian seated at a centrally located charging desk an unencumbered view of the bookshelves lining the perimeter walls. Readers were allowed free access to the shelves, and half the space of the building was devoted to a children’s reading room. Although Carnegie recommended a simple exterior expression, many local decision makers adopted classicism in order to incorporate the library into the coordinated civic landscape advocated by the City Beautiful movement. The temple front and the triumphal arch were favorite compositional are often used with a dome whose lantern lighted the circulation area and transformed it into a locus of enlightenment, both literally and figuratively. Although many of these small public libraries received additions in the 1930s (with the help of W.P.A. funds) and during the post-war period, they continued to shape the public library experience for most Americans throughout the 20th century; according to American Libraries, at least 744 Carnegie-financed buildings in the United States were still used as libraries in 1990.

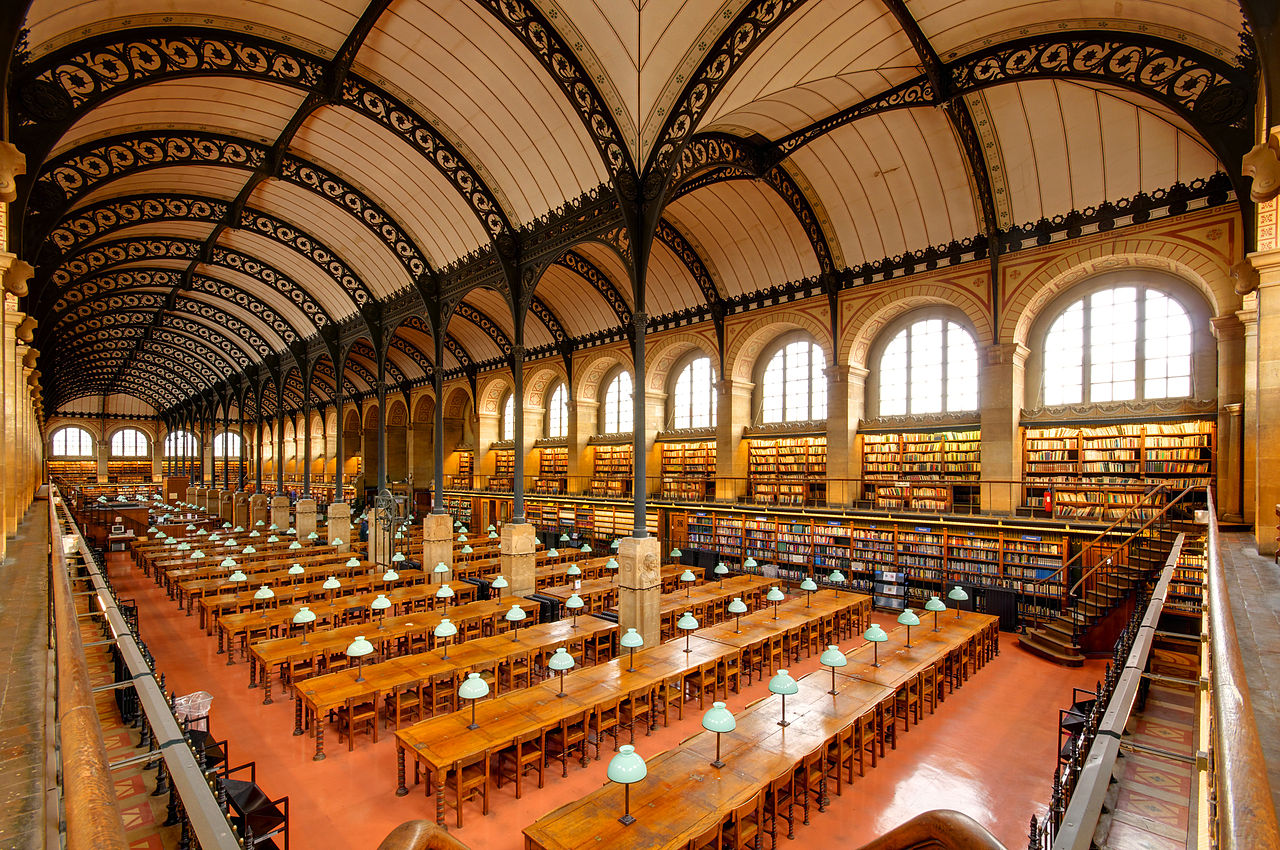

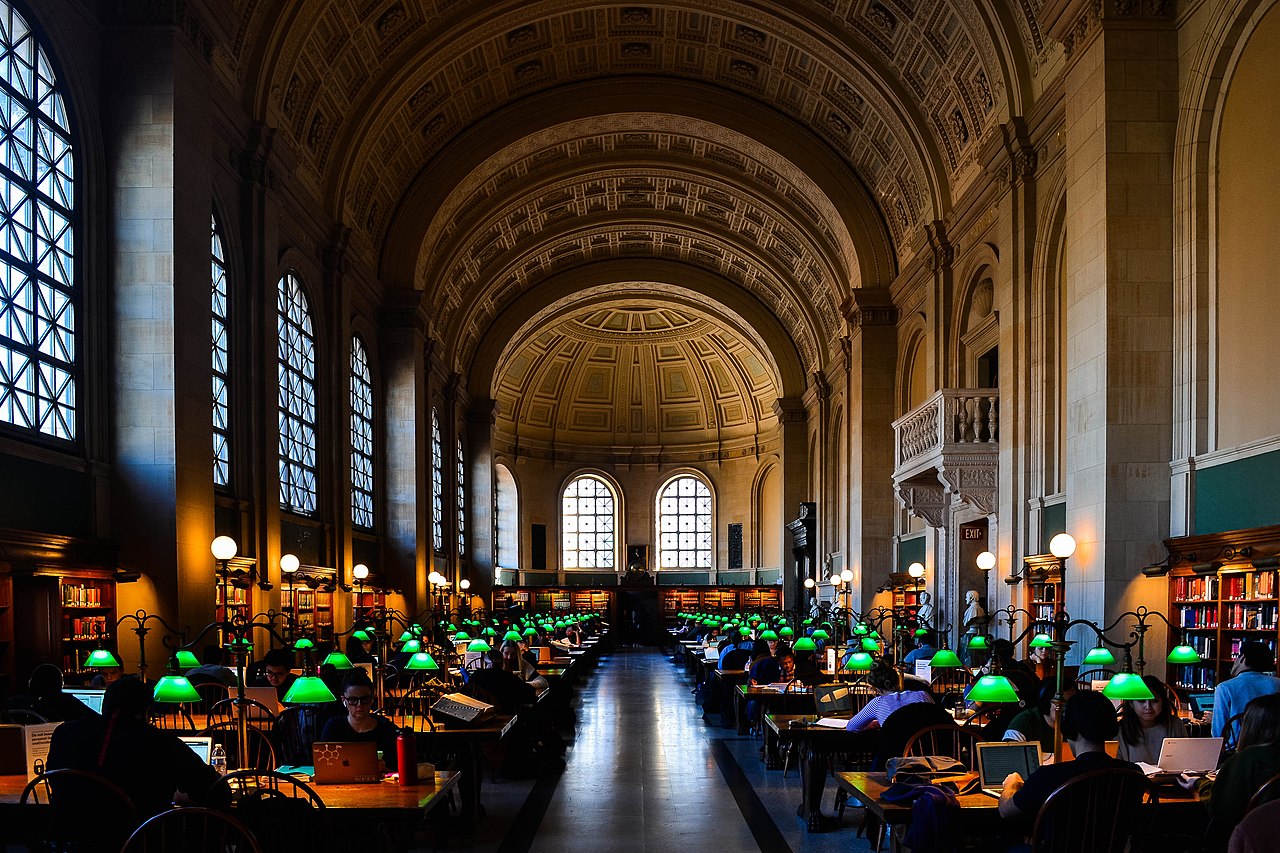

Standardized library equipment marketed nationally helped give early 20th-century library interiors their distinctive character. Established in 1888 by Melvil Dewey (1851-1931), a leading librarian and inventor of the Dewey decimal system, the Library Bureau offered a full range of library furniture and fittings that by the turn of the century tended toward golden oak Windsor chairs and