| ALL |

|

DE STIJL

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

De Stijl architecture offers dynamic conceptions of spatial relationships in reaction to conventionally static, grounded architecture from the beginning of the 20th century. Spatial innovation, based on principles developed by the De Stijl painter and writer Piet Mondrian from the philosophical-mathematical writings of M.H.Schoenmaekers, is clearly evident in three iconic De Stijl projects from the mid-1920s: Theo van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren’s Maison d’Artiste and Maison Particuliére and Gerrit Rietveld’s Schröder House in Utrecht, the Netherlands. These modernist touchstones represent the synthesis of ideal universal projections of space and everyday manipulations of life embedded within art. Architecture proved to be the ideal art form to represent De Stijl through its ability to transform space, surface, universal ideas, particular situations, exterior, and interior.

De Stijl as a collective modernist movement remains difficult to codify. Begun as a virtual assemblage of avant-garde artists based in the Netherlands, it was founded and controlled by the painter, writer, and architect Theo van Doesburg (1883–1931). To characterize De Stijl as a truly united group or school of artists and architects is to misrepresent the vicissitudes of a movement whose members were never in the same place at the same time.

Van Doesburg, the proselytizer for De Stijl, presented it to the world as a close-knit, avant-garde collaborative unit of like-minded individuals with common goals. The work of De Stijl was disseminated primarily through its periodical, De Stijl, published irregularly from 1917 to 1929 and in 1932 as a memorial issue for van Doesburg. Van Doesburg, as its editor, published art, architecture, graphic design, essays, and manifestos for an increasingly international audience.

De Stijl as a collection of diverse projects coalesced under van Doesburg in a desire to achieve international unity through “the sign of art. The clearest way to distill De Stijl is to examine its ideas made evident in painting, sculpture, graphic design, and, most significantly, architecture. Mondrian and van Doesburg strove to achieve an ideal unity through projecting the tension of opposites—a dialectical formation on its way to achieving synthesis through articulating and then annulling issues of the individual versus the universal, nature versus spirit, particular versus general. This was to be achieved through reform of past cultural conditions via Nieuwe Beelding, or new forming (Neoplasticism). Van Doesburg attempted radical change through De Stijl, derived from the international conflicts of World War I. He strove for universal synthesis rather than Dutch nationalism, as evidenced in “Manifesto 1 of ‘De Stijl,’ 1918,” published in Dutch, French, German, and English as “De Stijl,” “Le Styl,” “Der Stil,” and “The Style” De Stijl set out to negate the concept of style in a universal language through communicative art and architecture, and the concise format of the manifesto was its primary textual vehicle.

