| ALL |

|

SOVIET ARCHITECTURE

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

Before World War I architecture in Russia reflected the same influences as we have

already noted elsewhere: National Romanticism. Art Nouveau, and a vibrant avantgarde. The October Revolution in 1917, however. irrevocably changed the cultural

as well as the political scene in Russia. National Romanticism and Art Nouveau

faded away and members of the Russian avant-garde allied their program of cultural transformation with the political program of the revolution. Designers put

their talent to work in the service of the Soviet state.

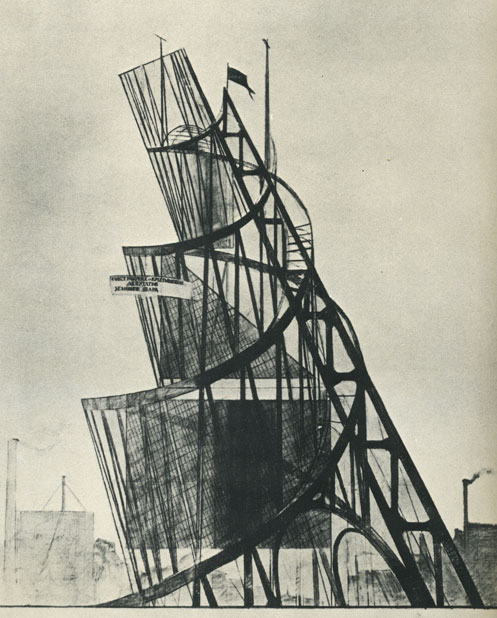

Vladimir Tatlin and Constructivism

In 1919 Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953) proposed a Monument to the Third International that would both represent and facilitate the agencies of the revolution. Over 400 meters tall, Tatlin's model invited comparison with the Eiffel

Tower and other great engineering monuments of the nineteenth century. The combination of an inclined spine thrusting up through a spiralling latticework created a

dynamic composition. Three volumes -a cube, a pyramid, and a cylinder-set

within the open skeletal frame housed various agencies of the Third International.

Each volume was to rotate at a different speed designed to coincide with the frequency of the scheduled meetings for each agency: once a year for the legislative,

once a month for the administrative, and once a day for the information agency,

This transparent, kinetic composition, the antithesis of the solid. earthbound forms

of tradition, illustrates the formal character and the spirit of what, in the 1920s,

came to be called Constructivist architecture.

Constructivist architects sought to extend the formal language of abstract art to

the design of buildings. The buildings were "constructed" conceptually as well as

physically of the basic visual elements such as lines, planes, and volumes. This

new syntax of form, according to the Constructivists, was grounded in A scientific

understanding of human perception and social organisation. For Russian architects.

a potent combination of political revolution, material progress, and aesthetic innovation held the promise of a new universe of possibilities. By developing a new formal language for design, architects believed they were answering the revolution's call to bring into existence a new Communist society.

However, Constructivism was more than simply a response to the revolution.

Convinced that the built environment influences everyone who inhabits it. Constructivist architects believed they could affect the development of the new society.

In the design of buildings and spaces (both public and private). architects could

encode the basic elements of the new social order and vividly convey

to all members of society the enormity of the political, economic, and social changes

unleashed by the October Revolution.

ASNOVA and OSA

Enthusiasm does not guarantee consensus,

however; Constructivism hardly constituted a uniform movement. In the early 1920s different orientations emerged within

Soviet architecture and crystallised around several professional societies. In 1923

the Association of New Architects (identified by the Russian acronym ASNOVA)

was formed, followed shortly by another group, the Union of Contemporary Architects (OSA). Both groups emphatically rejected the notion that traditional (now

labeled bourgeois) forms could give proper shape to socialist culture, but they differed over the relative weight to give expressive versus functional concerns.