cabinetry of a simplified classical form. Snead and Company specialized in the manufacture of self-supporting iron book stacks and by 1915 had completed more than 200 book-stack installations, including those at public libraries in Washington, D.C. (1901-03, Ackerman and Ross), Denver, Colorado (1904-10, Albert Randolph Ross), and Louisville, Kentucky (1904-08, Pilcher and Tachau), as well as at Harvard’s Widener Library (1912-15, Horace Trumbauer). The company also helped establish industry standards for shelf width (3 feet) and range spacing (4 feet, 6 inches on center). In contrast to the innovative forms of smaller libraries in this period, central libraries in larger cities (and several academic libraries) tended to follow patterns set by the great public libraries of the 19th century, particularly the Bibliothèque Ste-Geneviève (1844-50, Henri Labrouste) in Paris and the Boston Public Library (1888-95, McKim, Mead and White), each of which made reference to the Renaissance palazzo and featured closed book stacks and a monumental reading room on an upper floor. Twentieth-century examples include the public libraries in New York (1897-1911, Carrére and Hastings), St. Louis (1907-12, Cass Gilbert), Philadelphia (1912-27, Horace Trumbauer), Detroit (1913-21, Cass Gilbert), San Francisco (1914—17, George W. Kelham), and Indianapolis (1914-17, Paul P. Cret and Zantzinger, Borie and Medary), all of which located the book stacks at the back of the building, where long, narrow windows brought daylight into the aisles.