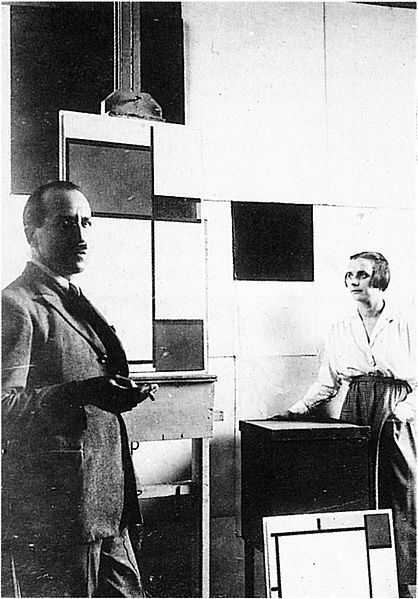

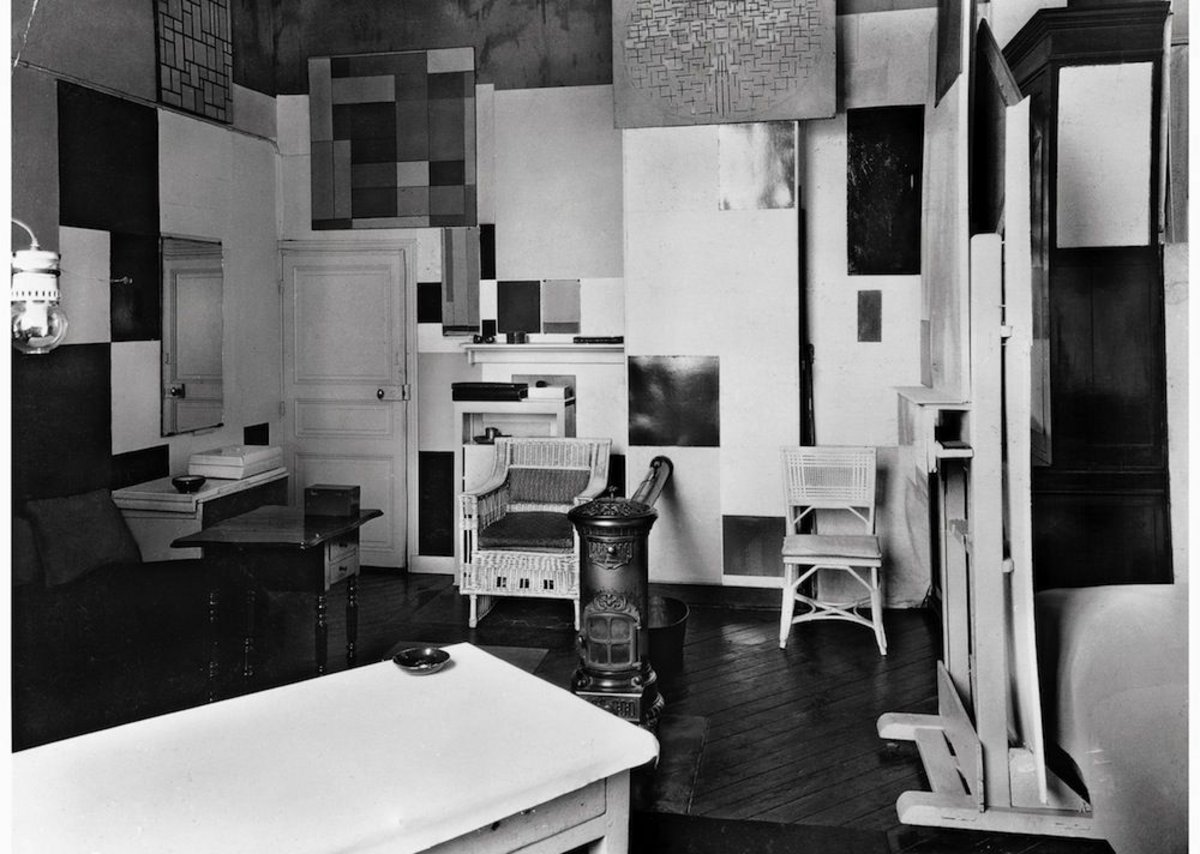

Van Doesburg contended that art (including architecture) embodies the spiritual force of life. He scrutinized the historical development of art as culminating “inevitably” in De Stijl as “The Style,” to synthesize all previous styles into a homogeneous purity. His ideological construct, looking simultaneously back into history and forward to a new art, codified polar opposites to create beauty in tension and synthesis. His manner of carrying out this process demanded collective work in all the arts, an ultimately unfulfilled desire. The painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) was De Stijl’s spiritual leader, providing its philosophical foundation (Neoplasticism) and language for representing pure relations of contrasts via horizontal-vertical oppositions and utilizing the primary colors red, blue, and yellow with the noncolors black, white, and gray. Beyond his neoplastic painting, Mondrian projected spatial architectural compositions and created rigorous interior designs for his own studio spaces in Paris and New York. Mondrian championed the development of De Stijl architecture, typically praising most built and unbuilt projects.

An early, perhaps the first, De Stijl work of architecture, appearing in its magazine in 1919, was the Villa Henny in Huis ter Heide, the Netherlands, by Robert van’t Hoff (1887–1979), designed in 1915. This often published reinforeed-concrete house was inspired by the residential architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright, whom van’t Hoff visited in the United States in 1914. The rectilinear, flat-roofed house features white planar surfaces with gray bands of trim, standing aloof from its natural setting. Interior rooms project symmetrically off a central space, a theme later transformed by van Doesburg.