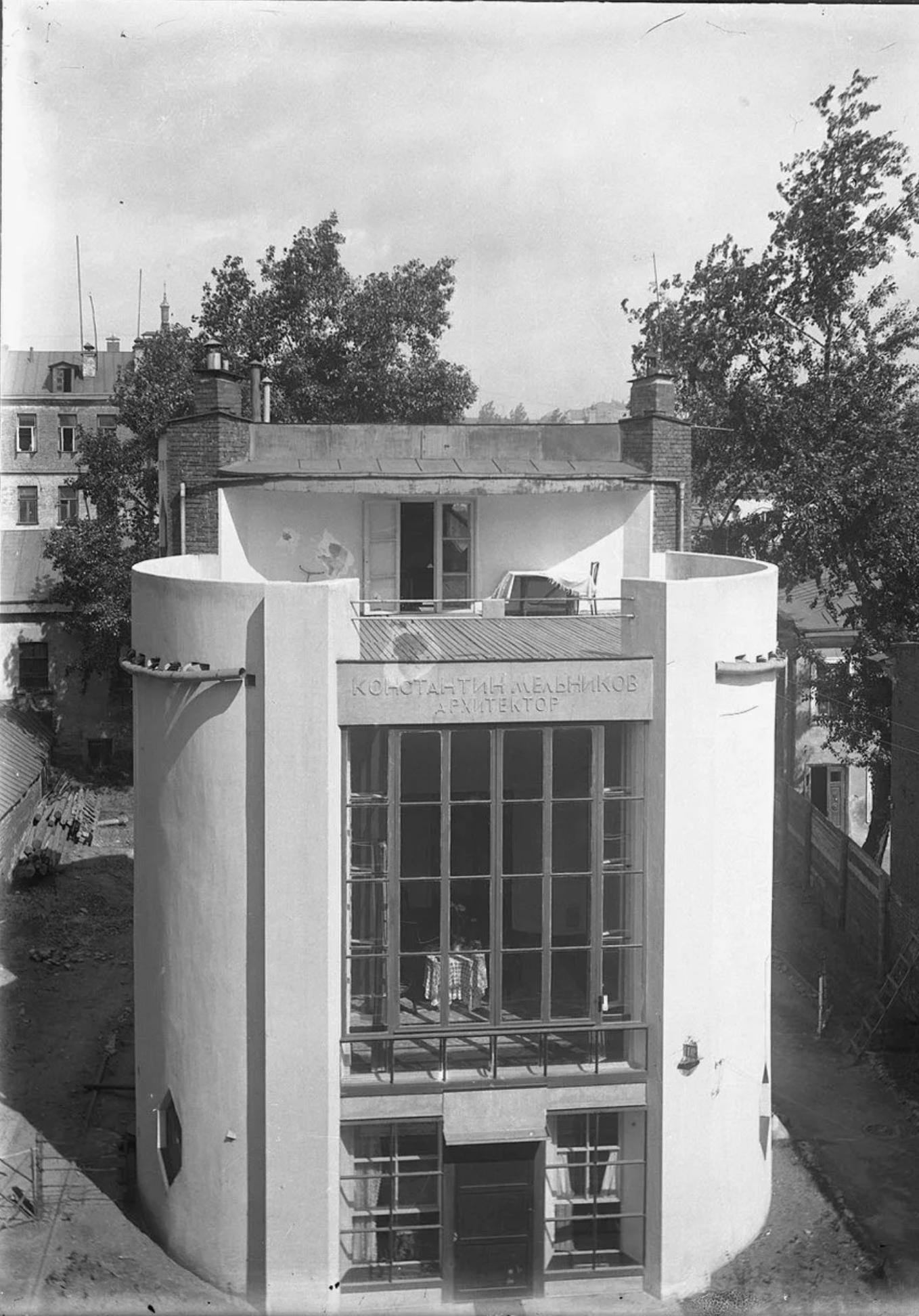

Konstantin Melnikov (1890-1974) was a prominent member of the ASNOVA

group. He achieved international success with his design for the Soviet Pavilion at

the 1925 "Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industries Modernes" in

Paris which contrasted sharply with the Art Deco style characteristic of other fair

pavilions. Between 1927 and 1929 he built six workers' clubs in Moscow. The

workers' club was an important building type; it was conceived as a center-

literally a "social condenser" for the formation of the new proletarian culture of Communism. For the Rusakov Workers' Club in Moscow, Melnikov allowed the blocks

of auditorium seating inside to project through the front of the building so that the

building reads as a sculpturesque composition of solids and voids. He

also provided a system of moveable partitions that allows the interior spaces to be

reconfigured in a variety of ways.

Moisei Ginzburg (1892-1946), one of

the leading figures of the OSA group,

was responsible, together with Ignatii

Milinis (1899-1974), for the design of the

Narkomfin Communal House in Moscow,

erected as housing for dependents of the

Russian Ministry of Finance.

Ginzburg conceived this project as prototypical Communal House (Dom Kommuna).

In the Constructivist vision,

communal housing would serve as the

incubator of the new socialist society and

facilitate the transition from bourgeois to

Communist conception of personal and

social space. The Narkomfin included a

communal kitchen. dining and laundry

facilities, and a gymnasium and library

(a communal childcare center was projected but never built).

Accommodation for 200 households in A variety of configurations

was provided. As an acknowledgment of the transitional state of

Russian society, a handful of Narkomfin units included small

kitchens to satisfy traditional conceptions of private family life.

Like Grete Schütte-Lihotzky's work in Frankfurt (see fig. 2.38),

OSA designers planned these kitchens as small, functional work-

stations. With its long horizontal bands of windows, flat roof. and

slender pilots, the design of the Narkomtin reflected the impact

of Le Corbusier's work in Russia.

VOPRA and Socialist Realism

The contrast between the expressive plasticity of Melnikov's

Rusakov Workers' Club and the lean, almost puritanical severity

of the Narkomfin design is indicative of the respective orientations of the ASNOVA and OSA groups. In 1929, however, a new association, the

All-Union Society of Proletarian Architects (VOPRA), was founded signalling a

new direction on the debates concerning revolutionary architecture. VOPRA began

to undermine the position of both ASNOVA and OSA architects, charging them

with ignoring the real conditions of Soviet society in favor of exercises in abstract

formalism. In Soviet terms, formalism was a feature of bourgeois art that reinforced

the distinction between popular and elite cultures. The VOPRA attacks paralleled

similar criticism against the experiments of the avant-garde in literature and art. In

the early 1930s, the Communist Party began to reformulate its approach to artistic

activity. In 1932 all independent groups were suppressed and the memberships of

various cultural organisations were combined into unions representing the interests

of each discipline. By 1934 the regime had adopted socialist realism as the official

cultural policy.

Defining socialist realism in architectural terms is not as easy as it is for other

visual arts because one can attach various meanings to the word realism in build-

ing. However, the issue of legibility is central to the socialist realist view of design.

One party edict stated: "In its search for an appropriate style, Soviet architecture

must strive for realistic criteria

for clarity and precision in images, which must be

easily comprehensible by and accessible to the masses." While projects like Tatlin's

Monument to the Third International were impractical given the economic and

technological state of the Soviet Union at the time, ultimately it was the pursuit of a

novel language of form based on abstraction rather than tradition that doomed the

Constructivist vision. In Stalin's Russia, to be avant-garde literally in front of the

mass audience was to court danger.