In the interwar years, monumental classical exteriors were still the norm for central libraries in larger American cities, but these now often cloaked internal arrangements aimed at bringing readers and books closer together. One approach was to locate the book stack in the center of the building, surrounding it with reading rooms. Another was to disperse the collection, placing books in closer proximity to reading rooms, as was done in Los Angeles (1922-26, Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue). A third approach was to put the brunt of the book collection on a lower level. This approach is associated particularly with New York architect Edward L. Tilton (1861-1933), who first introduced it at the Springfield (Massachusetts) Public Library (1907-12) and later used it to provide an open plan for the main floor of large urban libraries; the Somerville (Massachusetts) Public Library (opened 1913) and the Enoch Pratt Free Library (1928-33, Tilton and Githens, consulting architects) in Baltimore, Maryland, are noteworthy examples. The Enoch Pratt building was built during the tenure of librarian Joseph L. Wheeler (1884-1970), who embraced an aggressive approach to attracting readers to the library and encouraged Tilton to emulate some of the characteristics of the department store in his library design: a facade set directly on the lot line, a sidewalk-level entrance, and large display windows. By mid-century, Wheeler was a prominent library building consultant and co-author of The American Public Library Building (1941) with Tilton’s former partner, architect Alfred Morton Githens. In other contexts, architects took advantage of basement-level book storage to develop varied and dramatic building sections, as Alvar Aalto did at the Viipuri City Library (1927-35) in Finland. There, adult readers entered the building

one level above the book storage area and climbed up another level to the main lending room, which in turn acted as a gallery that allowed the librarian’s desk to overlook the main reading room and a smaller reading mezzanine; skylights brought daylighting into all these reading areas.

During the 1930s, self-supporting multi-tiered book stacks were reaching their greatest heights; Yale’s Sterling Library (designed by James Gamble Rogers) rose to 16 tiers when it opened in 1931. At the same time, however, academic librarians began to question whether such stacks were the best mode of book storage. Prompted by pedagogical innovations, such as the seminar system that involved students in intensive library use, academic librarians were unhappy with the inflexible character of the book stacks, whose standard tier height (established by Snead and Company at seven feet, six inches) and dim lighting made them unpalatable places for reading. Angus Snead Macdonald (1883-1961), president of Snead and Company, formulated a more flexible system of library planning that employed a nine-by-nine-foot planning module (which allowed librarians to locate standardized book shelving anywhere in the library) and an eight-foot ceiling height (which offered a compromise between shelving efficiency and reader comfort). Although the particular dimensions of the module continued to evolve (by 1955, Macdonald advocated modules as large as 27 by 27 feet), the modular library became the norm for public and academic libraries in the decades after World War II, including among the first the Firestone Memorial Library at Princeton University (1944-48, R.B. O'Connor and Walter H. Kilham Jr). As reading space and book storage space became integrated on each floor, the rectangular footprint of these buildings tended to grow, as did the library’s dependence on air conditioning, fluorescent lighting, and flat ceilings. Although the doctrine of flexible planning offered exciting possibilities in library service, the architectural spaces that it created often were monotonous.

Particularly important to these developments was the Cooperative Committee on Library Building Plans, a loosely defined group of architects, academic librarians, and university administrators who met between 1944 and 1952 to discuss library design. In addition to Macdonald, the group included Keyes D. Metcalf (1889-1983) of Harvard University, who became an important library consultant in the 1950s and 1960s and who wrote the bible of modular library planning, Planning Academic and Research Library Buildings (1965). Discussions of modular library planning also took place at Library Building Institutes, sponsored by the American Library Association, from the mid-1940s until 1967. In the face of predictions that the computer would make the library obsolete, the last 20 years of the 20th century saw a renewed interest in library architecture, with a particular emphasis on large central public libraries that can serve a sizable audience by reaching further afield for library users while aiding in the economic redevelopment of urban centers. Several of these libraries have been the subject of national or international design competitions, including the Joensuu Library (1982-83, Heikkinen and Siitonen Architects) in Finland, The Hague City Library (1986-95, Richard Meier and Partners), the Harold Washington Library Center (1988-91, Hammond Beeby and Babka) in Chicago, and the Vancouver Central Public Library (1992-95, Moshe Safdie and Associates with Downs Archambault and Partners). In Denver, Colorado, Michael Graves transformed and expanded the existing 1956 Central Library (Fisher and Fisher/ Burnham Hoy) with his 1995 structure located adjacent to the historic Civic Center Park.

