| ALL |

|

EXPRESSIONISM

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

The postimpressionist revolution in late 19th-century painting eventually brought the opposite of figurative representation, namely, Expressionism. If representation was no longer the main goal of art, the expression of one’s inner spiritual self offered itself as an alternative. In the first decade of the 20th century, this direction was taken primarily by German artists, most successfully by the two movements Der Blaue Reiter and Die Brücke. Painters such as Wassily Kandinsky and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner used art to express the soul and their emotional reactions to the modern era. Their paintings introduced a cryptic, abbreviated style to art. The origin of a design in the creator’s self and a drawing technique that was not concerned with exact figural representation were among the main impulses for Expressionist architecture.

Centered primarily in Germany and the Netherlands, Expressionist architects, just like their mainstream International Style colleagues, tried above all to cope with the industrial age. However, like their namesakes in painting, they attempted to express this age instead of representing it.

Apart from this artistic goal, Expressionist architecture also dealt with communal concepts. Immediately after World War I, the massive physical and human destruction that had been caused by the first large-scale mechanical warfare engendered an anti-industrial feeling. Industry had excelled in manufacturing death machines that resulted in utter destruction. Such a common enemy brought forth thoughts about fraternization, community, and democracy. Especially in Germany, the postwar reality was difficult to bear. The shock of having lost the war brought with it the feeling that an era had passed and that it was time to orchestrate the rebirth of communal life and the arts. With its propagation of exactly such goals, Expressionism offered a feasible way to cope with the problems of the early 1920s in Europe. Expressionism rejected the machine age as the foundation of artistic creation. In architecture, this came out as the opposition to design as conditioned only by utility, materials, construction, and economics. Instead, Expressionism advocated that political and artistic revolution were the same by transposing the social uprising into artistic activity.

Apart from the origin in painting, immediate stylistic sources of Expressionism in architecture are found in Art Nouveau and other late 19th-century attempts at renewal, especially in the work of Hendrik Petrus Berlage, Frank Lloyd Wright, and Otto Wagner. Art Nouveau (Jugendstil) was particularly favored because it had rejected industrial construction methods and displayed a rather romantic longing in its naturalistic decorative structures. However, Expressionist architects had quite an open attitude toward the past. The styles in which all the arts had combined to produce decorated forms were preferred sources for inspiration. From Egypt came the concepts of cave and tower. Gothic architecture provided examples for the social and communal purposes of architecture and showed the triumph of expression over function. Far Eastern architecture was an important source because it combined architectural and sculptural forms and because of the mystical doctrines that informed this architecture.

The particular mind-set of Expressionist architects was also influenced by literary and philosophical sources, found primarily in Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. From Nietzsche came the admonition to let primitive instincts, not conscious self-control, determine artistic creations, whereas Kierkegaard emphasized the psychological background for this style in the spiritual searching and feeling of despair that were produced through the material instability.

The most significant heritage of Expressionism is that it attempted to solve the problems of the world through mainly symbolic architecture. Architects felt that they had to act on behalf of society and believed that they had to force people to realize their happiness through building. In those years, the spiritual realm was very far removed from reality. Expressionist architecture had a strong Utopian urge. It was the search for a new reality, a new sense of life, and a new ethics of humanity. Many of the projects are indeed on a cosmic scale. This stemmed primarily from architects aiming to create their designs directly from their own visions. They let their hands draw the designs automatically and tried to exclude the mind from participating in the sketching. Their designs came out of an uncontrollable inner necessity and an inner spiritual life. The architects felt themselves to be the instruments of an absolute, metaphysical will and saw their task as transforming this spirit into reality. They wanted to achieve the direct transformation of consciousness into pure activity and did not pay much consideration to the objects that resulted from this. Theirs was an architecture that appealed to the intellect through feeling. With such practices, Expressionist architects found their modernity independently, unlike the International Style, which found its modernity through representation. Like the International Style, Expressionism avoided the literal imitation of traditional styles, but it also focused on expressing ideas. The Expressionist conception of the building was that of a total work of art that would present an aesthetic unity and thus become communal art. In this sense, architecture was spiritual.

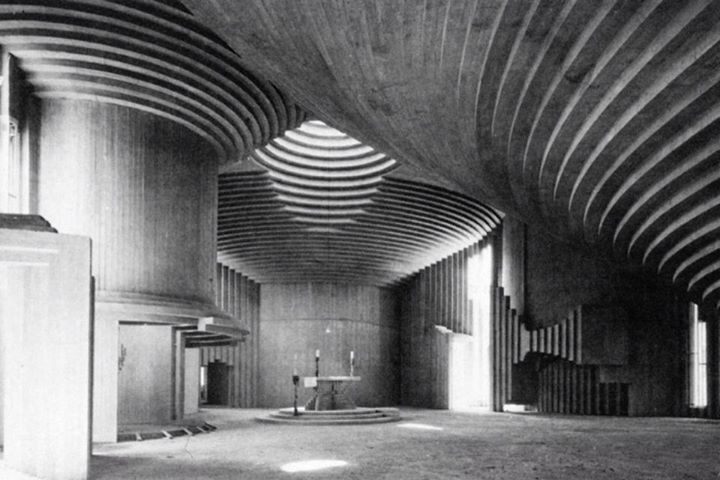

In terms of form, Expressionist architects had a preference for cavelike interiors and towerlike exteriors. Inside their buildings, one felt enveloped not by walls and ceiling but by an encompassing membrane. Interiors felt physically oppressing on the inhabitant, who had to use sight, touch, and other synesthetic senses to understand his or her whereabouts. The theme of the cave was articulated in the exterior through a tectonic treatment of the building surfaces. The tower shape was articulated mostly by fashioning buildings as crowns, be they in the city or on the top of mountains.