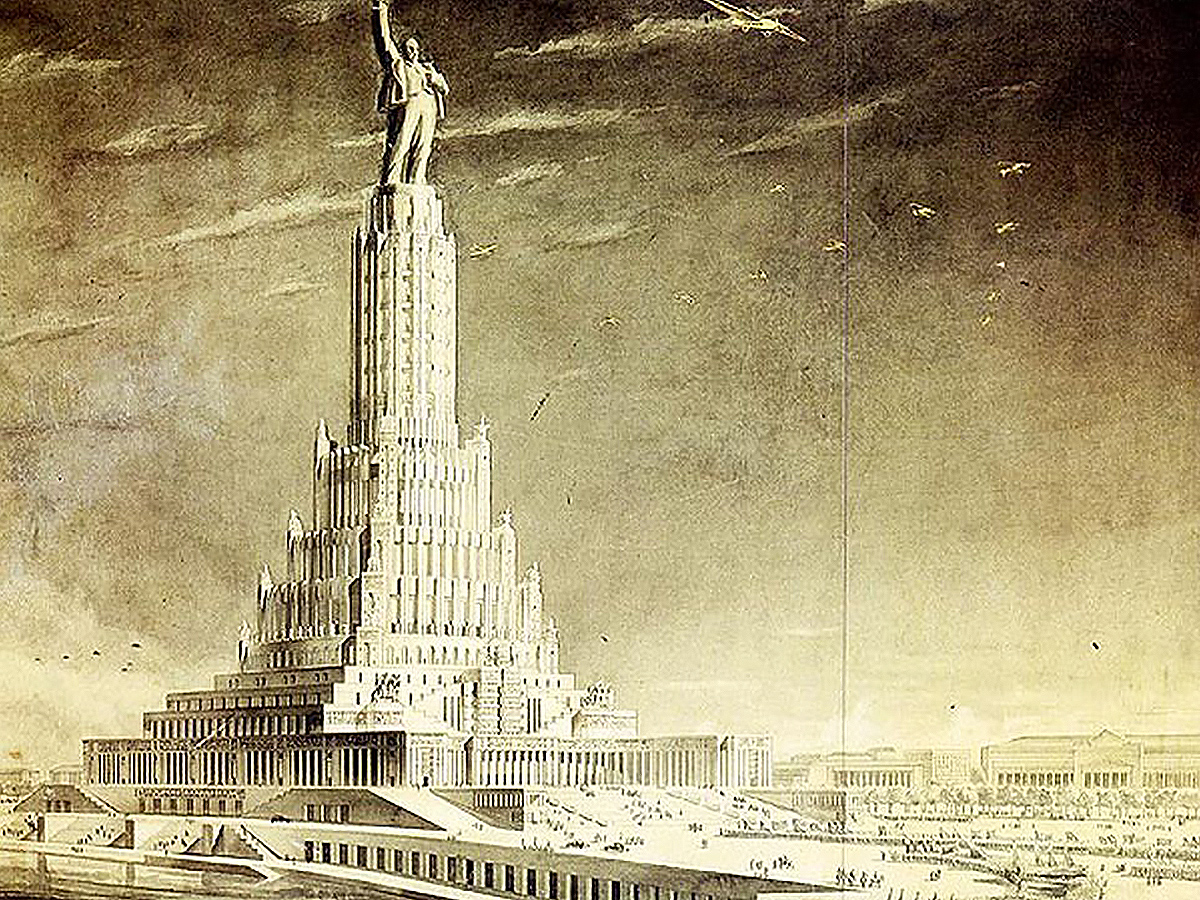

In 1931 an international design competition was announced for the Palace of the

Soviets in Moscow. The program called for meeting halls and offices for various

state agencies and identified the projected building as the preeminent architectural

symbol of the Soviet Union. The competition progressed through a series of rounds

and attracted entries from around the world. Many Constructivist architects submit-

ted proposals and the entries included a broad spectrum of traditional and modern

designs. Finally, in 1934 a team headed by Boris lofan (1891-1976) was awarded

the prize. The result influenced the development of Russian architecture for

decades.

lofan's enormous tower had the setback silhouette of an American skyscraper

which, by then, had become an instantly recognisable image of modernity. But

lofan's palace would never be mistaken for

capitalist office building: a statue of

Lenin over one hundred meters tall crowned the design and brought the total height

of the tower to more than four hundred meters, lofan rejected the Constructivist

language of form and relied on the traditional elements of monumentality such as

mass, symmetry, and axiality for effect. The vivid contrast between Tatlin's Monument to the Third International and lofan's Palace of the Soviets reveals the trajectory of political architecture in Russia.

Russian modernists, however, continued to enter major architectural competitions. The 1934 competition for the People's Commissariat for Heavy Industry

Headquarters (NKTP) in Moscow included a range of Constructivist entries. In his

proposal, Melnikov moved away from the more abstract forms characteristic of his

earlier work and transformed machine parts into giant architectural elements which

he combined with enormous figural sculpture (fig. 4.15). But his efforts to match the

epic scale and popular iconography of the Palace of the Soviets were no more succossful in gaining official support than the bold abstractions submitted by other

Constructivists, Ultimately, socialist realism in architecture was equated with the

application of classical models in the service of proletarian society. The leaders of

the recently constituted Union of Soviet Architects explicitly identified the classical heritage of

Greco-Roman antiquity and the Renaissance as the

appropriate model for Soviet architecture.

Stations designed for the Moscow subway

system provided a vivid demonstration of this

new design doctrine of palaces for the people. The

new underground system was an important part of

the modernisation program for the city; the first

completed stations date to the mid-1930s and

work continued for decades. The imposing Doric

columns of the Kurskaya metro station's central

hall, opened in 1949, transform this transit facility

into a patriotic shrine. Like a cult figure,

the statue of Stalin dominates the space and the

words of a new national anthem are inscribed on

the colonnade. The decorative programs of other stations celebrated Russian military and industrial achievements.

The USSR

Soviet architecture in the immediate postwar years followed a different path than design in the

West. The Moscow State University, for example, demonstrates a

very different solution to the problem of housing an academic institution. Rather than conceived as a

group of buildings, the university

was planned as a single, enormous

structure. The university

building was one of eight such

towers (of which seven were ultimately built) to be erected at key

points around the city, There is no strict relationship between architectural type

and functional program for these towers and they served a variety of purposes

including government offices, hotels, and apartments. According to Soviet planning

ideology of the late 1940s and early 1950s, the dispersal of tall buildings across the

city would distinguish Moscow, as a model Communist city, from the concentration

of skyscrapers in the urban center characteristic of Western capitalist cities. The site

atop the Lenin Hills overlooking the city provides the university with an imposing

presence on the city's skyline. but the ornate setback tower appears anachronistic

in the context of postwar design. The undecorated glass box characteristic of American skyscrapers in the 1950s represents the wedding of the formal and tectonic

preferences of modern architects with the concerns of real-estate interests for maximizing the profitability of land in the urban center. However, neither the

autonomous aesthetic preferences of the design profession nor a concern for profit

were factors in Soviet architecture during the Stalinist era. The Moscow State University reflects the continued significance of Boris loan's prizewinning design for

the Palace of the Soviets as a model for Russian architects (see page 102). It was not

until after Stalin's death in 1953 that Russian architects could begin to reconsider

the premises of socialist realism and explore alternative design strategies to promote the modernisation of the Soviet Union.