In the last decades of the 20th century, there was also a concerted effort to make libraries delightful places to read. Architects became concerned with the provision of natural light and with the manipulation of the ceiling plane to create reading spaces that were either monumental, as at the fifth-floor reading room of the Phoenix Central Library (1989-95, bruderDWL Architects), or intimate, as in the galleries of the Vancouver Central Public Library or in the reading alcoves of the Humboldt Library (1984-88, Moore Ruble Yudell) in Berlin. Typically, these spaces are the product of junctional zoning within the building, a version of the fixed-function planning that characterized pre-war library design. Sometimes this zoning has been accomplished within a modular grid and square footprint, as at the Tonsberg (Norway) Public Library (1988-92, Lunde and Lovseth). More often, however, libraries of the late 20th century used irregular plans to give the various functions their own spatial articulation; notable examples of this approach include the Minster City Library (1987-93, Architekturbiiro Bolles-Wilson and Partner) and the Almelo Public Library (1991-94, Mecanoo) in the Netherlands.

Equally important, there has also been a renewed appreciation for older library buildings. Late 19th-century buildings in the grand manner have been lovingly restored; readers are once again welcomed through the main doors of the Boston Public Library on Copley Square and encouraged to experience the original entry sequence: up the main stairs, past newly cleaned mural paintings, to the main reading room. More modest libraries from the early 20th century are also enjoying a renaissance, as cities such as Seattle work to revitalize the historic character of their numerous Carnegie-financed branches. At the dawn of the 21st century, library architecture is again as vital and exciting as it was at the beginning of the 20th.

Abigail A. VAN SLYCK

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.2 (G-O). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1850, Sainte-Geneviève Library, Paris, FRANCE, Henri Labrouste |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1895, Boston Public Library, McKim Building, Boston, USA, McKim, Mead and White |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1907-1912, the Springfield Public Library, Springfield, USA, Edward L. Tilton |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1924-1928, the Stockholm Public Library, Stockholm, SWEDEN, ERIK GUNNAR ASPLUND |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927-1935, the Viipuri City Library, Vyborg, RUSSIA, Alvar Aalto |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

