| ALL |

|

AMSTERDAM SCHOOL

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

The Amsterdam School was comprised of Dutch architects active between 1910 and 1930 whose work was associated with Expressionism and promulgated by the publication Wendingen. During World War I and for a decade thereafter, the striking and controversial work of the Amsterdam School transformed entire portions of its eponymous city and influenced architecture throughout the Netherlands. Although almost every building type was addressed, the major monuments are government funded ensembles of workers’ dwellings arranged in perimeter blocks that brought a new scale to Dutch cities. Paradoxically, although its members sought unique solutions for each commission, a readily identifiable group style emerged, and collaborations were frequent. Characterized by a luxurious fantasy and individualistic details, the work came under fire in the later 1920s from proponents of the functionalist Nieuwe Bouwen; subsequently, the Amsterdam School was written out of the literature. But in the 1970s, reevaluation commenced; many of the buildings have been restored and once again are a magnet for architects and urbanists.

The cradle of the Amsterdam School was the atelier of Eduard Cuypers (1859–1927). Working there at various times during the first decade were its future leader, Michel de Klerk (1884–1923) and such important representatives as Johann Melchior van der Mey (1878–1949) and Pieter Lodewjik Kramer (1881–1961). Other future acolytes in that office who absorbed Cuypers’s credo that architecture was first and foremost an art that must transcend, while serving the pragmatic realities of program and resources, included G.F.LaCroix (1877–1923), Nicolaas Landsdorp (1885–1968), B.T.Boeyinga (1886– 1969), Jan Boterenbrood (1886–1932), J.M.Luthmann (1890–1973), and Dick Greiner (1891–1964). Encyclopedia of 20th-century architecture 88 Cuyper’s peculiar synthesis of Austrian and German Jugendstil (Art Nouveau), British Arts and Crafts, Belgian Art Nouveau, 17th-century Dutch architecture, and Indonesian art appears in more abstract guise in all of their work. Better known architects of Cuypers’s generation such as Willem Kromhout (1864–1940) and K.P.C.de Bazel (1869– 1923) also were admired exemplars but with the doyen of Dutch architecture, H.P.Berlage (1856–1934), they had a more complicated relationship. In his one published statement of 1916, de Klerk criticized Berlage’s work for its excessive sobriety and lack of representational character in both materials and function. Yet they followed his use of geometric systems to proportion plans and elevations, and in the late teens and early 1920s, Berlage worked with members of the Amsterdam School and responded to their delight in piquant invention; his housing around the Mercatorplein (1925–27) indicates a mutual regard.

Although the Amsterdam School, unlike its rival, De Stijl, embraced no specific theoretical program, its members were united not only by stylistic practice and the conviction that architecture was first and foremost an inclusive art that should be aesthetically accessible to people of all classes, but also by training (many were autodidacts or studied in courses outside the main professional school at Delft). To understand the movement’s rapid and widespread—if short-lived—influence, it is necessary to review several peculiarly Dutch institutions through which its “members” exercised power. The club Architectura et Amicitia (A et A), founded in 1855, during the teens and twenties was led by those sympathetic to the artistic ideals of the Amsterdam School, whose work was privileged in its publications, especially Wendingen (literally, “Turnings,” but in the sense of departures or deviations), which under the partisan edi-torship of Hendricus Theodorus Wijdeveld (1885–1987) appeared monthly from 1918 to 1928. The club also held competitions and exhibitions that disseminated designs conforming to the group’s aesthetic position; it was in a review of the display mounted by A et A in 1916 that the name Amsterdamse School first appeared in print. Amsterdam’s municipal organizations also played a role. The Department of Public Works was staffed by its adherents, as testified by the street furniture, bridges, public baths, schools, and offices for city agencies that were designed and executed between 1917 and 1930. The Social Democrats responsible for housing policy in Amsterdam were admirers, for they believed that the work of the Amsterdam School dignified the neighborhoods of the working- and lower-middle-class families for whom they were responsible. The Commission of Aesthetic Advice (Schoonhei dscommissie), which passed judgment on exterior design, also was dominated by its advocates, much to the chagrin of architects of other stylistic persuasions, who often had to change their designs to conform to Amsterdam School conceptions.