Dennis P. Doordan. Twentieth-century Architecture. H.N. Abrams., 2002. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1919-1920, a monument to the Third International, Vladimir Tatlin |

| |

|

| |

, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS.jpeg) |

| |

1923, Palace of Labor (Third prize, competition), Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS.jpeg) |

| |

1924, Pravda Newspaper Building (unbuilt), Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925–1927, the Izvestiia Building, Moscow, RUSSIA, Grigory Barkhin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1926, Leningrad Textile Complex, Leningrad, RUSSIA, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1926–1927, Bakhmetevsky Bus Garage, Moscow, RUSSIA, Konstantin Melnikov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927–1928, the Rusakov Club, Moscow, RUSSIA, Konstantin Melnikov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

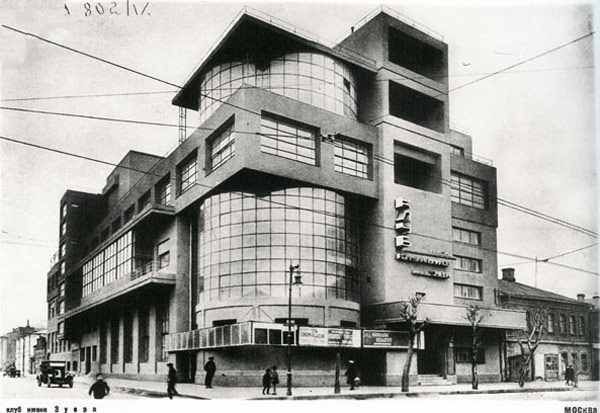

1927–1929, the Zuev Workers’ Club, Moscow, RUSSIA, Ilya Golosov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927, MELNIKOV HOUSE, Moscow, RUSSIA, Konstantin Melnikov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928, Food Factory #1, MOSCOW, USSR, Alexey Meshkov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928–1930, the apartment housefor the People’s Commissariat of Finance, Moscow, RUSSIA, Moisei Ginzburg

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928-1935, Tsentrosoiuz Building, Moscow, RUSSIA, Le Corbusier |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928-1940, Lenin State Library, Moscow, RUSSIA, Vladimir Shchuko, V. Gelfreikh |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1929, Mostorg Department Store, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1930, Student housing of Communist University of the National Minorities of the West, Moscow, USSR, G. Dankman |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1931–1937, the Likhachev Palace of Culture, Moscow, RUSSIA, Vesnin brothers |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1933, Centrosoyus, Moscow, Russia, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1933–1935, Palace of the Soviets, Boris Iofan, Vladimir Gelfreikh, Vladimir Shchuko |

| |

|

| |

competition project, Konstantin Melnikov.jpeg) |

| |

1934, Narkomtiazh People's (Commissariat for Heavy Industry) competition project, Konstantin Melnikov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1934, Apartment house, Marx Prospekt, Moscow, RUSSIA, Ivan Zholtovskii |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1934, Society of Tsarist Political Prisoners Club,

Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1937, Proletarian Region Club,

Moscow, RUSSIA, Vesnin brothers |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1949, Kurskaya

metro station, central hall,

Moscow, RUSSIA, Grigorii

Zakharov and Zinaida

Chernysheva |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1949–1953, Moscow State University, Moscow, RUSSIA, Lev Rudnev, Pavel Abrosimov, Alexander Khriakov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1954, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Moscow, RUSSIA, M. Minkus, V. Gelfreikh |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1956, Luzhniki Stadium, Moscow, RUSSIA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1958-1961, Pioneers Palace, Moscow, RUSSIA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