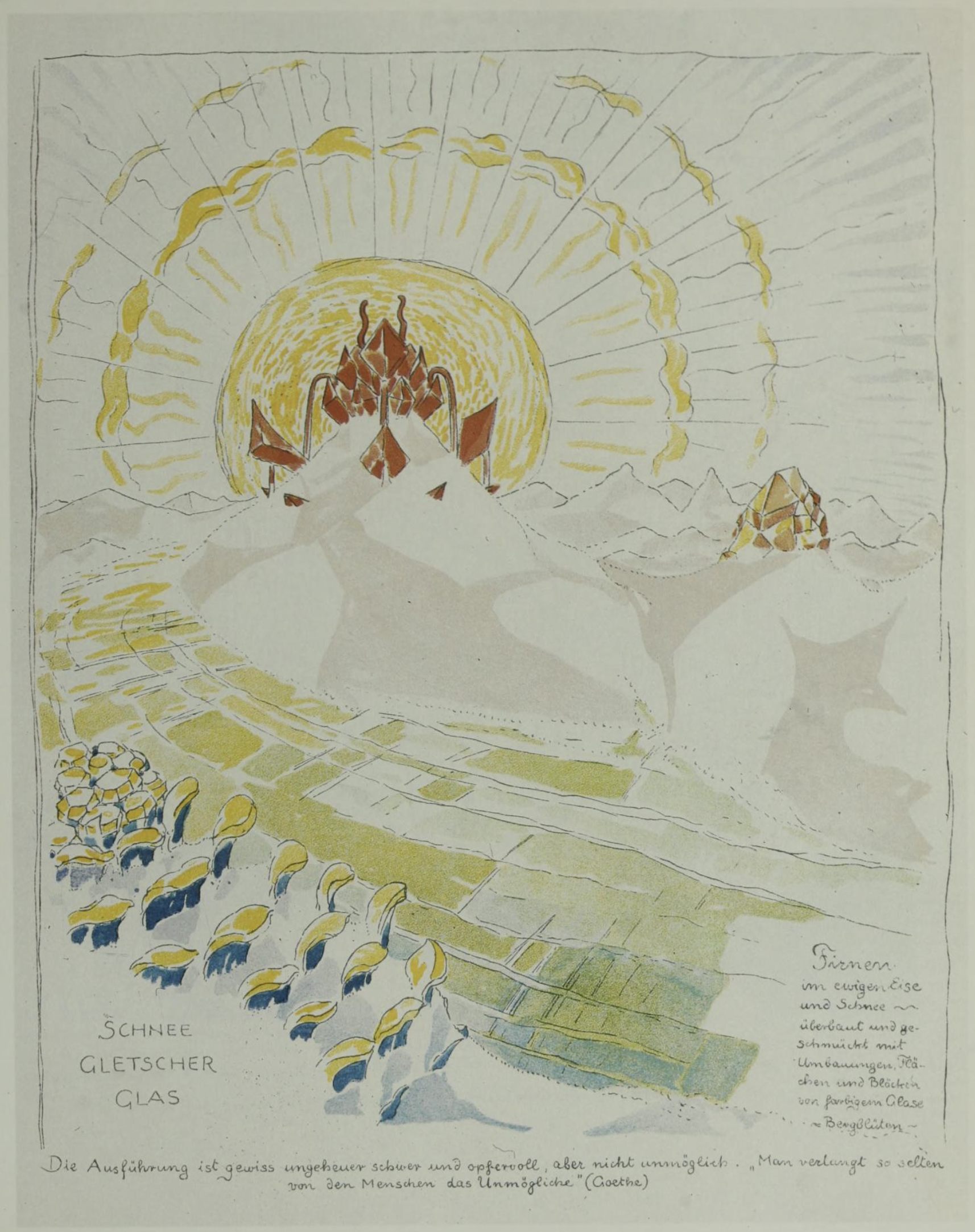

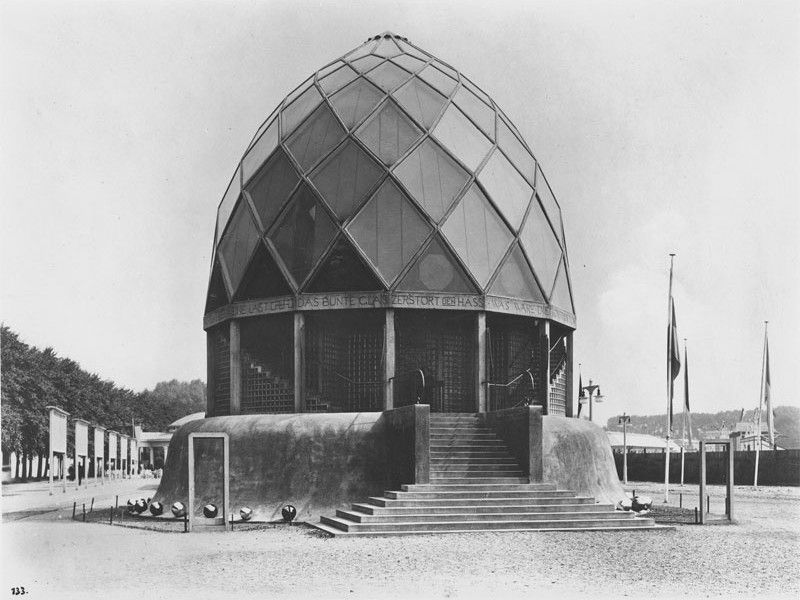

In Germany, Paul Scheerbart instigated the preference for glass and crystals among Expressionist architects. Scheerbart can best be described as one of the fathers of science fiction in Germany. Apart from providing technical information in his book Glasarchitekt ur (1914), Scheerbart also promoted glass building for its generation of a new morality. Glass stood for brighter awareness, clearer determination, and utter gentleness. It represented the search for light and higher truth—the clarification of the soul—and can generally serve as a social catalyst. Glass buildings can function as shelter as well as extend garden architecture. This transparent material forces the users to continually relate to their environment, both the natural and the cosmic one. Glass buildings resemble states of emotion and suggest infinite space. In its mineral form, as crystal, glass became a symbol for the new life. Thus, glass and crystal forms presented the milieu that would give birth to the new culture.

Many Expressionist architects gave glass a special role in their designs. Bruno Taut, the organizer and indefatigable theoretician of Expressionism, was particularly taken with Scheerbart’s ideas. He accepted the purifying potential of glass and crystal in his designs. These were especially notable in the Glass Pavilion he designed in 1914 for the glass industry at the Cologne Werkbund exhibition. There, Taut added a cosmological component. Glass was used as the material that enabled the reconciliation of mind and matter. The Glass Pavilion created primarily an experience for the user in the form of a purification ritual. It was intended to introduce a lighter building method and high-light the effects of glass to architecture. It is assembled from a centralized building with an addition at the back. The pavilion consists of a geodesic dome on a concrete base. Prism glass in reinforced-concrete frames was used for both the walls and the stair treads leading up to the glass hall. This is covered by a crystal-shaped dome assembled from reinforced-concrete ribs and colored-glass panels resting on prism glass. Visitors took a predetermined path that ultimately led them to the cascade room on the lower level. Water flowed down glass steps and terminated in a recess in which pictures from a kaleidoscope were projected. The procession through this pavilion was characterized by seductive anticipation and an increasingly intense experience of space. In Taut’s later Alpine Architecture (1919), glass was used on an increased scale by designing glass pavilions on mountaintops.

