| ALL |

|

CONSTRUCTIVISM

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

For the 15 or so years of its existence, from the first years of Soviet power to the early 1930s, Constructivism endeavored to alter conceptions of architectural space, to create an environment that would inculcate new social values, and at the same time to use advanced structural and technological principles. Paradoxically, the poverty and social chaos of the early revolutionary years propelled architects toward radical ideas of design, many of which were related to an already thriving modernist movement in the visual arts. For example, El Lissitzky’s concepts of space and form, along with those of Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935) and Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953), played a major part in the development of an architecture expressed in “stereometric forms,” purified of the decorative elements of the eclectic past.

The experiments of Lissitzky, Vasily Kandinsky, and Malevich in painting and of Tatlin and Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956) in sculpture had created the possibility of a new architectural movement, defined by Lissitzky as a synthesis with painting and sculpture.

In its initial phase, Constructivism was closely associated with radical design studios. The preeminent institution was named VKhUTEMAS (the Russian acronym for “Higher Artistic and Technical Workshops”), following a reorganization of the Free Workshops in 1920. In 1925 it was reorganized yet again, subse quently to be called the Higher Artistic and Technical Institute (VKhUTEIN). VKhUTEMAS-VKhUTEIN was by no means the only Moscow institution concerned with the teaching and practice of architecture in the 1920s, but it was unique in the scope of its concerns (which included the visual and the applied arts) as well as in the variety of programs and viewpoints that existed there before its closing in 1930.

Theoretical direction for VKhUTEMAS was provided by the Institute of Artistic Culture (INKhUK, also founded in 1920), which attempted to establish a science “examining analytically and synthetically the basic elements both for the separate arts and for art as a whole.” Its first program curriculum, developed by Kandinsky, was found too abstract by many at INKhUK, and Kandinsky soon left for Germany and the Bauhaus.

However, the concern with abstract, theoretical principles did not abate with Kandinsky’s departure. Indeed, the issue of theory versus construction became a major source of factional dispute in Russian modernism. The crux of the debate between the rationalists, or formalists, and the Constructivists lay in the relative importance assigned to aesthetic theory as opposed to a functionalism derived from technology and materials.

Constructivist ideologues maintained that the work of the architect must not be separated from the utilitarian demands of technology. The Constructivist theoretician Moisei Ginzburg (1892–1946) accused the rationalists of ignoring this principle. ASNOVA, the main rationalist group that included Nikolai Ladovsky (1881–1941), Vladimir Krinsky (1890–1971), Nikolai Dokuchaev (1899–1941), and for a time Lissitzky, countered by accusing the Constructivists of “technological fetishism.”

Yet both groups shared a concern for the relation between architecture and social planning, and both insisted on a clearly defined structural mass based on uncluttered geometric forms and drew inspiration from modernism in painting and sculpture.

The principles of Constructivism is demonstrated in the work of Alexander Rodchenko, who in 1921 defined construction as the contemporary demand for organization and the utilitarian application of materials. Equally influential was the work of Lissitzky and Malevich, whose abstract architectonic models (Lissitzky’s “Prouns,” and Malevich’s planity or arkhitektony) represented the ultimate refinement in “pure” spatial forms. For Malevich, architectonic forms were a logical extension of his “Suprematism.”

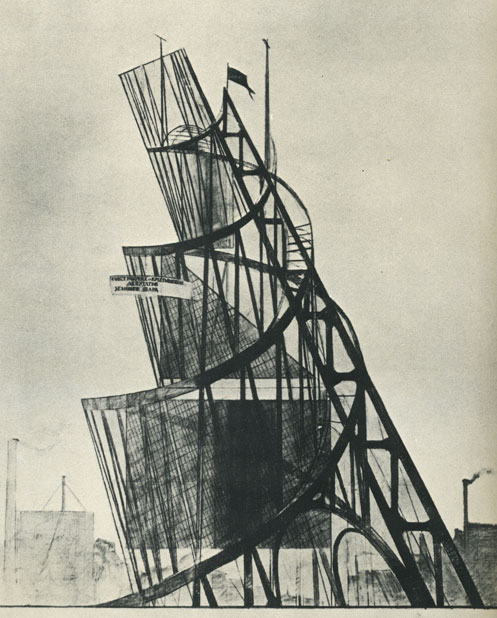

Even as art (and sculpture) continued to exert a profound influence on the development of modern architectural design, so architecture came to be seen as the dominant, unifying element in a synthesis of art forms. The most dramatic expression of artistic form as a function of material revealed in space was Tatlin’s Utopian project for a monument to the Third International (1919–20), intended to be 400 meters in height, with a spiral steel frame containing a rotating series of geometric forms. The monument was dismissed as technologically infeasible when the large model constructed by Tatlin was brought to Moscow for exhibition and discussion. Yet the designs of Tatlin, Lissitzky, and other architects and students at the VKhUTEIN workshops gave notice of a new movement that glorified the rigorous logic of undecorated form as an extension of material and that intended to participate fully in the shaping of Soviet society.