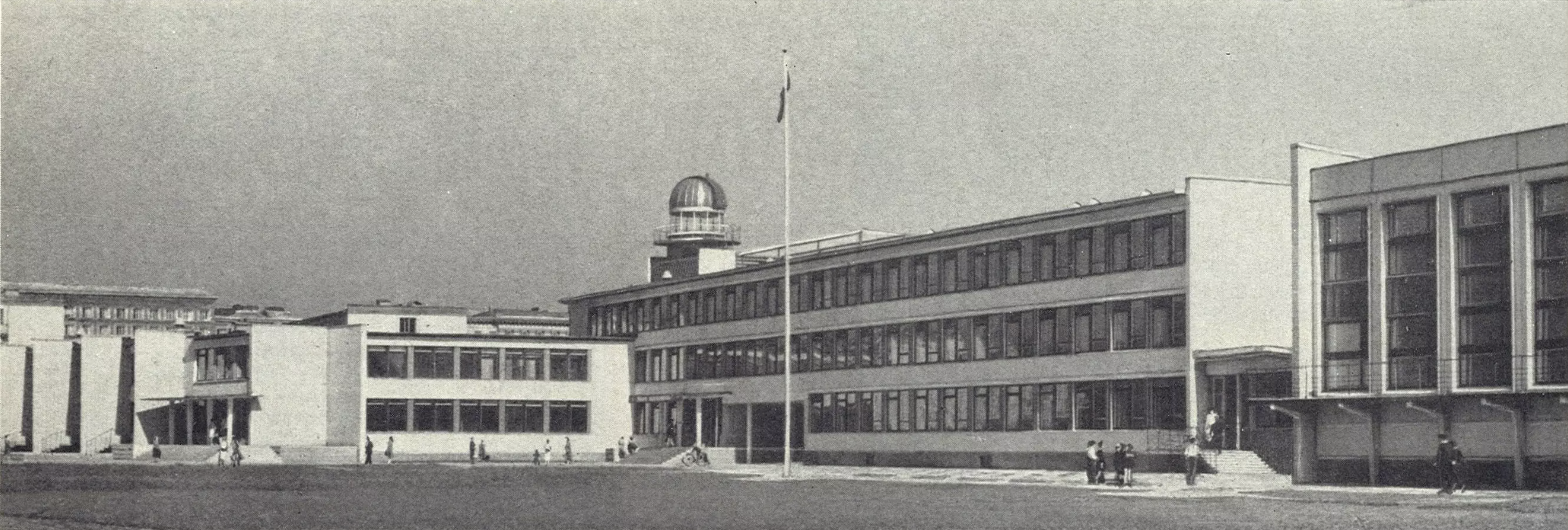

1958-1968, School #345, Leningrad, USSR |

| |

|

| |

.jpeg) |

| |

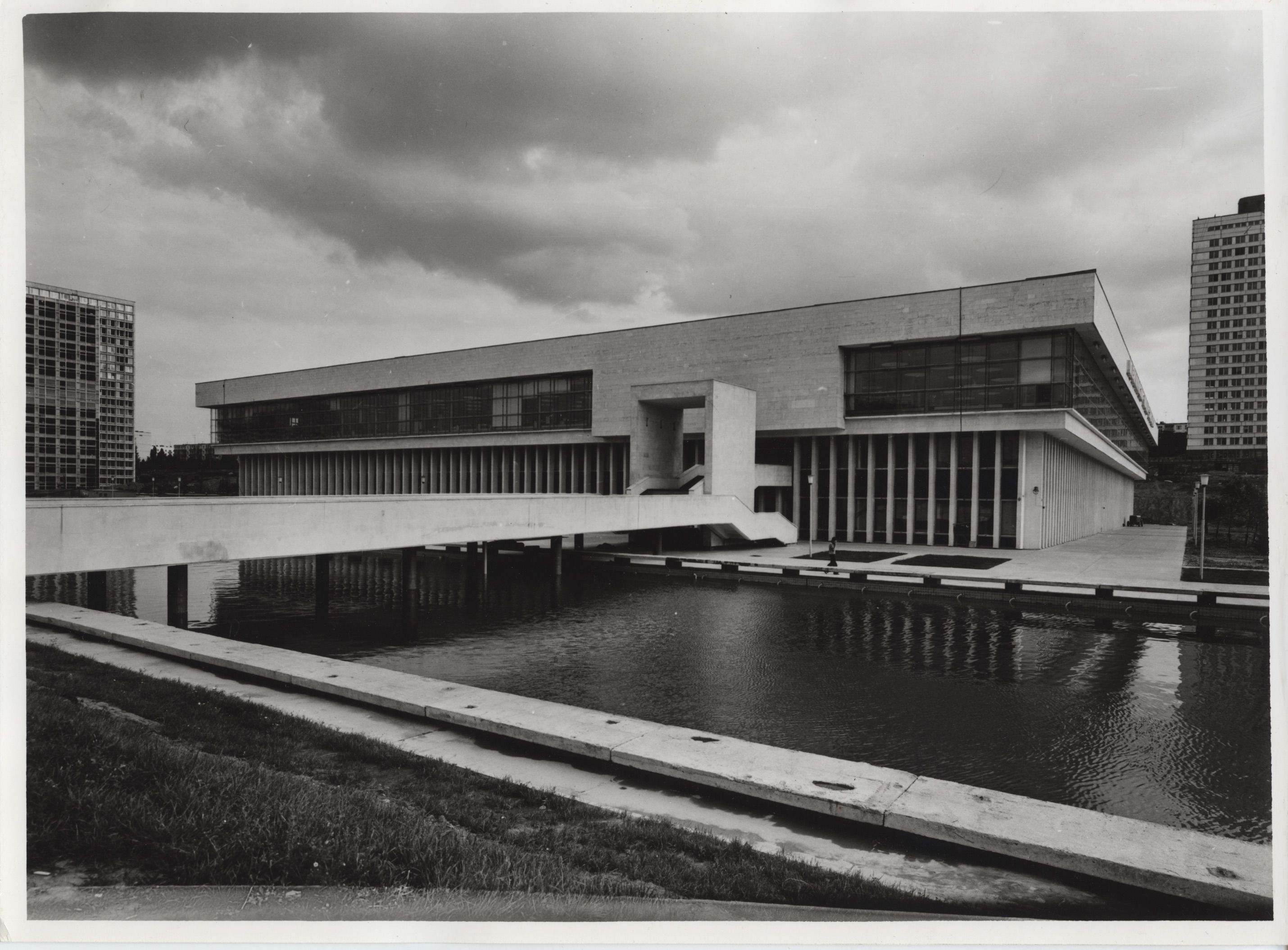

1959–1961, the Kremlin Palace of Congresses, Moscow, RUSSIA, Mikhail Posokhin (in collaboration with A. Mndoiants and others) |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