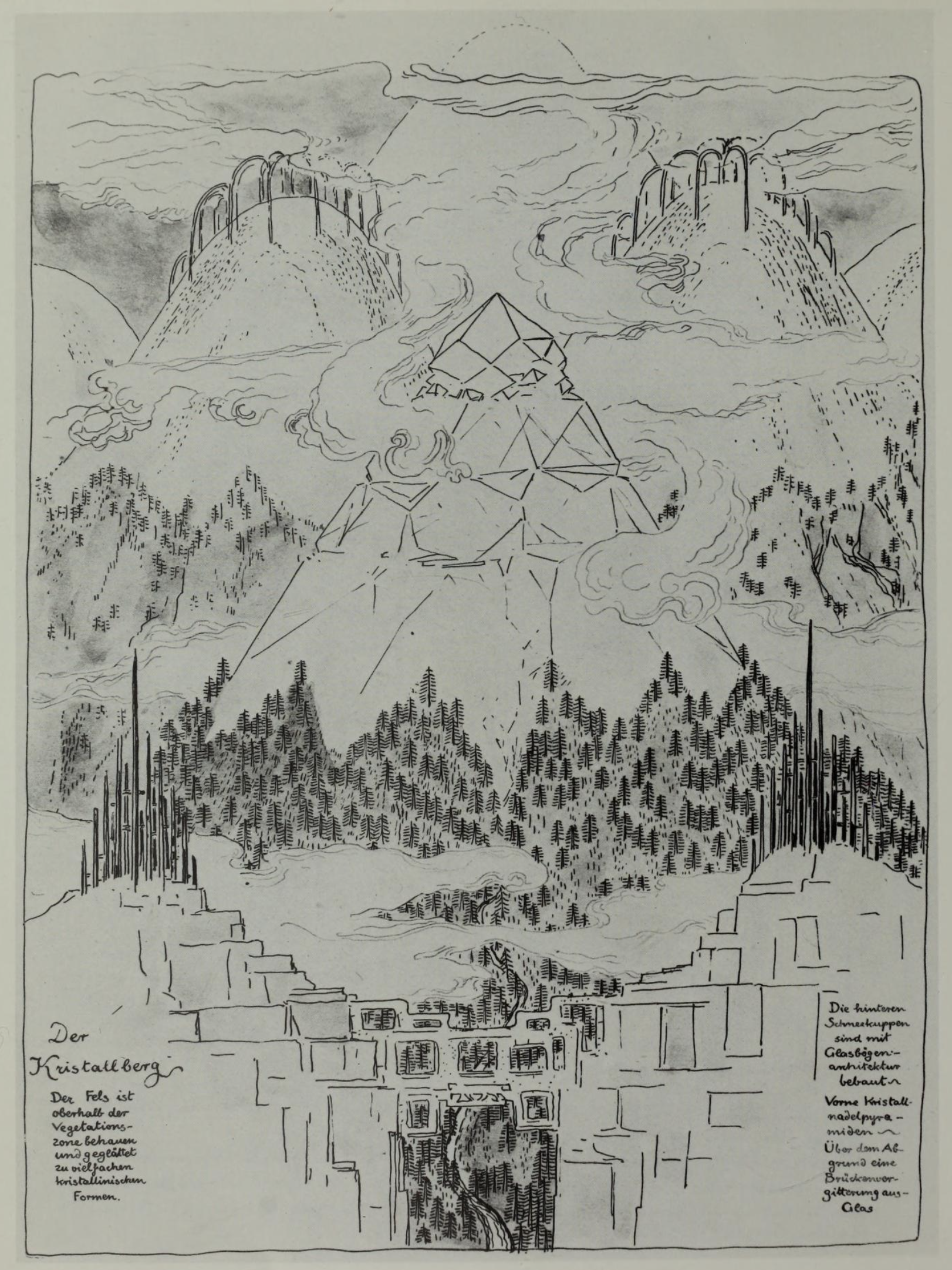

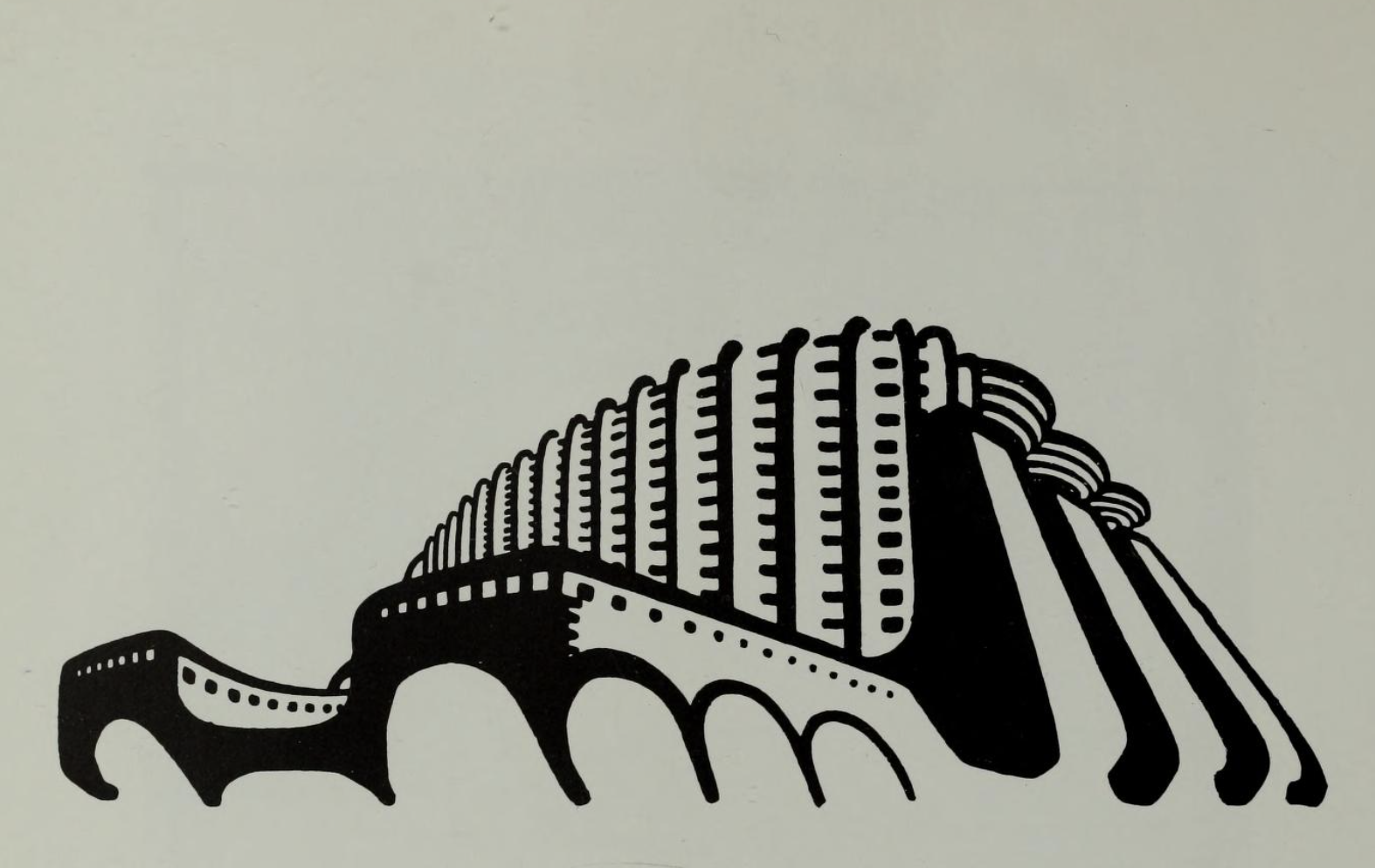

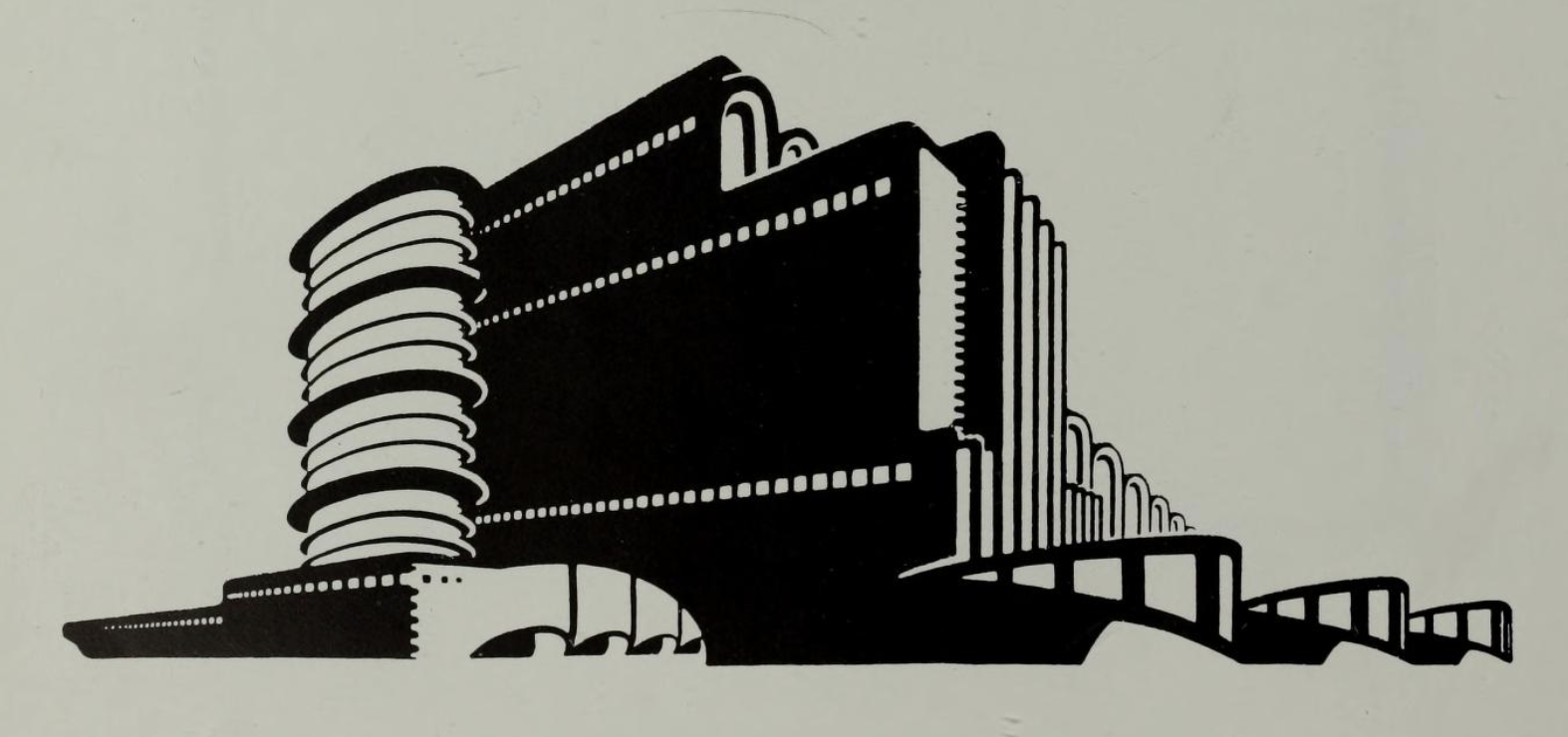

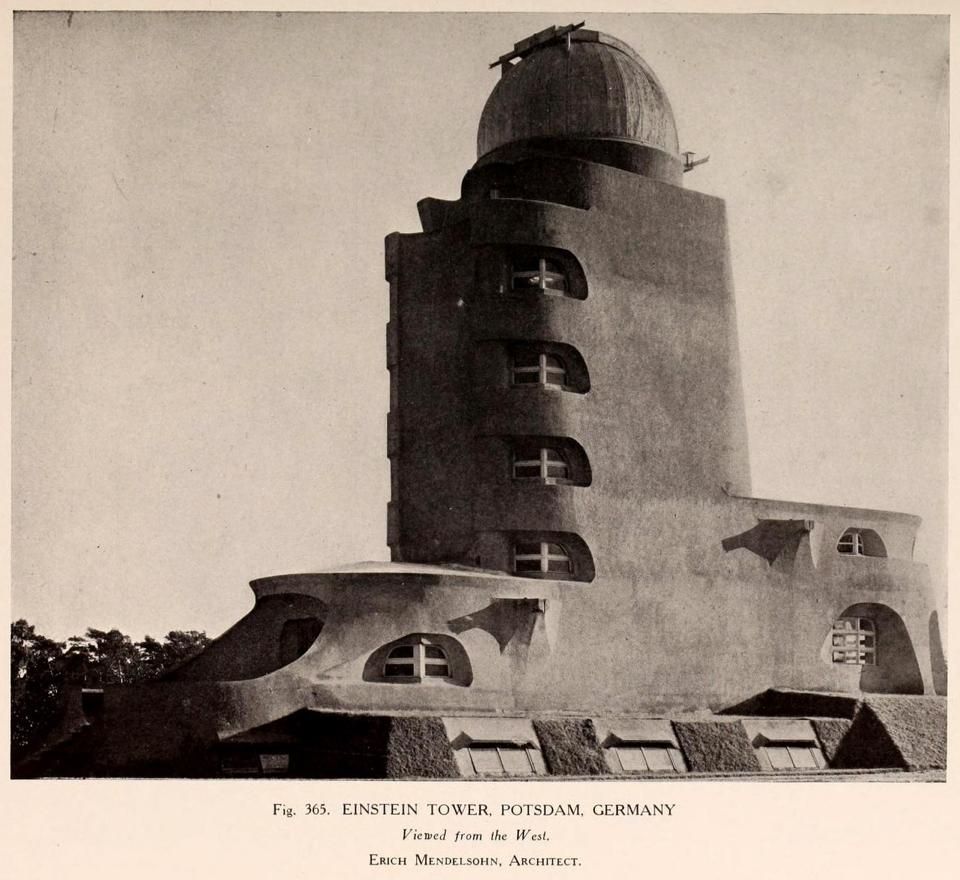

As such endeavors suggest, Expressionism was a romantic movement. It can rightfully be criticized for not having been able to resist the seduction from formal aspects of architecture at the expense of all other concerns. Many Expressionist designs look like they are ready to depart. This notion of mobile architecture was aimed to symbolize metamorphosis and transcendence. Taut’s early apartment buildings of the 1910s exemplify these goals. In these large structures, he attempted to engender a communal impression through color and facade articulation. Similarly, Erich Mendelsohn’s early sketches express a dynamic feeling. These designs show forms that are derived from structure and the expression of the purpose of the building. They are rather abstract renderings of these intentions. The essence of the projects is artistic, not architectural, as they are not primarily meant to be realized. Mendelsohn wanted to formulate a new style based on industrial forms and materials. The gesture of drawing coincides with aerodynamic lines, producing a formal expression of “industrial” energy. Following the contour of a form with one’s eyes is the only thing needed to understand the design. In his Einstein Tower (1924) in Potsdam, Germany he attempted to represent energy through mass. The form of the tower wants to show the movement that is immanent in the building mass. Thus, there is a melding of technical function and monumentality. The building implies the potential to leap forward, as if it contained energy.

Concerns with materials and meaning produced other variations. Fritz Höger’s Chile House (1923) in Hamburg, for example, was a speculative office building in the tradition of the Hamburg Kontorhaus (commercial office building). The structure is a frame built entirely of brick. Thus, it became a counterpart to the other Expressionist material: glass. Brick alluded to a craft tradition and was better suited to Hamburg’s damp climate. The bricks were vitrified. In its form, the Chile House evokes the image of a ship. Its sharp corners parallel the crystalline forms of other Expressionist architects. In general, the form alludes to many images, such as a fish or a flag.