In the early 1920s, the evolution of Constructivist ideas at INKhUK passed through a number of polemical phases (the term konstruktivizm was still broadly interpreted and had not yet acquired the “functionalist” architectural emphasis of the mid-1920s). The pure-art faction, influenced by Kandinsky, was opposed by the “productionists” (associated with the Left Front of the Arts), who anticipated an age of engineers supervising the mass production of useful, nonartistic objects. A reaction to both sides, particularly the former, led in 1921 to the formation of a group of artists-constructivists: Alexander Vesnin, architect; Aleksei Gan, art critic and propagandist; Rodchenko, sculptor and photographer; Vladimir and Georgii Sternberg, poster designers; and Varvara Stepanova (1894–1958), artist and set designer.

Until 1925 the Constructivists had little more to show in actual construction than their more theoretically minded colleagues, the rationalists. The exigencies of social and economic reconstruction drastically limited the resources available, particularly for structures requiring a relatively intensive use of modern technology. In fact, the most advanced of Constructivist works in the early 1920s were wooden set designs by Alexander Vesnin, Varvara Stepanova, and Liubov Popova. By 1924 Constructivist architects, whatever their tangible achievements, had acquired vigorous leadership in the persons of Alexander Vesnin and Moisei Ginzburg.

In 1924 Ginzburg’s book Style and Epoch appeared in print and established the theoretical and historical base for a new architecture in a new age, devoid above all of the eclecticism and aestheticism of capitalist architecture at the turn of the century. The following year the Constructivists founded the Union of Contemporary Architects (OSA), and in 1926 the Union began publishing the journal Contemporary Architecture, edited by Ginzburg and Vesnin.

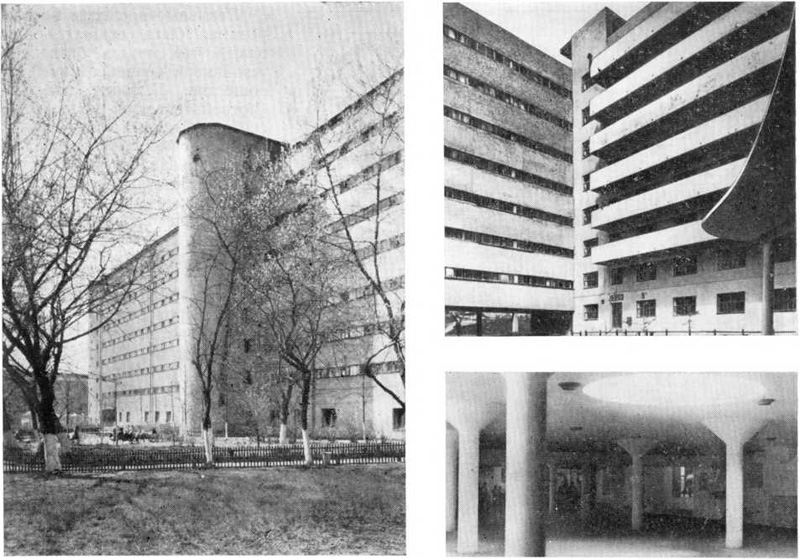

Perhaps the most accomplished example of the functional aesthetic is Ginzburg’s own creation, the apartment house for the People’s Commissariat of Finance (1928–30) at Narkomfin, designed in collaboration with Ivan Milinis. The smaller scale of the Narkomfin building (intended for 200 residents) contributed only marginally to a solution for resolving the urban housing crisis, but it illustrates Ginzburg’s statements on the necessary interdependence of aesthetics and functional design, from the interior to the exterior.