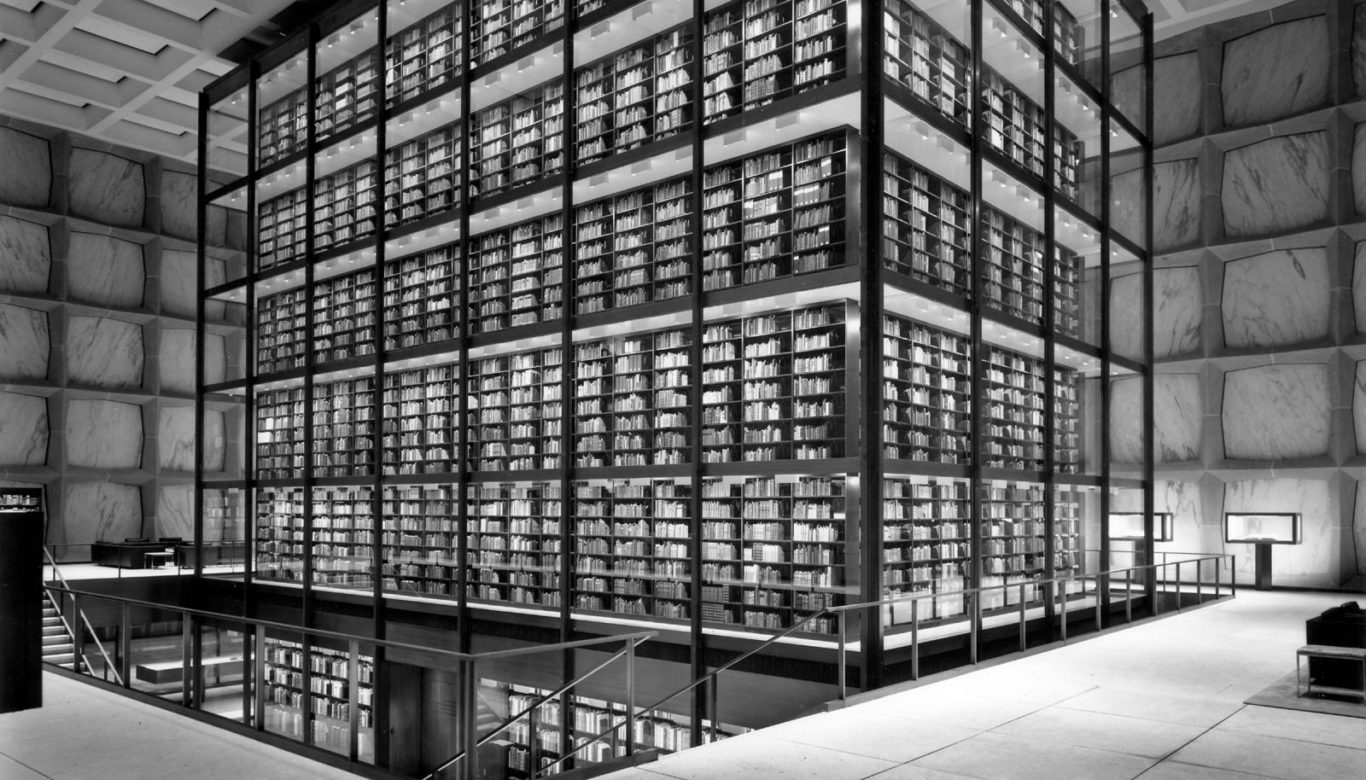

1963, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, New Haven, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

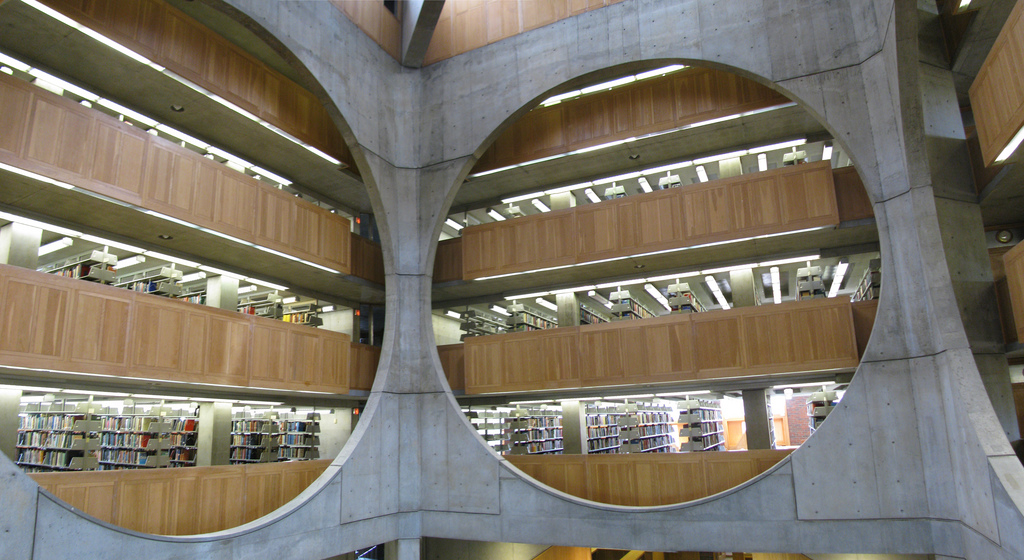

1965-1971, Library and Dining Hall, Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1972, Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, Washington, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1976-1979, Library at the Capuchins convent, Lugano, Switzerland, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1979, John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1981, Keio University Library, Mita Campus, Tokyo, JAPAN, FUMIHIKO MAKI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1984-1988, Library, Villeurbanne, France, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1984-1988, the Humboldt Library, Berlin, GERMANY, Moore Ruble Yudell |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1987-1993, Minster City Library, Münster, GERMANY, Architekturbiiro Bolles-Wilson and Partner |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1988-1992, the Tonsberg Public Library, Tonsberg, NORWAY, Lunde and Lovseth |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1989-1995, the Phoenix Central Library, Phoenix, USA, bruderDWL Architects |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1992, Cranfield University Library, Cranfield, UK, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