A group of younger architects formed the Crystal Chain under Taut’s leadership. This was mostly a group of solitary criers in the wilderness of the industrial world who formed a magic circle of mystery among themselves. Most of the members shared the wish for large-scale buildings that would bring all the arts together. The letters they wrote to one another document their attempts to go back to the roots, the origins, of creative architectural activity. Among the most charismatic members was Hermann Finsterlin, who had studied natural sciences and considered himself to be the Darwin of architecture. His conception of architecture was almost biological, dealing primarily with form and showing an evolution that dealt with biological urges and species, not with style. Similarly, he considered his visionary designs to be natural living organisms assembled from basic shapes. His sketches show strong anthropomorphic similarities.

In Dutch Expressionism, designing was seen primarily as an individual struggle of the architect’s vision against materials and the construction reality. Unlike the ideological emphasis of German Expressionism, the Dutch School’s buildings are characterized by a tendency toward composition and construction. Their architecture is distinguished by an emphasis on the plastic force of the building form. Buildings were designed and constructed according to the principles of organic growth found in nature. This was an architecture that looked like sculpture, in which materials were molded to enclose space. The architects used hand-formed bricks and tiles in various colors and shaped chimneys, balconies, towers, and ornamentation as sculptural additions to the building form. In this manner, purely functional parts were transfigured into symbolic aspects expressing the joy of everyday life. This merger between architecture and sculpture successfully expressed the inner aspirations of the architect and his clients. Building outlines are simple and firm and articulated in sinuous rhythms. This allowed architects to display emotion in their designs by endowing the building materials with their spirit and gave their buildings a unique character that allowed the inhabitants to identify with their homes. Architecture as art could be created only through an inward struggle. Through all of this, the architects expressed the essential character of society as a communal whole. In their buildings, architects tried to anticipate a better future, which also reflected a nostalgic longing for the social fabric symbolized in medieval architecture.