Built to contain apartments, as well as dormitory rooms arranged in a communal living system, the interior was meticulously designed, like that of many Constructivist buildings. The main structure, adjoined at one end by a large block for communal services, rested on pilotis (now enclosed), and the structure culminated in an open-frame solarium. The front, or east, facade of the building is defined by the sweeping horizontal lines of window strips and, on the lower floors, of connecting balconies.

Ginzburg’s concept of functionalism for the Narkomfin project shows similarities to the work of Gropius and De Stijl. The closest affinity, however, is with Le Corbusier’s notion of the Unite d’Habitation. (Le Corbusier and Ginzburg were personally acquainted, and in 1927 the French architect was included on the board of Contemp orary Architecture.) Larger communal apartment buildings of the period were necessarily less refined in detail, yet a few examples, such as Ivan Nikolaev’s massive eight-story dormitory (1000 rooms, each six square meters, for 2000 students) built in 1929–30 on Donskoi Lane in south Moscow, were strikingly futuristic in the streamlined contours of their machine-age design. Other notable examples of Constructivist architecture in Moscow include the Izvestiia Building (1927) by Grigory Barkhin (1880–1969), the Zuev Workers’ Club (1927–29) by Ilya Golosov (1883–1945), the State Trade Agency (1925–27) in Gostorg by Boris Velikovsky (1878–1937), and the Commissariat of Agriculture (1929–33) by Aleksei Shchusev (1873–1949).

The most productive proponents of Constructivism were the Vesnin brothers: Leonid, Viktor, and Alexander. Among their most significant works are the Mostorg Department Store (1927–29), the club for the Society of Tsarist Political Prisoners (1931–34), and a large complex of three buildings (1932–37) to serve as a workers’ club and House of Culture for the Proletarian District, a factory and district in southeast Moscow.

Constructivism was by no means confined to Moscow. Many other Soviet cities, such as Leningrad, Nizhnii Novgorod (or Gorky), Sverdlovsk, Novosibirsk, Kazan, and Kharkov, saw the implementation of major projects that illustrated the extent to which ideas developed by the Constructivists had been assimilated into architectural practice. In Kharkov a massive complex of several buildings known as the State Industry Building (Gosprom, 1926–28) was designed by an architectural team headed by Sergei Serafimov (1878–39). In Sverdlovsk, whose entire city center was redesigned with the participation of architects such as Moisei Ginzburg, a large housing and office development known as Chekists’ Village (1929–38) was designed by I.Antonov, V.Sokolov, and A.Tumbasov. In Leningrad, which under the direction of Sergei Kirov had begun to recover from its precipitous economic and political decline following the revolution.

Constructivist architecture was particularly noticeable in the design of administrative and cultural centers for the city’s largest outer districts, where workers’ housing was under construction. (The historic central districts of the city remained largely intact by virtue of a comprehensive preservation policy and the limited resources of an abandoned capital.)