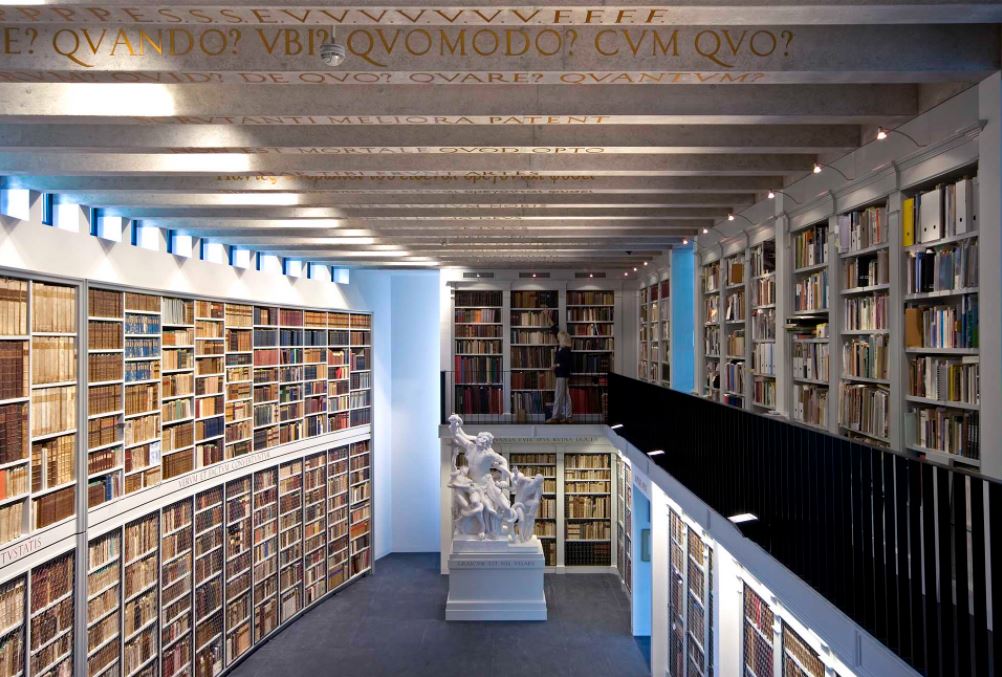

1992-2004, Werner Oechslin Libary, Einsiedeln , SWITZERLAND, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1993, Carré d'Art, Nîmes, France, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1995-1999, Municipal library, Dortmund, Germany, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1995-2004, Library “Tiraboschi”, Bergamo, Italy, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1999-2004, Seattle Central Library, Seattle, USA, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2000-2006, RENOVATION AND EXPANSION OF THE MORGAN LIBRARY, NEW YORK, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