Multicolored brick and tile, quintessentially Dutch materials, were employed for structure and cladding but used in unprecedented ways, in combination with concrete, stone, and powerful new mortars, to create unique configurations that pulsate with vitality. The dynamism of the modern metropolis inspired many of the formal strategies employed by the Amsterdam School, yet vernacular, historical, and even naturalistic references, as well as motifs from German and Scandinavian architecture and Frank Lloyd Wright, leavened the imagery. This was a narrative architecture that used massing and ornament iconographically, to contextualize each commission. Accusations of irrationalism and facadism were exaggerated; when commissions allowed, interior spaces Entries A–F 89 were as ingenious as exterior envelopes and in each case expressed the realities of the program. After 1925 socioeconomic events curtailed the extravagant conceits of the Amsterdam School and led to a more repetitious and less imaginative vocabulary, but during its reign in the Netherlands it was responsible for such remarkable buildings as the Scheepvaarthuis, 1912–16 (by Van der Meij, Kramer, and de Klerk), and the housing estates Eigen Haard, 1914–18 (de Klerk) and De Dageraad, 1919–21 (de Klerk and Kramer), all in Amsterdam, plus the villas compromising Park Meerwijk, 1917, in Bergen (Kramer, La Croix, plus J.F Staal and Margaret StaalKropholler , the Netherlands’ first female architect), the Bijenkorf Department Store in The Hague, 1925–26, by Kramer, and the post office in Utrecht 1917–24, by Joseph Crouwel.

HELEN SEARING

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2004. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1912-1916, the Scheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, Michel de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1913-1915, Eigen Haard, Spaarndammerplantsoen, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917, Park Meerwijk, Bergen, NETHERLANDS, J.F. Staal |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