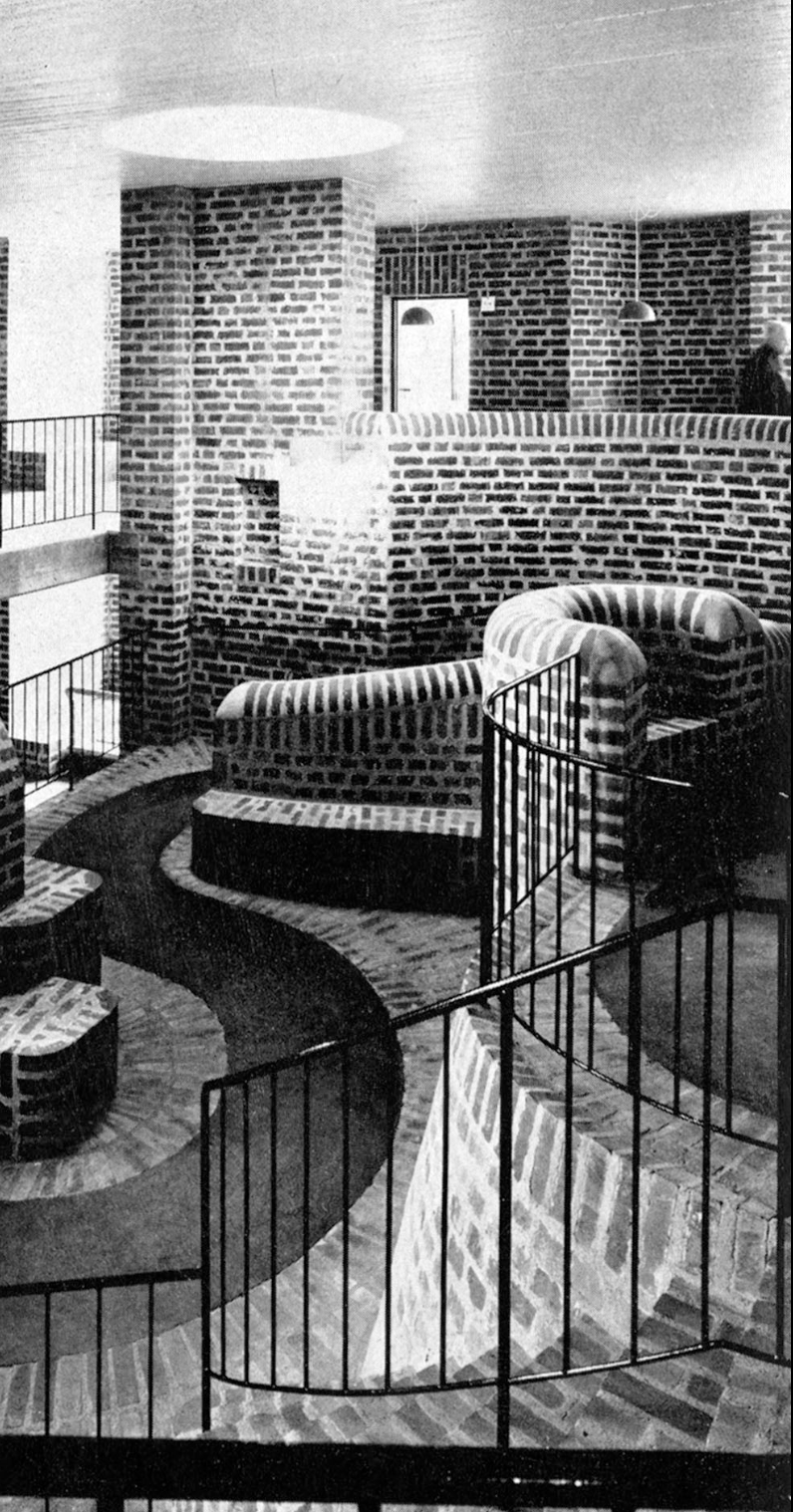

Consequently, most Dutch Expressionist work is found in the area of communal, lowincome workers’ housing. Michel de Klerk and Piet Kramer attempted to renew the existing Dutch communal housing traditions rather than inventing something completely novel. They generally used traditional materials and construction systems rather than the new industrial materials and structures. De Klerk’s buildings excel at making conventional forms more piquant, primarily by presenting truncated shapes. He linked the individual elements and units of his forms in a dynamic manner. Masses rise and fall rhythmically, and large wall expanses are broken by terraces. His Eigen Haard Housing Estate (1913–21) in Amsterdam is a masterpiece in sculptural modeling. De Klerk wanted to make people happy through forms. Here, he created a fantastic environment. The overall forms follow closely the requirements of urban architecture—namely, those of articulating the traffic flow of the street—whereas individual details and facade articulations are Expressionist. There are many references to the sea and the nautical world in the forms and facades. Tile work and polychromatic brickwork are used to provide these impressions. Cylindrical forms further emphasize the corners of the buildings and are used to articulate communal entrances. Tower forms are also meant to express the village nature of this estate. The entire building complex and its details allude hypothetically to remnants from past, medieval cultures.

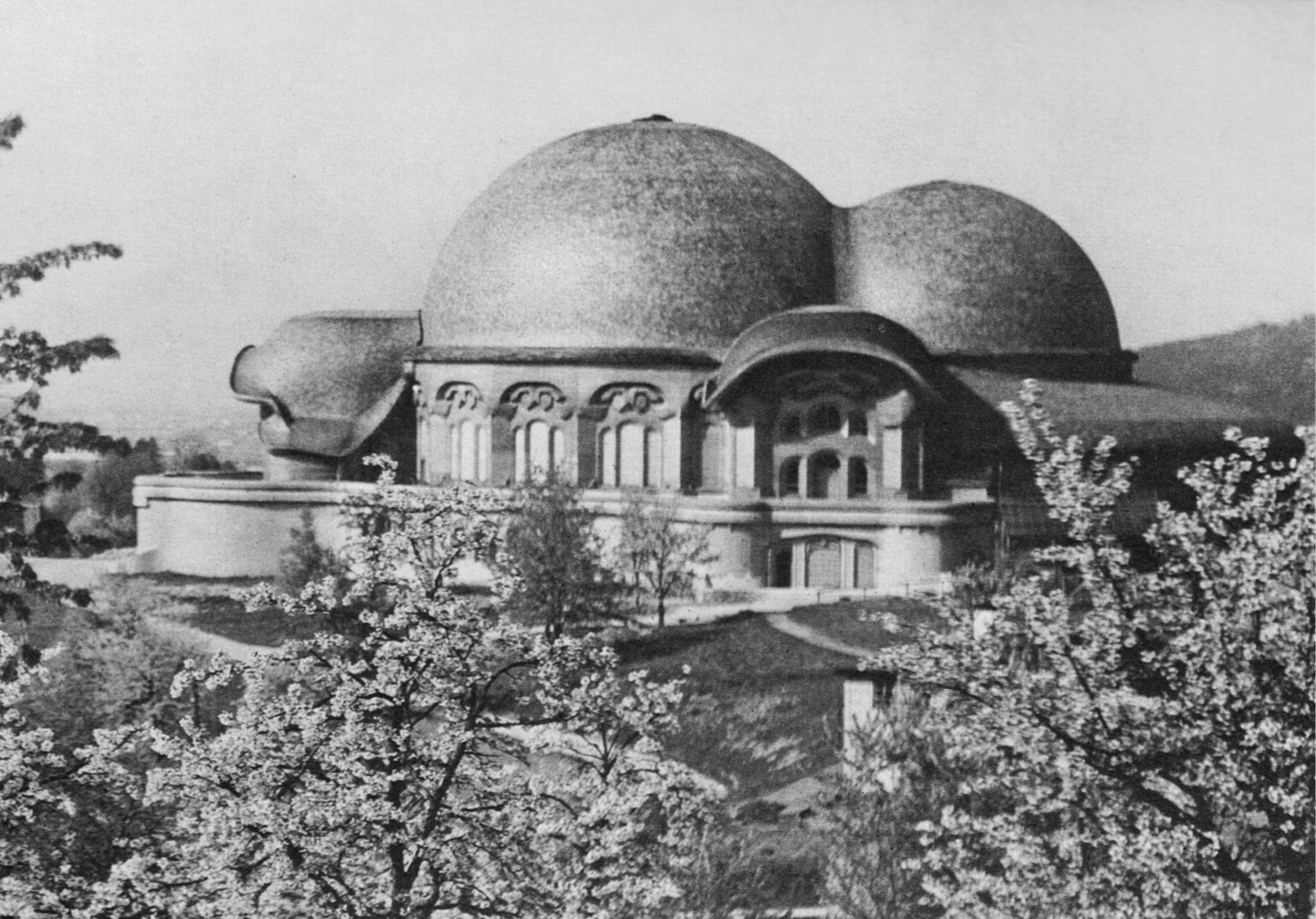

Rudolf Steiner represents the theosophical wing of Expressionism. His work may also serve as an example for the innovative use of new materials of this movement. In his Goetheanum (1927) in Dornach, he exploited reinforced concrete to achieve an imaginative shape. This produced a unique design that has no sources or progeny. Its form and details repeat a basic motif that Steiner had determined at the outset of the design. Nothing in the building exists in isolation: every part and detail strives toward the next one. Steiner’s purpose was simply to find the way to the spirit through architecture. In this, he also showcases the mood of ideological and religious awakening of Expressionism. He was above all interested in alluding to the spiritual states that loom behind physical reality. For him, architecture was the medium that stimulates forms of thought that lead to spiritual rejuvenation.

With the German economic recovery of 1923, Expressionism ceded to a more sober, pragmatic approach to architecture. Constructing cheaply and abundantly became more pressing needs than spiritual rejuvenation. In Amsterdam, for example, architects were forced to use prefabricated building elements to reduce construction costs. A craftoriented look was replaced by industrial forms, and individualistic designs lost out against the representation of a sober objectivity. Ultimately, the International Style mainstream prevailed. Expressionist architecture was given a bad reputation as the scapegoat for the adverse political reality in Germany after 1933. Siegfried Giedion denigrated its designs as “Faustian outbursts against an inimical world,” “fairy castles to stand on the peak of Monte Rosa,” or “concrete towers as flaccid as jellyfish.” The early chroniclers of the International Style accused it of having reversed the push for a new architecture that the signs of the year 1914 announced. These evaluations continued the denunciation of Expressionism at the 1937 “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich, organized by the National Socialists. It was this event that prompted Marxist critics to proclaim that the same forces that had led to Expressionism also had led to Fascism. Expressionism was not even accepted as a style; it was accorded value only as the manifestation of the revolutionary fervor that existed in Germany after World War I. Although the movement was credited with tearing down the cultural heritage of the 19th century, it was accepted only as a synonym for opposition and lost out against the International Style. The view of Expressionism as simply a revolt has in the meantime ceded to one that appreciates it as a style favoring personal creative liberty over the scientific rationality of the International Style. Beginning in the 1950s with the Englishman Reyner Banham, architectural critics began to reevaluate functionalism. Ultimately, this development resulted in the postmodern dismissal of the International Style. It was also felt that Expressionism could not satisfactorily be dealt with from only a purely formal, stylistic perspective. Expressionism is instead seen as a broad cultural phenomenon that encompassed a variety of artistic methods. Concurrent with this scholarly reevaluation came a resurgence of typically Expressionist forms in architecture. Acclaimed modernists, such as Le Corbusier and Alvar Aalto, created designs in which human activity and existence were seen as the central architectural metaphors. Architects such as Eero Saarinen and Jørn Utzon spearheaded the neo-Expressionist movement. The material innovations that were produced in the American war industry finally allowed architects to build expressive formal fantasies. Eero Saarinen’s TWA Terminal (1962) at Kennedy Airport in New York and Utzon’s Opera House (1973) in Sydney testify to this situation. Original Expressionists, such as Hans Scharoun and Mendelsohn, realized their earlier visions in such designs as the Philharmonic Hall (1963) in Berlin and Park Synagogue (1953) in Cleveland. Another significant part of neo-Expressionism is centered around the Waldorf Schools, which had been founded by Rudolf Steiner and which continue to imbue its school buildings, especially in England, with values identical to those that informed Steiner’s Goetheanum.