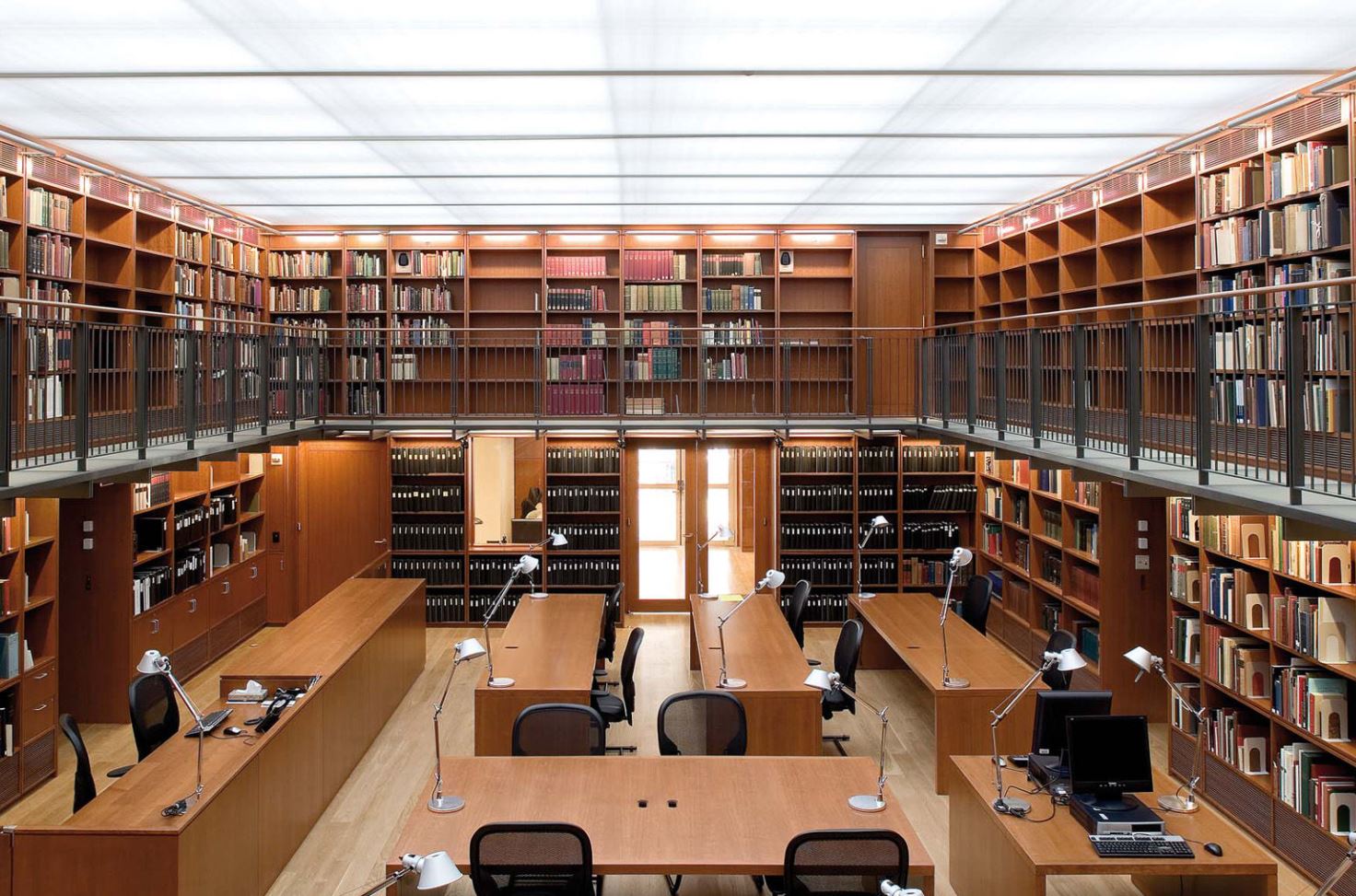

2002-2016, BIBLIOTECA UNIVERSITARIA DI TRENTO, TRENTO, ITALY, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2003, Salt Lake City Public Library, Salt Lake City, USA, MOSHE SAFDIE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2003, Library for the Indian Parliament, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

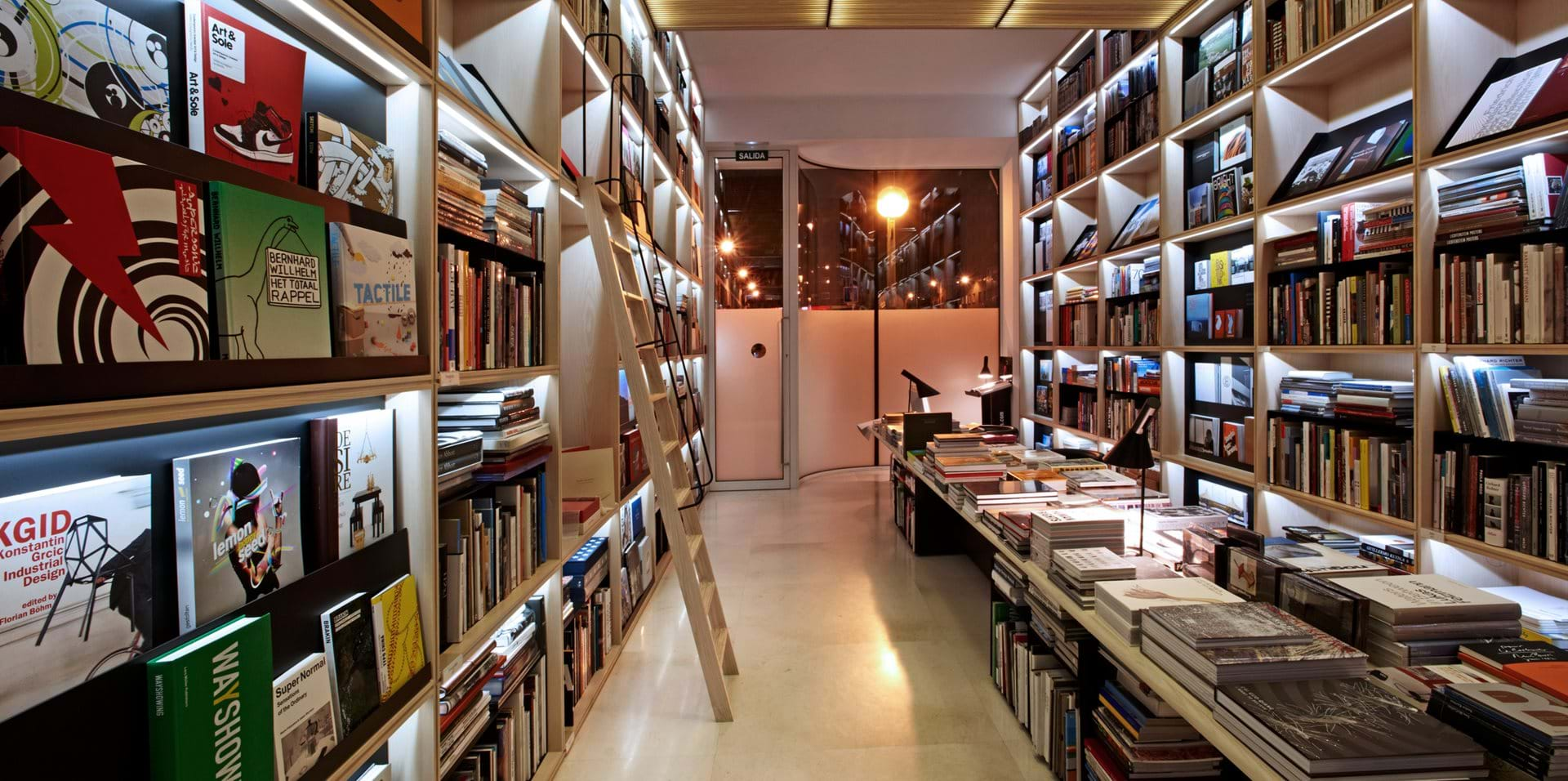

2008, Ivorypress, Madrid, Spain, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2008-2011, Humanities and Social Sciences Library of the Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2017, Qatar National Library , Doha, QATAR, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