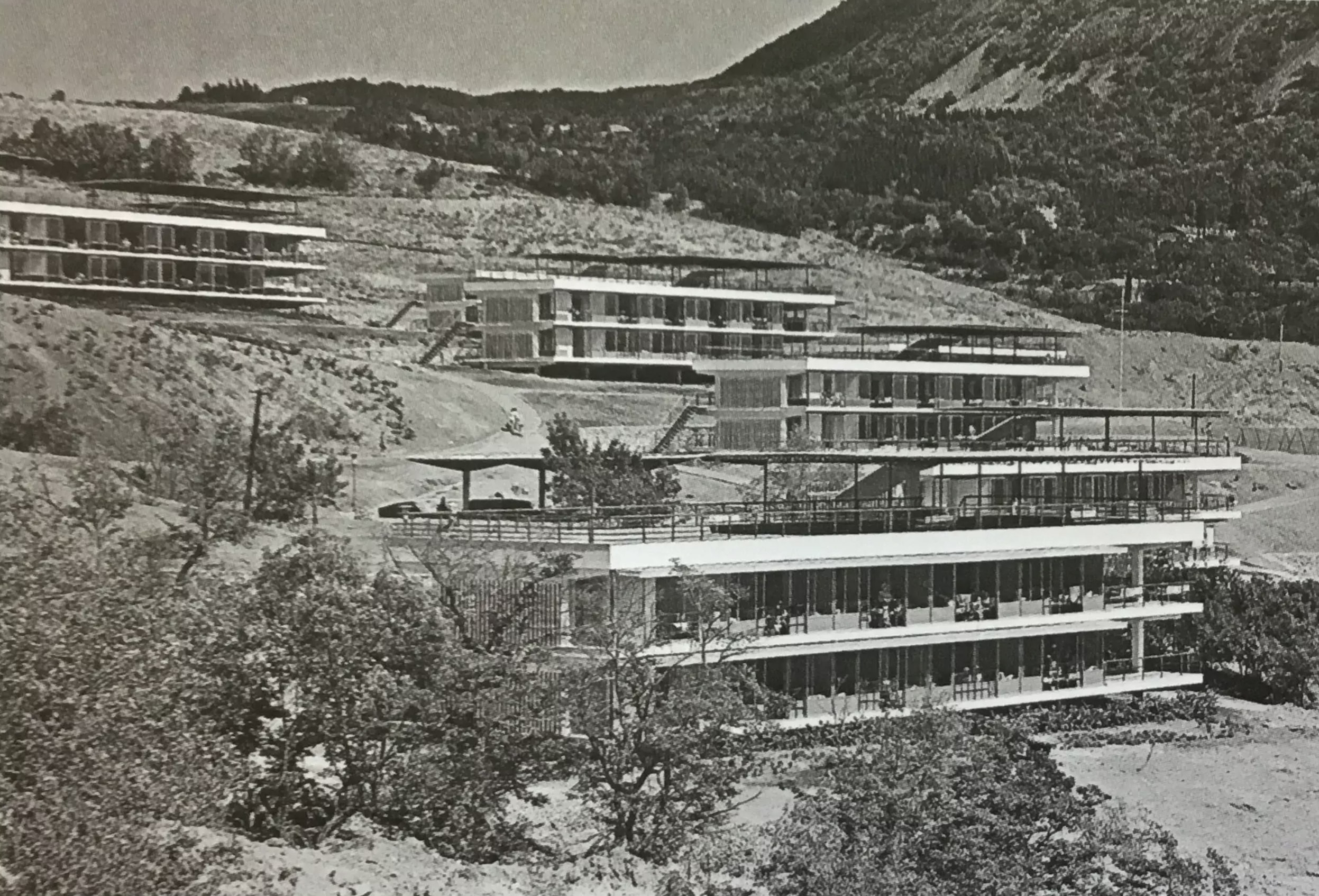

1959-1961, Artek, Crimea, RUSSIA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1962-1963, Prospekt Kalinina, Moscow, RUSSIA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1965-1971, Doma Aspirantov i Stazherov Mgu, Moscow, RUSSIA, N. Osterman |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1967, the Ostankino Television Tower, Moscow, RUSSIA, N.Nikitin, L.Batalov, and others |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1967-1974, Swan Residence, Moscow, RUSSIA, A. Meherson |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1971, National Research University of Electronic Technology, Zelonograd, RUSSIA, Novikov F. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1972, Ploschad Yunosti, Zelenograd, RUSSIA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1973,VINTITI, Moscow, RUSSIA, Y. Belopolsky, |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1973, Pulkovo Airport, Saint Petersburg, RUSSIA, Zhuk A. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1973-1990, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, RUSSIA, Y. Platonov |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1974, Инженерный корпус Министерства автомобильных дорог Грузии, Tbilisi, Georgia, Dzhalaganiya Z. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

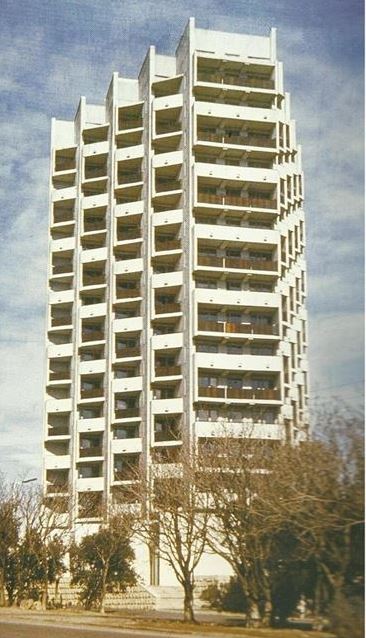

1975, Apartment block, Baku, Azerbaijan, Belokon A.N. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

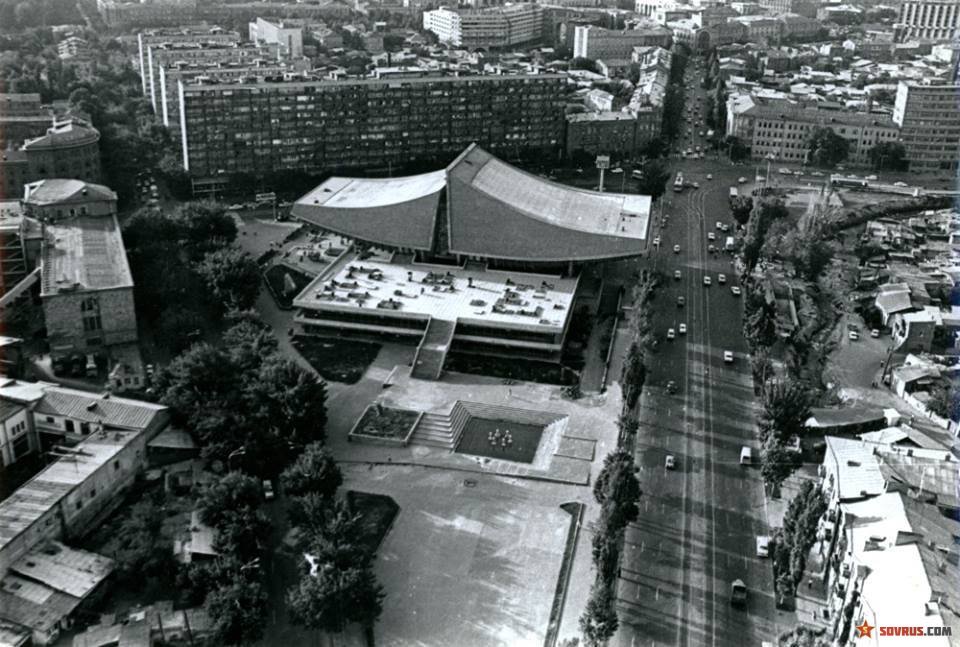

1975, Rossiya Cinema, Yerevan, Armenia, Tarhanyan A. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1975-1982, Severnoe Chertanovo, Moscow, RUSSIA, GROUP OF ARCHITECTS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1976-1988, Bioorganic Research Institute, Moscow, RUSSIA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