HANS MORGENTHALER

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2004. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

Drawings |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1910-1911, Bismarck Tower, Hans Scharoun |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1915, House of Worship, Museum, Hermann Finsterlin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1915, Becker Residence, Chemnitz, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1915, Becker Residence, Chemnitz, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1915, Architectural Study, Michel de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917, Small Country House in the Dunes, Adolf Eibink and J. A. Snellebrand |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917, Small Dancing School, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1918, Snow Glacier Glass, Bruno Taut |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1918, The Crystal Mountain, Bruno Taut |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1918, Film Studio, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1918, Warehouse, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1918, Untitled, Johannes Molzahn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1919, Untitled, Hans Scharoun |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1919, Untitled, Max Taut |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1919, Monument to Labour, Wassili Luckhardt |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1919, Temple, Paul Goesch |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1920, Fantasy in Form, Hans Luckhardt |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1920, Bridge on the Leidseplein, Amsterdam, Hendrikus Theodorus Wijdeveld |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1920, Dream in Glass, Hermann Finsterlin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1920, Gloria, Rudolf Schwarz |

| |

|

| |

. Colour sketch for the Main Hall, Hoechst Pigment and Dye Corporation. C. 1920..png) |

| |

c. 1920, Colour sketch for the Main Hall, Hoechst Pigment and Dye Corporation, Peter Behrens |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1920, Fortress, Hermann Finsterlin |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921, High-rise Building at Friedrichstrasse Station, Berlin, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921, Residence and Studio, Wenzel August Hablik |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921, Blossom House, Max Taut |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921, High-rise Building at Friedrichstrasse Station, Berlin, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe |

| |

|

| |

. Kallenbach Residence, Berlin. 1921..png) |

| |

1921, Kallenbach Residence, Berlin, Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer |

| |

|

| |

. Kallenbach Residence, Berlin. 1921. 1.png) |

| |

1921, Kallenbach Residence, Berlin, Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921-1922, Bridge City, Uriel Birnbaum |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921-1922, Kaleidoscope City, Uriel Birnbaum |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1922, High-rise Building on Kemperplatz, Berlin, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1922, Cinema II, Hans Scharoun |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1922, House of the People, Max Taut |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1922, De Hoop Boat Club, Amsterdam, Michel de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Tower in a Garden City, Haifa, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

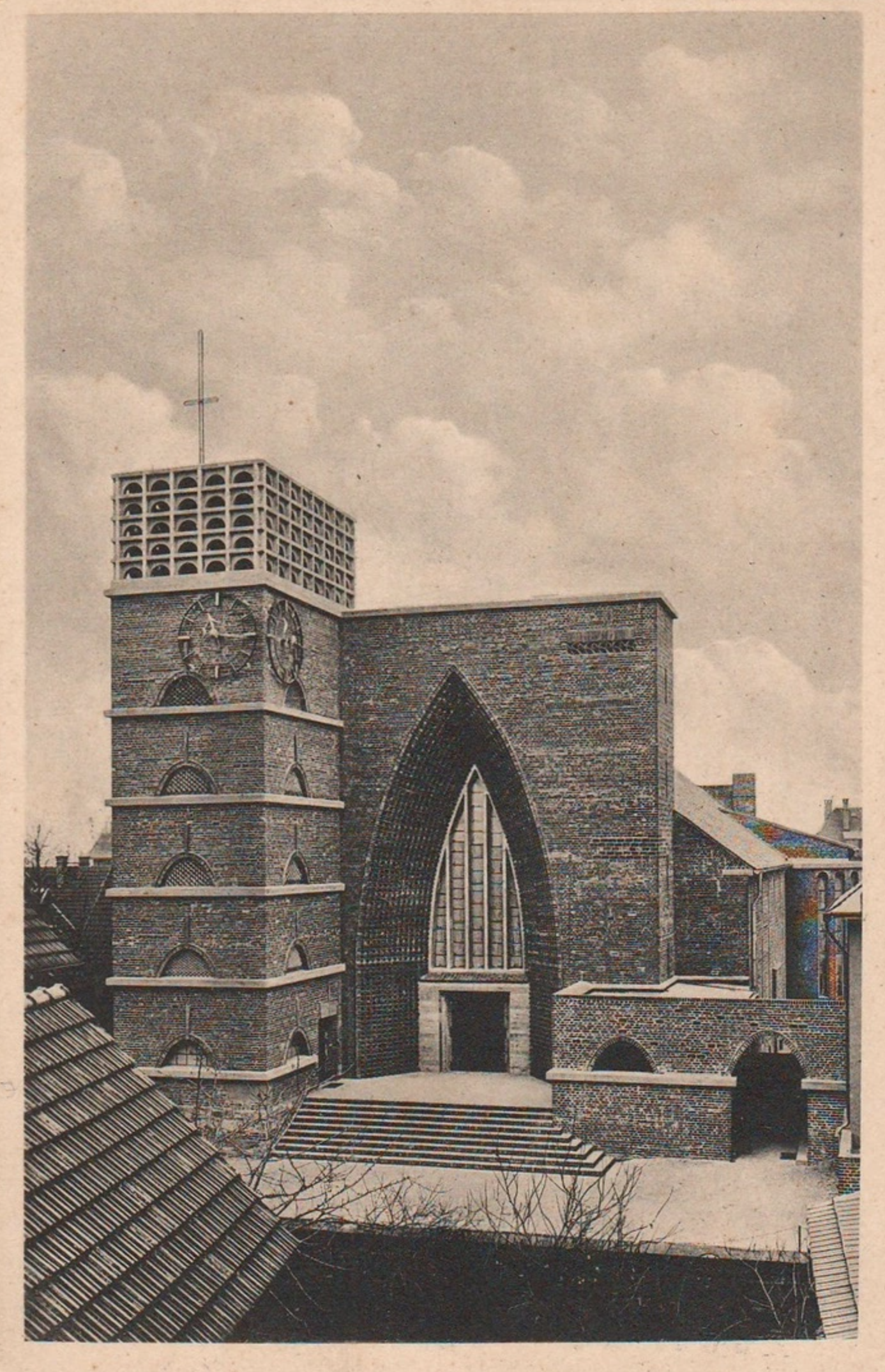

c. 1923, Soldiers' Memorial Church, Göttingen, Dominikus Böhm |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Auction Hall for Flower Sales, Aalsmeer, Michel de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Church, Constance, Otto Bartning |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

c. 1924, Central Building in a Large City, Paul Thiersch |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925, Metropolis, Second Version. Dawn, Erich Kettelhut |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925, Metropolis, Second Version. The New Tower of Babel, Erich Kettelhut |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925, Heineken's Brewery, Rotterdam, First design, Willem Kromhout |

| |

|

| |

. Lenin Mausoleum, Moscow. 1926..png) |

| |

1926, Lenin Mausoleum, Moscow, Hendrik Petrus Berlage (in cooperation with E. E. Strasser and B. Wille) |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Date unknown, Untitled, Hans Poelzig |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