AALTO, ALVAR

BOTTA, MARIO

FOSTER, NORMAN

KOOLHAAS, REM

MAKI, FUMIHIKO

PIANO, RENZO

TANGE, KENZO |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1850, Sainte-Geneviève Library, Paris, FRANCE, Henri Labrouste |

| |

|

| |

1895, Boston Public Library, McKim Building, Boston, USA, McKim, Mead and White |

| |

|

| |

1907-1912, the Springfield Public Library, Springfield, USA, Edward L. Tilton |

| |

|

| |

1924-1928, the Stockholm Public Library, Stockholm, SWEDEN, ERIK GUNNAR ASPLUND |

| |

|

| |

1927-1935, the Viipuri City Library, Vyborg, Russia, Alvar Aalto |

| |

|

| |

1931, Yale’s Sterling Library, Yale, USA, James Gamble Rogers |

| |

|

| |

1953, Hiroshima Children’s Library, Hiroshima, JAPAN, KENZO TANGE |

| |

|

| |

1965-1971, Library and Dining Hall, Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

1963, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library,

New Haven, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

1972, Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library, Washington, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

1976-1979, Library at the Capuchins convent, Lugano, Switzerland, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1979, John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library,

Boston, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

1981, Keio University Library, Mita Campus, Tokyo, JAPAN, FUMIHIKO MAKI |

| |

|

| |

1984-1988, Library, Villeurbanne, France, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1992, Cranfield University Library, Cranfield, UK, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

1992-2004, Werner Oechslin Libary, Einsiedeln , SWITZERLAND, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1993, Carré d'Art, Nîmes, France, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

1995-1999, Municipal library, Dortmund, Germany, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1995-2004, Library “Tiraboschi”, Bergamo, Italy, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1999-2004, Seattle Central Library, Seattle, USA, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

2000-2006, RENOVATION AND EXPANSION OF THE MORGAN LIBRARY, NEW YORK, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2001, LSE Library, London, UK, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

2002-2016, BIBLIOTECA UNIVERSITARIA DI TRENTO, TRENTO, ITALY, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2003, Fukui Prefectural Library and Archives, Fukui, JAPAN, FUMIHIKO MAKI |

| |

|

| |

2003, Salt Lake City Public Library,

Salt Lake City, USA, MOSHE SAFDIE |

| |

|

| |

2003, Library for the Indian Parliament, New Delhi, India, RAJ REWAL |

| |

|

| |

2008, Ivorypress, Madrid, Spain, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

2008-2011, Humanities and Social Sciences Library of the Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

2013, "L'Ourse" Public Library, Dinard, France, RICARDO BOFILL |

| |

|

| |

2017, Qatar National Library , Doha, QATAR, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

FURTHER READING

In addition to the specific sources listed below, Library Journal has since 1945 devoted one of its December issues to articles on library architecture.

Baumann, Charles H., The Influence of Angus Snead Macdonald and

the Snead Bookstack on Library Architecture, Metuchen, New

Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1972

Bobinski, George S., Carnegie Libraries; Their History and Impact on

American Public Library Development, Chicago: American Library

Association, 1969

Brawne, Michael, Library Builders, London and Lanham, Maryland:

Academy Editions, 1997

Brown, James Duff, Manual of Library Economy, London: Scott

Greenwood, 1903; 7th edition, rewritten by R. Northwood Lock,

London: Grafton, 1961

“Inviting Places,” American Libraries, 21/4 (April 1990)

Kaser, David, The Evolution of the American Academic Library

Building, Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 1997

Metcalf, Keyes DeWitt, Planning Academic and Research Library

Buildings, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965; 2nd edition, by Philip

D, Leighton and David C. Weber, Chicago: American Library

Association, 1986

Oehlerts, Donald E., Books and Blueprints: Building America’s Public

Libraries, New York: Greenwood Press, 1991

Spens, Michael, Viipuri Library, 1927-1935, Alvar Aalto, London

and New York: Academy Editions, 1994

Thompson, Anthony, Library Buildings of Britain and Europe: An

International Study, with Examples Mainly from Britain and Some

from Europe and Overseas, London: Butterworths, 1963

Van Slyck, Abigail A., Free to All: Carnegie Libraries and American

Culsure, 1890-1920, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995

Wheeler, Joseph Lewis, and Alfred Morton Githens, The American

Public Library Building, New York: Scribner, and Chicago:

American Library Association, 1941

Libraries and Librarianship: Sixty Years of Challenge and Change, 1945-2005

|

| |

|

|