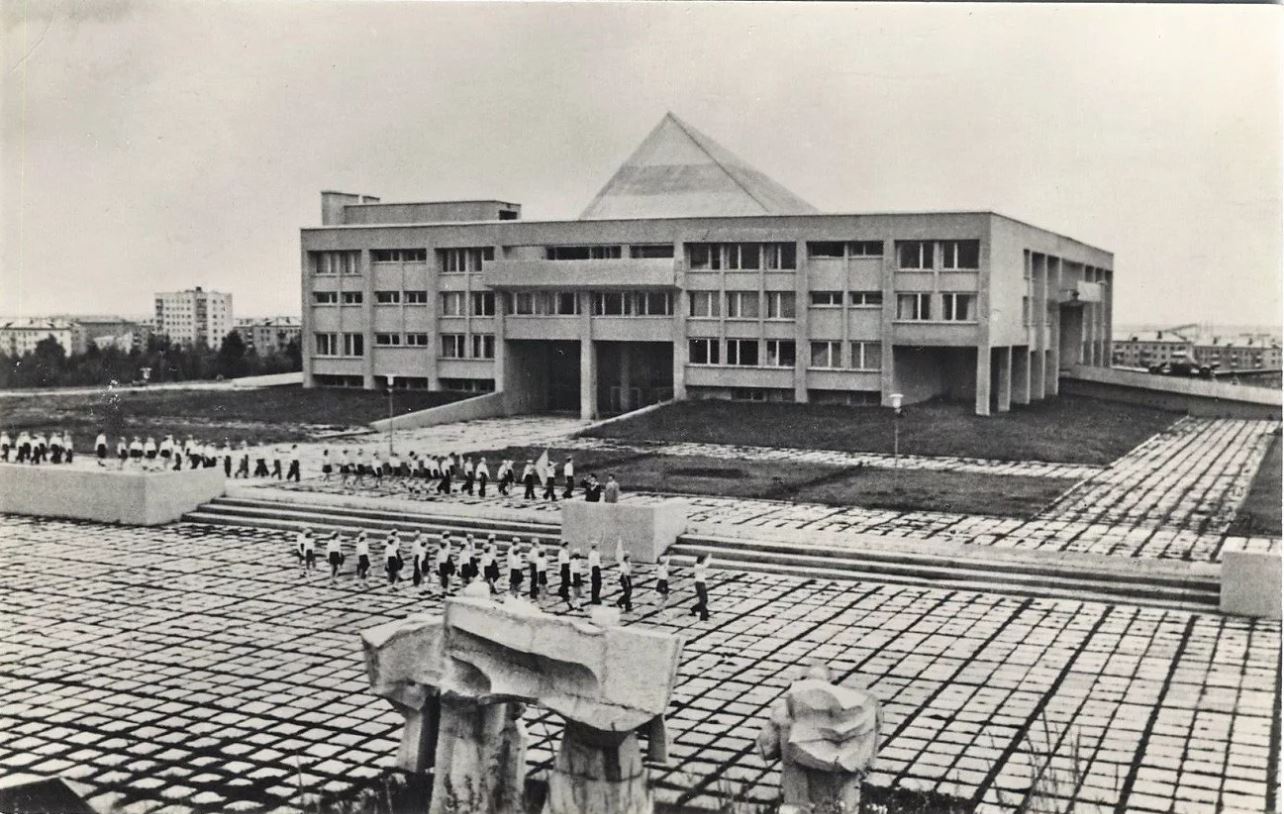

1977, Dvorec Pionerov, Kirov, RUSSIA, Gazerov. L. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1977, Dvorec Molodezhi, Yerevan, Armenia, Tarhanyan A. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

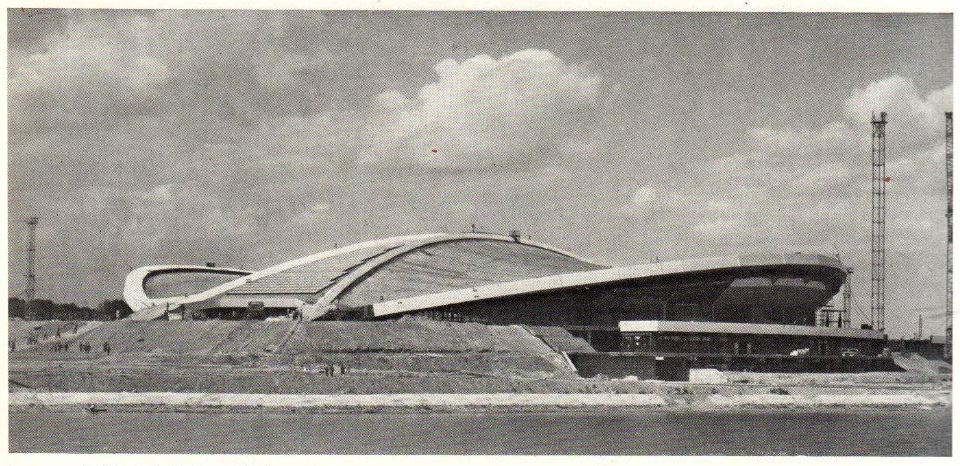

1980, Cycling Track, Moscow, RUSSIA, Voronina N. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1980, Olympic Village, Moscow, RUSSIA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1981-1987, The Sun Heliocomplex, Uzbekistan |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1986, House of Nuclear Workers, Moscow, RUSSIA, V. Voskresensky |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1987, CNII Cyber Institute, Leningrad, USSR, S. Savin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