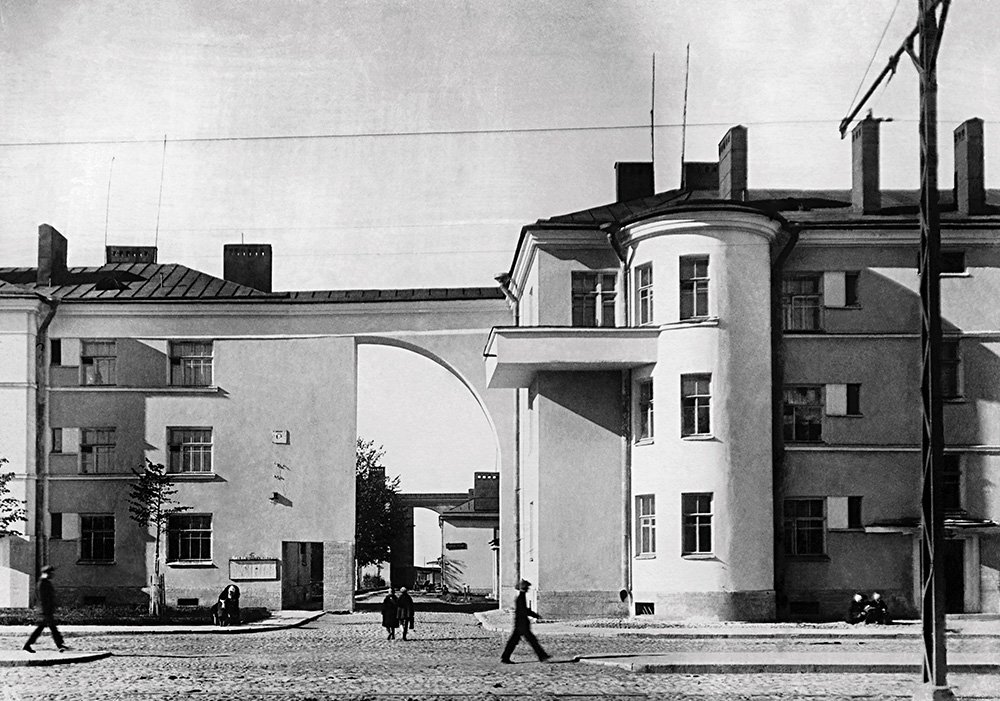

One of the earliest examples of Constructivism in Leningrad was the Moscow-Narva District House of Culture (1925–27; later renamed the Gorky Palace of Culture) by Alexander Gegello (1891–1965) and David Krichevsky. Essentially a symmetrical structure designed around a wedge-shaped amphitheater of 1900 seats, the compact building demonstrated the beginnings of a functional monumentality dictated by actual circumstances—ignored in the earlier Workers’ Palace and Palace of Labor competitions.

The construction of a number of model projects occurred in the same district, including workers’ housing (1925–27) by Gegello and others on Tractor Street, and a department store and “factory-kitchen” (1920–30; to eliminate the need for cooking at home) in a streamlined early Bauhaus style by Armen Barutchev (1904–76) and others, and the Tenth Anniversary of October School (1925–27) designed by Alexander Nikolsky on Strike Prospekt. The centerpiece of the district (subsequently renamed Kirov) was the House of Soviets (1930–34) designed by Noi Trotsky (1895–1940). Its long, four-story office block, defined by horizontal window strips, ends on one side in a perpendicular wing with a rounded facade and on the other in a severely angular ten-story tower with corner balconies.

A similarly austere, unadorned style emphasizing the basic geometry of forms was adopted by Igor Ivanovich Fomin (1903–) and A.Daugul (1900–41) for the Moscow District House of Soviets (1931–35) on Moscow Prospekt. Yet the facade, composed of segmented windows of identical size, signifies the repetition of an incipient bureaucratic style rather than the streamlined dynamic of earlier Constructivist work.

Despite the appearance of late examples of Constructivist architecture, such as the Pravda Building (1931–35) by Panteleimon Golosov (1882–1945), Soviet architectural design during the 1930s increasingly adopted historicist approaches to the articulation of structure, whether derived from variants of neoclassicism or skyscraper Gothic. Only in the 1960s did critical interest in Constructivist concepts and innovations begin to revive.

Although the Constructivist legacy was long ignored in the Soviet Union, it must be emphasized that Constructivism and the related art of the avant-garde experienced considerable success in Europe. Lissitzky, who spent 1922–25 in Germany, served admirably as a propagandist for the movement, and ties between INKhUK and the Bauhaus were close. During the 1920s many Russian artists active at VKhUTEMAS and INKhUK visited the West (Kandinsky, Malevich, Gabo, and Pevsner), while Western architects visited, and in many cases worked in, the Soviet Union (Bruno Taut, Ernst May, Erich Mendelsohn, and Le Corbusier). Exhibitions of modernist Soviet art were held in various European cities as well as in New York, and Western journals, such as L’Esprit Nouveau and De Stijl, wrote of Constructivism and of the latest developments in Russian architecture. Western interest in the legacy of Constructivism continues to this day in the form of numerous publications and major museum exhibitions devoted to the work of the Constructivists.

WILLIAM C.BRUMFIELD

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2004. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

1919-1920, a monument to the Third International, Vladimir Tatlin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Rodchenko's Advertising poster, Alexander Rodchenko

|

| |

|

| |

, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS.jpeg) |

| |

1923, Palace of Labor (Third prize, competition), Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS.jpeg) |

| |

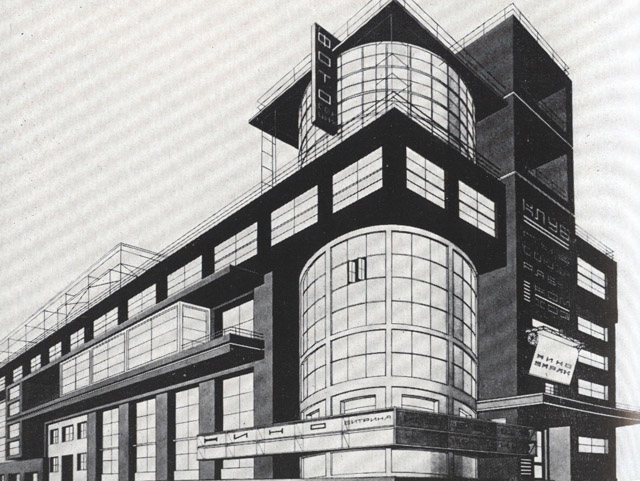

1924, Pravda Newspaper Building (unbuilt), Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