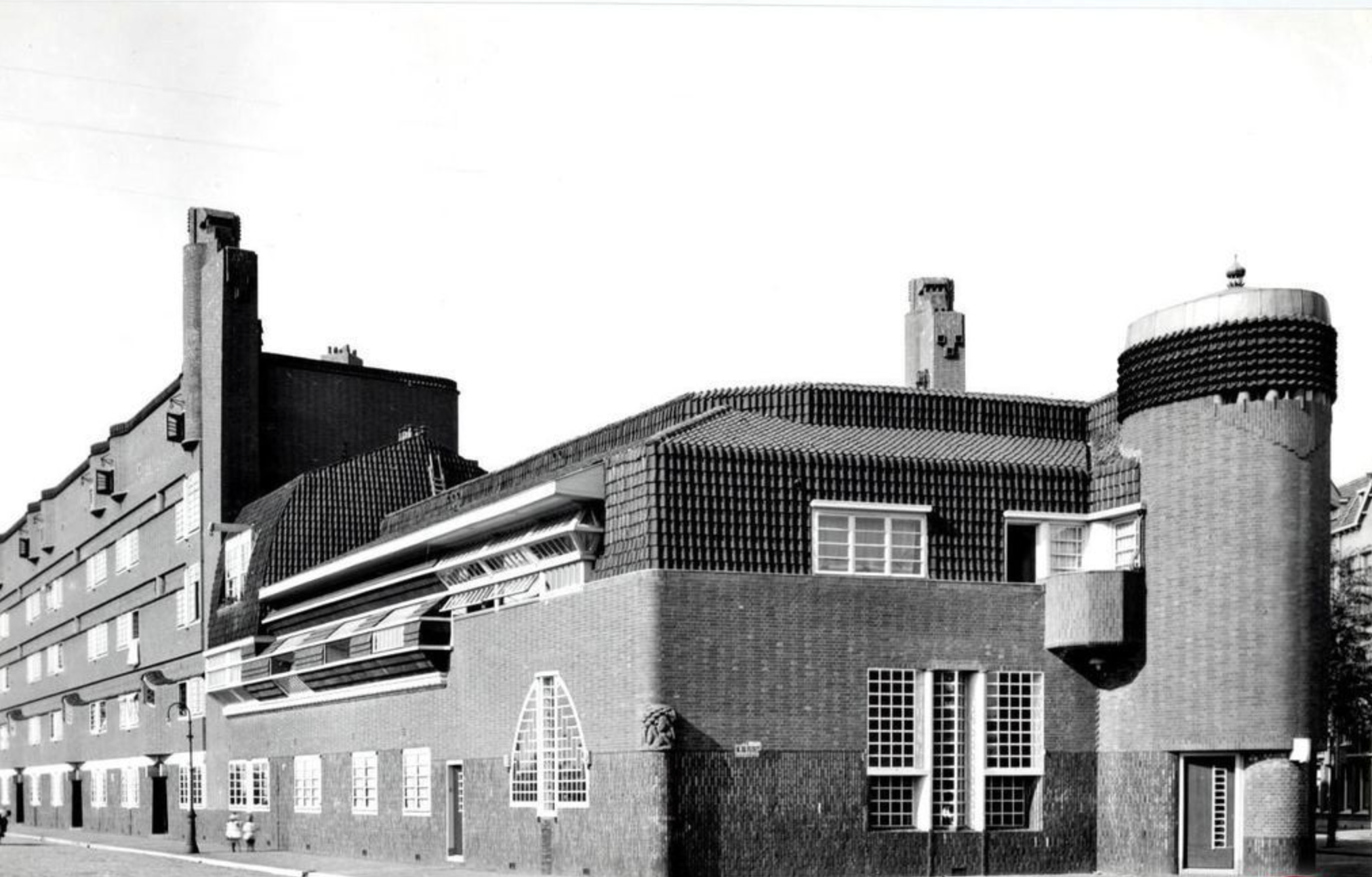

1917-1920, Postkantoor, Zaanstraat/Oostzaanstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917-1920, Hembrugstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1920, Insulindeweg/Celebesstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, H.Th. Wijdeveld |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921-1922, Dageraad, P .L. Takstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, P.L. Kramei |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1921-1923, Henriëtte Ronnerplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, M. de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1922-1924, Smaragdstraat, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS,

J.C. van Epen |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1922-1927, Huize Lydia, Roelof Hartplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, J. Boterenbrood |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925–1926, the Bijenkorf Department Store, The Hague, NETHERLANDS, Piet Kramer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

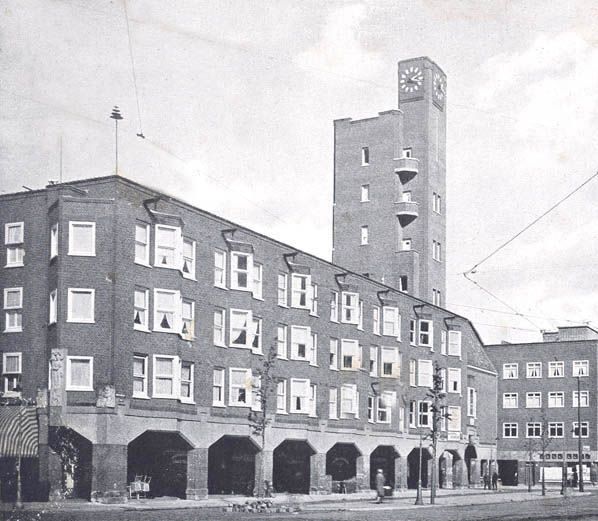

1925-1927, Mercatorplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, P. Berlage

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1926-1928, St. Gerards Majella, Ambonplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS,

J. Stuyt

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1928, Synagoge, Jacob Obrechtplein, Amsterdam, NETHERLANDS, H. Elte

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

BERLAGE, HENDRIK PETRUS

DE KLERK, MICHEL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1912-1916, the Scheepvaarthuis, Amsterdam, Michel de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

1914-1918, the housing estates Eigen Haard, Amsterdam, Michel de Klerk |

| |

|

| |

1917, Park Meerwijk , Bergen, J.F. Staal |

| |

|

| |

1925–1926, the Bijenkorf Department Store, The Hague, Piet Kramer |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

AMSTERDAM; DE STIJL; EXPRESSIONISM; NETHERLANDS;

FURTHER READING

Baeten, Jean Paul, Deonbekende Amsterdamse School—The Unknown Amsterdam School, Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 1994

Bock, Manfred (editor), Michel de Klerk: Architect and Artist of the Amsterdam School, Rotterdam: NAi, 1977

Casciato, Maristella, The Amsterdam School, Rotterdam: 010, 1996

Fanelli, Giovanni, and Ezio Godoli, Wendingen 1918–1931: Documenti del l’arte o landese del Novecento, Florence: Centre Di, 1982

Frank, Suzanne S., Michel de Klerk (1884–1923) : An Architect of the Amsterdam School, Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1984

Mattig, Eric, and Jan Derwig, Amsterdam School, Amsterdam: Architectura et Natura, 1991

Mieras, J.P., and Francis Yerbury, Dutch Architecture of the Twentieth Century, London: Ernest Benn, 1926

Pehnt, Wolfgang, Expressionist Architecture, London: Thames and Hudson and New York: Praeger, 1973

Trans J.Underwood and Edith Kuestner. Originally in German, Die Architektur des Expressionismus, Stuttgart: Gerd Hatje, 1973

Searing, Helen, “Amsterdam South: Social Democracy’s Elusive Housing Ideal,” VIA IV: Culture and the Social Vision, (1980)

Searing, Helen, “Architecture and the Public Works in Metropolitan Amsterdam,” Modulus, 17 (1984)

Wit, Wim de,Amsterdam School: Dutch Expressionist Architecture, 1915-30, MIT Press , 1983 |

| |

|

|