GINZBURG, MOISEI

GOLOSOV, ILYA

LEONIDOV, IVAN ILICH

MELNIKOV, KONSTANTIN STEPANOVICH

VESNIN, ALEXANDER, LEONID VESNIN, AND VIKTOR VESNIN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1923, Palace of Labor (Third prize, competition), Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

1924, Pravda Newspaper Building (unbuilt), Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

1925–27, the Izvestiia Building, Moscow, RUSSIA, Grigory Barkhin |

| |

|

| |

1927, MELNIKOV HOUSE, MOSCOW, RUSSIA, Konstantin Melnikov |

| |

|

| |

1929, GARAGE, MOSCOW, RUSSIA, Konstantin Melnikov |

| |

|

| |

1929, RUSAKOV CURTURE HOUSE, MOSCOW, RUSSIA, Konstantin Melnikov |

| |

|

| |

1929, Mostorg Department Store, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

1927–29, the Zuev Workers’ Club, Moscow, RUSSIA, Ilya Golosov |

| |

|

| |

1928, NARKOMFIN HOUSE, MOSCOW, RUSSIA, Moisei Ginzburg |

| |

|

| |

1933, Centrosoyus, Moscow, Russia, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1933–35, Palace of the Soviets, Boris Iofan, Vladimir Gelfreikh, Vladimir Shchuko |

| |

|

| |

1934, Society of Tsarist Political Prisoners Club, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

1937, Proletarian Region Club, Moscow, RUSSIA, VESNIN BROTHERS |

| |

|

| |

1949–53, Moscow State University, Moscow, RUSSIA, Lev Rudnev, Pavel Abrosimov, Alexander Khriakov |

| |

|

| |

1959–61, the Kremlin Palace of Congresses, Moscow, RUSSIA, Mikhail Posokhin (in collaboration with A. Mndoiants and others) |

| |

|

| |

1967, the Ostankino Television Tower, Moscow, RUSSIA, N.Nikitin, L.Batalov, and others |

| |

|

| |

1978–79, the Velotrek bicycle racing stadium, Moscow, RUSSIA, Natalia Voronina and others |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

Art Nouveau; Constructivism; Golosov, Ilya; Leonidov, Ivan Ilich; Melnikov, Konstantin; RUSSIA and USSR; Vesnin, Alexander, Leonid, and Viktor

FURTHER READING

Modern Russian architecture and particularly the early Soviet avantgarde have received considerable attention from Western scholars, as well as from Russians. The following list is a sample of some of the more prominent works.

Barkhin, M.G., et al. (editors), Mastera sovetskoi arkhitektury ob arkhitekture (Masters of Soviet Architecture on Architecture), 2 vols., Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1975

Bliznakov, Milka, “The Realization of Utopia: Western Technology and Soviet AvantGarde Architecture,” in Reshaping Russian Architecture: Western Technology, Utopian Dreams, edited by William C.Brumfield, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991

Borisova, Elena A., and Tatiana P.Kazhdan, Russkaia arkhitketura kontsa XIX—nachala XX veka (Russian Architecture of the End of the 19th Century and the Beginning of the 20th), Moscow: Izd-vo “Nauka,” 1971

Brumfield, William C., The Origins of Modernism in Russian Architecture, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991 ——, A History of Russian Architecture, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993

Cohen, Jean-Louis, Le Corbusier et la mystique de l’USSR, Brussels: Mardaga, 1987; as Le Corbusier and the Mystique of the USSR, translated by Kenneth Hylton, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1991

Cooke, Catherine, Russian Avant-Garde: Theories of Art, Architecture, and the City, London: Academy Editions, 1995

Ginzburg, Moisei IAkovlevich, Stil i epokha, Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe Izdatelstvo, 1924; as Style and Epoch, translated and edited by Anatole Senkevitch, Jr., Cambridge, Massachusetts: MITPress, 1982

Khan-Magomedov, Selim O., Pioneers of Soviet Architecture: The Search for New Solutions in the 1920s and 1930s, translated by Alexander Lieven, edited by Catherine Cooke, New York: Rizzoli, and London: Thames and Hudson, 1987

Khazanova, V.E., Sovetskaia arkhitektura pervykh let Oktiabria, 1917–1925 gg. (Soviet Architecture of the First Years of October, 1917–1925), Moscow: Nauka, 1970

Russian avant-garde

Lissitzky, El, Russland: Architektur für eine Weltrevolution, Berlin: Ullstein, 1965; as Russia: An Architecture for World Revolution, translated by Eric Dluhosch, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1970

Lodder, Christina, Russian Constructivism, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1983

Riabushin, A.V., and N.I. Smolina, Landmarks of Soviet Architecture, 1917–1991, New York: Rizzoli, 1992

Starr, S.Frederick, Melnikov: Solo Architect in a Mass Society, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978

Yaralov, Yurii Stepanovich, compiler, Zodchie Moskvy (Architects of Moscow), edited by S.M.Zemtsov, 2 vols., Moscow: Moskovskii Rabochii, 1988

Былинкин Н.П., А.М.Журавлев, И.В.Шишкина и др., Современная советская архитектура, Стройиздат, 1985

Хазанова В.Э., Советская архитектура первой пятилетки: проблемы города будущего

Хан-Магомедов С.О., Архитектура Запада. Мастера и течения, Стройиздат, 1972

Хан-Магомедов С. О., ВХУТЕМАС, Издательство Ладья, 1995

Хан-Магомедов С.О., Кривоарбатский переулок, 10

Хан-Магомедов С. О., Константин Мельников, Стройиздат, 1990

Хан-Магомедов С.О., Пионеры советского дизайна, Галарт, 1995

Хан-Магомедов С.О., Супрематизм и архитектура (проблемы формообразования)

История советской архитектуры

Москва: архитектура советского модернизма. 1955–1991. Справочник-путеводитель

Ленинград. Архитектура советского модернизма. 1955-1991. Справочник-путеводитель

«Пришел, увидел — побежден!» Советские и британские архитекторы в 1930–1960-е годы

Архитектура Дома Наркомфина вчера и сегодня |

| |

|

|