, Leningrad, USSR, Alexander Gegello and David Krichevsky.jpeg) |

| |

1925-1927, House of Culture (later renamed the Gorky Palace of Culture), Leningrad, USSR, Alexander Gegello and David Krichevsky |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925-1927, the Tenth Anniversary of October School, Leningrad, USSR, Alexander Nikolsky |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1926-1928, the State Industry Building, Gosprom, MOSCOW, USSR, Sergei Serafimov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927, The workers’ housing on Tractor Street, Leningrad, USSR, Alexander Gegello |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927, Izvestiia Building, MOSCOW, USSR, Grigory Barkhin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927-1929, the Zuev Workers’ Club, MOSCOW, USSR, Ilya Golosov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928, Food Factory #1, MOSCOW, USSR, Alexey Meshkov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928-1930, the apartment house for the People’s Commissariat of Finance, MOSCOW, USSR, Moisei Ginzburg |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1929, Mostorg Department Store, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1929-1930, Dormitory, MOSCOW, USSR, Ivan Nikolaev |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1929-1933, the Commissariat of Agriculture, MOSCOW, USSR, Aleksei Shchusev |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

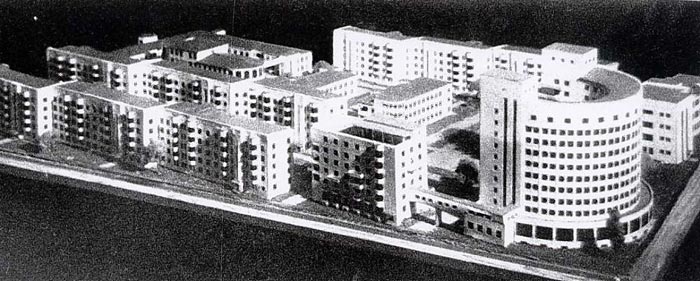

1929-1938, Chekists’ Village, Sverdlovsk, USSR, I.Antonov, V.Sokolov, and A.Tumbasov. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1930, Student housing of Communist University of the National Minorities of the West, Moscow, USSR, G. Dankman |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1930-1935, the Moscow District House of Soviets , Moscow, USSR, Igor Fomin and A.Daugul |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1931-1935, the Pravda Building, Moscow, USSR, Panteleimon Golosov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1934, Society of Tsarist Political Prisoners Club, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1937, Proletarian Region Club,

Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

LE CORBUSIER

GINZBURG, MOISEI

GOLOSOV, ILYA

LEONIDOV, IVAN ILICH

VESNIN, ALEXANDER, LEONID VESNIN, AND VIKTOR VESNIN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1919-1920, a monument to the Third International, Vladimir Tatlin

1920-1930, a department store and “factory-kitchen”, Leningrad, USSR, Armen Barutchev

1923, Palace of Labor (Third prize, competition), Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS

1924, Pravda Newspaper Building (unbuilt), Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS

1925-1927, the State Trade Agency in Gostorg, MOSCOW, USSR, Boris Velikovsky

1925-1927, House of Culture (later renamed the Gorky Palace of Culture), Leningrad, USSR, Alexander Gegello and David Krichevsky

1925-1927, the Tenth Anniversary of October School, Leningrad, USSR, Alexander Nikolsky

1926-1928, the State Industry Building, Gosprom, MOSCOW, USSR, Sergei Serafimov

1927, The workers’ housing on Tractor Street, Leningrad, USSR, Alexander Gegello

1927, Izvestiia Building, MOSCOW, USSR, Grigory Barkhin

1927-1929, the Zuev Workers’ Club, MOSCOW, USSR, Ilya Golosov

1928-1930, the apartment house for the People’s Commissariat of Finance, MOSCOW, USSR, Moisei Ginzburg

1929, Mostorg Department Store, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS

1929-1930, Dormitory, MOSCOW, USSR, Ivan Nikolaev

1929-1933, the Commissariat of Agriculture, MOSCOW, USSR, Aleksei Shchusev

1929-1938, Chekists’ Village, Sverdlovsk, USSR, I.Antonov, V.Sokolov, and A.Tumbasov.