Buildings |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

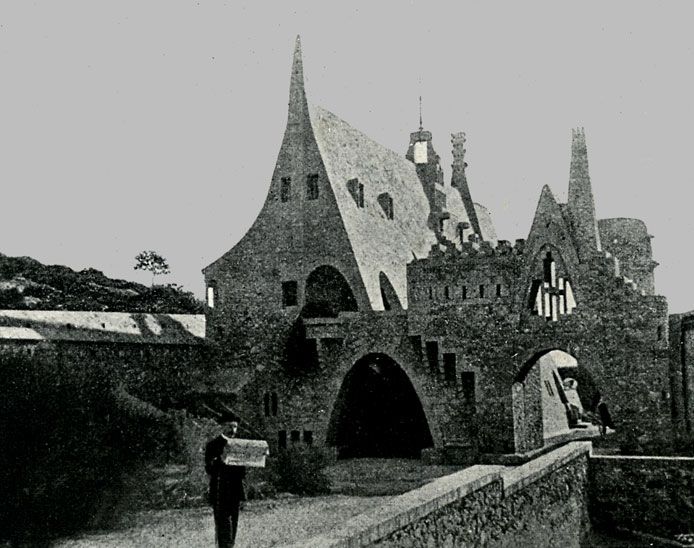

1888-1895, Bodegas Güell, Garraf, SPAIN, Francesc Berenguer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

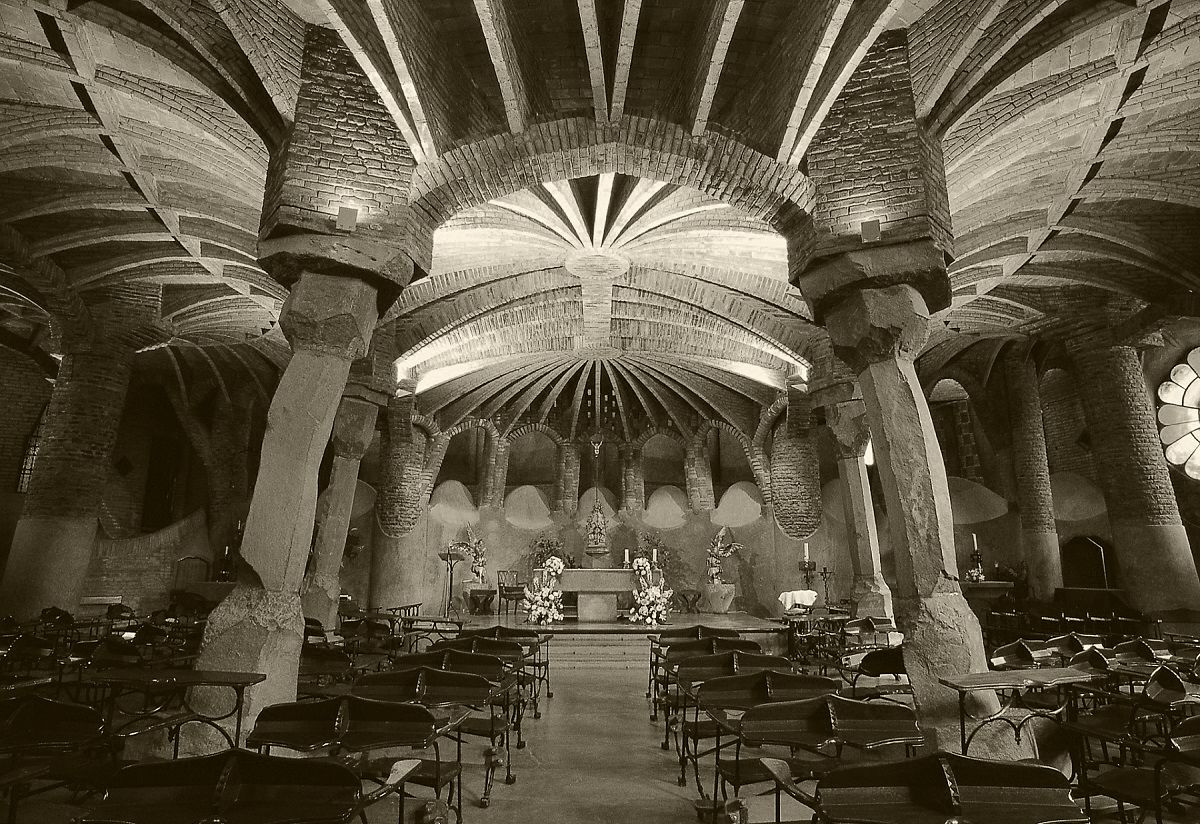

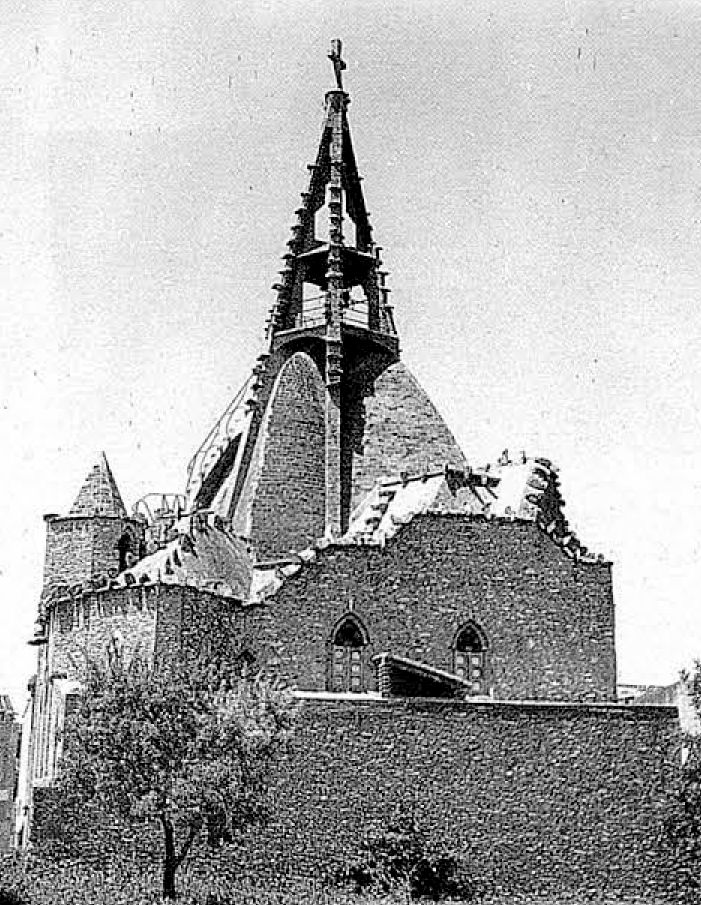

1898-1914, Chapel of the Colonia Güell, Crypt of Santa Coloma de Cervelló, SPAIN

Antoni Gaudi |

| |

|

| |

, POLAND, Hans Poelzig.jpeg) |

| |

1911, Water tower, Posen (Poznań), POLAND, Hans Poelzig |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1911-1916, Scheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Johan Melchior van der Meij |

| |

|

| |

, Dornach, SWITZERLAND, Rudolf Steiner.jpeg) |

| |

1913-1914, Studio building (Glass House), Dornach, SWITZERLAND, Rudolf Steiner |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1913-1915, Eigen Haard, Spaarndammerplantsoen, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1913-1920, First Goetheanum, Dornach, SWITZERLAND, Rudolf Steiner |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1914, Torre dels Ous, Sant Joan Despí, SPAIN, Josep Maria Jujol |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1914, Glass Pavilion at the Werkbund exhibition, Cologne, GERMANY, Bruno Taut |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1914-1915, Boilerhouse, Dornach, SWITZERLAND, Rudolf Steiner with Alfred Hilliger |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917, Park Meerwijk, Bergen, NETHERLANDS, J.F. Staal |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917-1920, Hembrugstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1918-1919, Meezennest and Meerlhuis houses, Bergen, GERMANY, Margaret Kropholler |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1920-1922, Radio station, Ootmarsum, NETHERLANDS, Julius Maria Luthmann |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921-1923, Conversion of Rudolf-Mosse-Haus, Jerusalemer Strasse, Berlin, GERMANY, Erich Mendelsohn with Richard Neutra and R. P. Henning |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

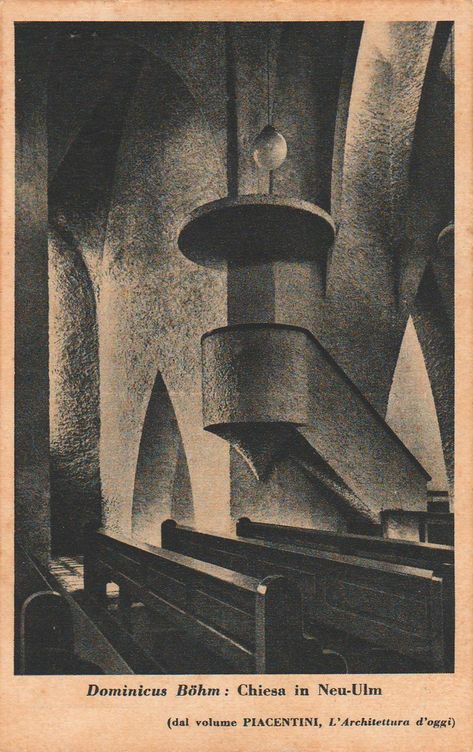

1921-1926, St Johannes Baptist, Neu-Ulm, GERMANY, Dominikus Böhm |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921-1940, Grundtvigs church, Copenhagen, DENMARK, Peter Vilhelm Jensen-Klint, completed by Kaare Klint |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Chile House, Hamburg, GERMANY, Fritz Höger |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Chapel of the Sacrament, Vistabella, SPAIN, Josep Maria Jujol |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1924, Einstein Tower, Potsdam, GERMANY, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1924-1926, Montanhof, Hamburg, GERMANY, Hermann Distel and August Grubitz |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

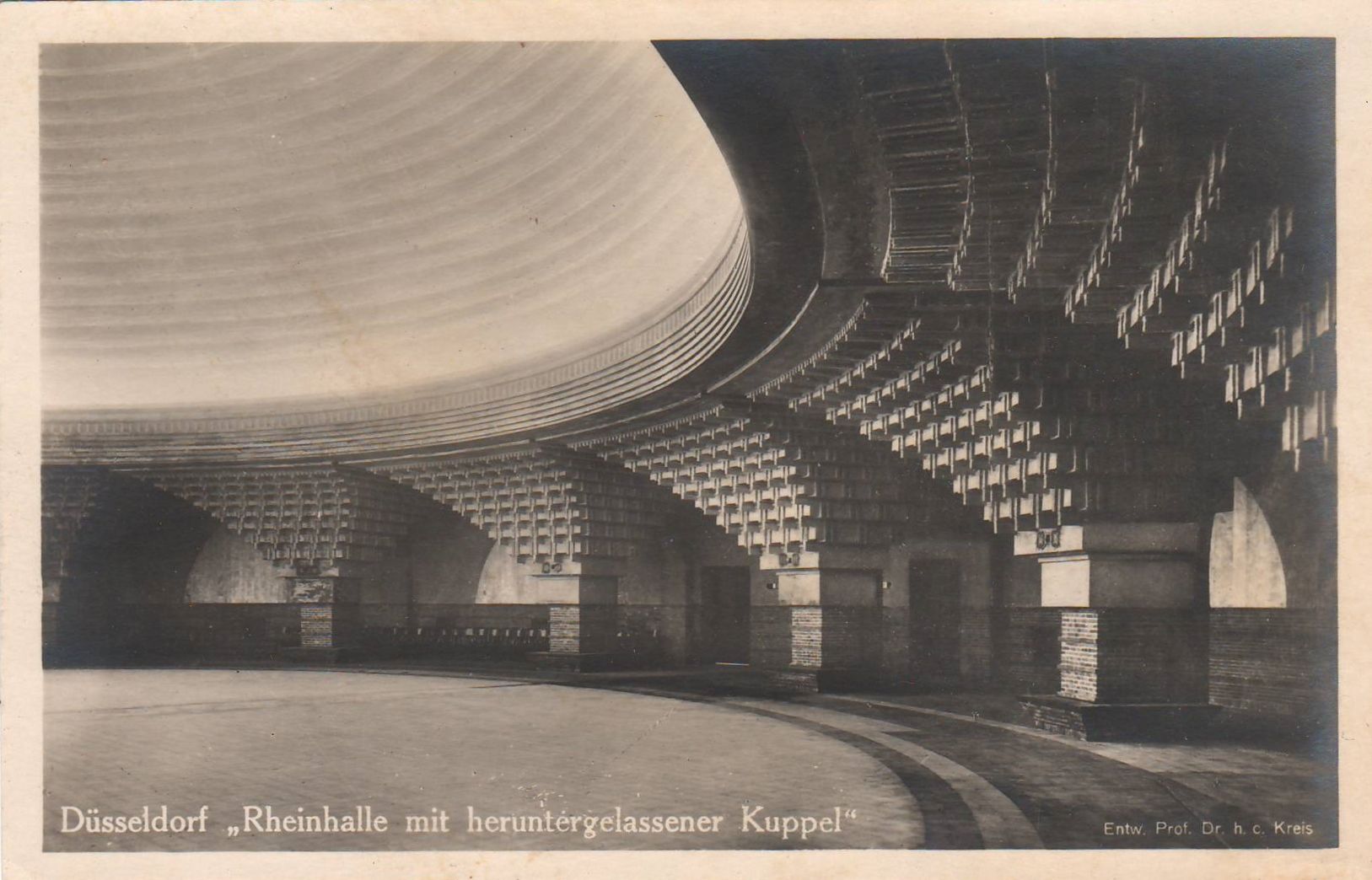

1925-1926, Rheinhalle, Düsseldorf, GERMANY, Wilhelm Kreis |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1926, Christkönigskirche, Mainz-Bischofsheim, GERMANY, Dominikus Böhm |

| |

|

| |

, Limburg an der Lahn, GERMANY, J. Hubert Pinand.jpeg) |

| |

1927, St Marien (Pallotinerkirche), Limburg an der Lahn, GERMANY, J. Hubert Pinand |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928, Kaufhaus Schocken, Stuttgart, GERMANY, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1930, St. Engelbert, Cologne-Riehl, GERMANY, Dominikus Böhm |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1964, Habitacle no. 2, Meudon, FRANCE, André Bloc |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1966-1968, Old people's home, Düsseldorf-Garath, GERMANY, Gottfried Böhm |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1968-1974, Church of the Holy Family,

Salerno, Italy, PAOLO PORTOGHESI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

DE KLERK, MICHEL

GAUDÍ, ANTONI

MENDELSOHN, ERICH

POELZIG, HANS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1913-1921, Eigen Haard Housing Estate, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Michel de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

1923, Chile House, Hamburg, GERMANY, Fritz Höger |

| |

|

| |

1924, Einstein Tower, Potsdam, GERMANY, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

1928, Kaufhaus Schocken, Stuttgart, GERMANY, Erich Mendelsohn |

| |

|

| |

1968-1974, Church of the Holy Family,

Salerno, Italy, PAOLO PORTOGHESI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

AMSTERDAM SCHOOL; ART NOUVEAU; ARTS AND CRAFTS; GLASS; INTERNATIONAL STYLE

FURTHER READING

Benson, Timothy O., editor, Expressionist Utopias: Paradise, Metropolis, Architectural Fantasy, Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1993

Borsi, Franco, and Giovanni Klaus Koenig, Architettura dell’Espressionismo, Genoa: Vitali e Ghianda, and Paris: Fréal, 1967 (contains summaries in French, German, and English)

Casciato, Maristella, editor, La Scuola di Amsterdam, Bologna: Zanichelli, 1987; as The Amsterdam School, Rotterdam: 010 Publishers, 1996

Conrads, Ulrich, and Hans G.Sperlich, Phantastische Architektur, Teufen, Switzerland: Niggli, 1960; as The Architecture of Fantasy: Utopian Building and Planning in Modern Times, translated, edited, and expanded by Christiane Craseman Collins and George R.Collins, New York: Praeger, 1960; as Fantastic Architecture, London: Architectural Press, 1963

Franciscono, Marcel, Walter Gropius and the Creation of the Bauhaus in Weimar : The Ideals and Artistic Theo ries of Its Founding Years, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971

Pehnt, Wolfgang, Expressionist Architecture, London: Thames and Hudson and New York: Praeger, 1973

Pehnt, Wolfgang, Architekturzeichnungen des Expressionismus, Stuttgart, Germany: Hatje, 1985; as Expressionist Architecture in Drawings, translated by John Gabriel, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, and London: Thames and Hudson, 1985

Sharp, Dennis, Modern Architecture and Expressionism, New York: Braziller, and London: Longmans, 1966

Whyte, Iain Boyd, The Crystal Chain Letters: Architectural Fantasies by Bruno Taut and His Circle, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1985 |

| |

|

|