1930-1934, the House of Soviets, Leningrad, USSR, Noi Trotsky

1930-1935, the Moscow District House of Soviets , Moscow, USSR, Igor Fomin and A.Daugul

1931-1935, the Pravda Building, Moscow, USSR, Panteleimon Golosov

1934, Society of Tsarist Political Prisoners Club, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS

1937, Proletarian Region Club,

Moscow, RUSSIA, Vesnin brothers |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

MOSCOW; RUSSIA and USSR; SOVIET ARCHITECTURE; ST. PETERSBURG

FURTHER READING

Constructivism is likely the most extensively studied topic within Russian architectural history. Western scholars, as well as Russian specialists such as Khan-Magomedov, have written prolifically on the movement as a whole and on specific architects and artists associated with it.

Barkhin, M.G., et al. (editors), Mastera sovetskoi arkhitektury ob arkhitekture (Masters of Soviet Architecture on Architecture), 2 vols., Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1975

Bliznakov, Milka, “The Realization of Utopia: Western Technology and Soviet AvantGarde Architecture,” in Reshaping Russian Architecture, edited by William Brumfield, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991

Borisova, Elena A., and Tatiana P.Kazhdan, Russkaia arkhitketura kontsa XIX—nachala XX veka (Russian Architecture of the End of the 19th Century and the Beginning of the 20th), Moscow: Izd-vo “Nauka,” 1971

Brumfield, William Craft, A History of Russian Architecture, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993

Brumfield, William Craft, and Blair A.Ruble, Russian Housing in the Modern Age: Design and Social History, Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, and Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993

Cohen, Jean Louis, Le Corbusier et la mystique de l’URSS: Théories pour Moscou, 1928–1936, Brussels: Mardaga, 1987; as Le Corbusier and the Mystique of the USS R: Theories and Pro jects for Moscow, 1928–1936, translated by Kenneth Hylton, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991

Cooke, Catherine, Russian Avant-Garde Theories of Art, Architecture, and the City, London: Academy Editions, 1995

Ginzburg, Moisei Iakovlevich, Stil i epokha, Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe Izdatelstvo, 1924; as Style and Epoch, translated by Anatole Senkevitch, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1982

Khan-Magomedov, Selim O., Alexandr Vesnin and Russian Constructivism, New York: Rizzoli, 1986

Khan-Magomedov, Selim O., Pioneers of Soviet Architecture: The Search for New Solutions in the 1920s and 1930s, translated by Alexander Lieven, edited by Catherine Cooke, New York: Rizzoli, and London: Thames and Hudson, 1987

Khazanova, V.E., Sovetskaia arkhitektura pervykh let Oktiabria, 1917–1925 gg. (Soviet Architecture of the First Years of October, 1917–1925), Moscow: Nauka, 1970

Kopp, Anatole, Constructivist Architecture in the USSR, London: Academy Editions, and New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985

Lissitzky, El, Russland: Die Rekonstruktion der Architectur in der Sowjetunion, Vienna: Schroll, 1930; as Russia: An Architecture for World Revolution, translated by Eric Dluhosch, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London: MIT Press, 1970

Lodder, Christina, Russian Constructivism, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1983 Paperny, Vladimir, Kultura “Dva”: Sovetskoya arkhitekura, 1932–1954, Ann Arbor, Michigan: Ardis, 1984

Riabushin, A.V., and N.I.Smolina, Landmarks of Soviet Architecture, 1917–1991, New York: Rizzoli, 1992

Senkevitch, Anatole, Soviet Architecture 1917–1962: A Bibliographical Guide to Source Material, Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1974 Tupitsyn, Margarita, El Lissitzky: Beyond the Abstract Cabinet, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1999

Pioneers of Soviet Architecture: The Search for New Solutions in the 1920s and 1930s

Архитектура ленинградского авангарда

Конструктивизм

Конструктивизм без берегов. Исследования и этюды о русском авангарде

ИНХУК и ранний конструктивизм

Москва: архитектура советского модернизма. 1955–1991. Справочник-путеводитель |

| |

|

|