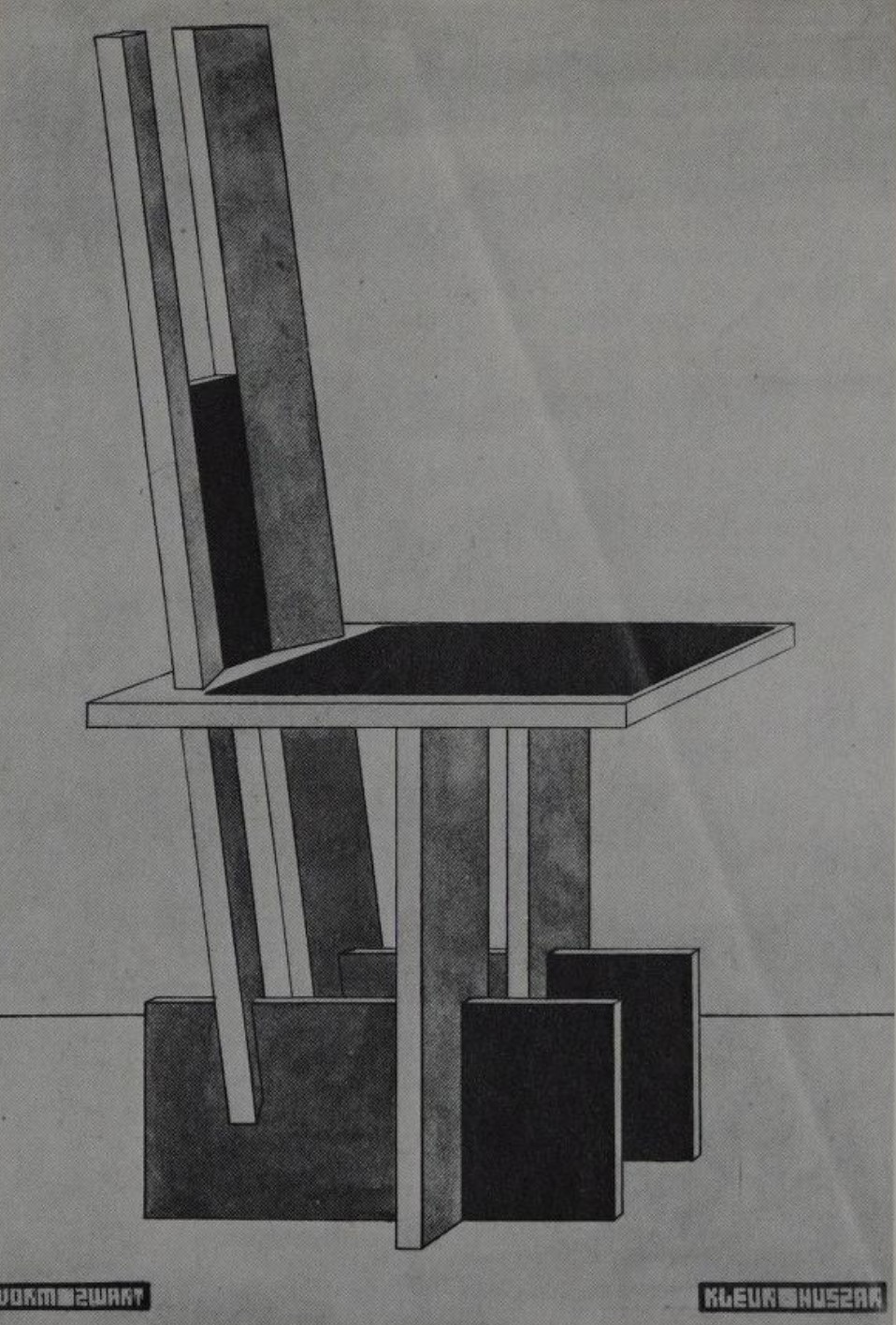

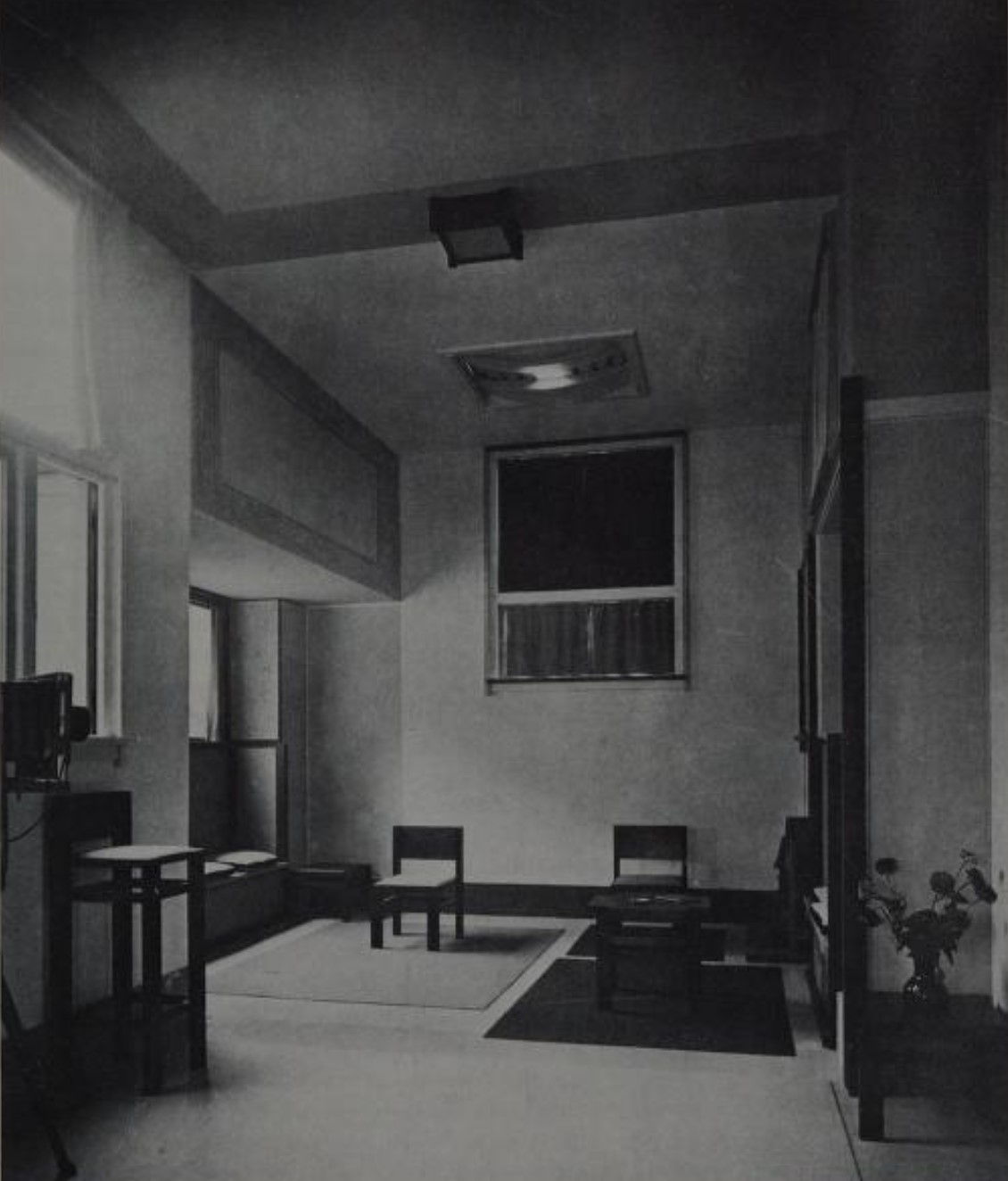

Other early De Stijl projects typically involved interior alterations of existing rooms, such as a children’s bedroom by Vilmos Huszár from 1920 and a doctor’s clinic by Gerrit Rietveld from 1922, demonstrating a process of re-forming the past on the way to ideal De Stijl architecture.

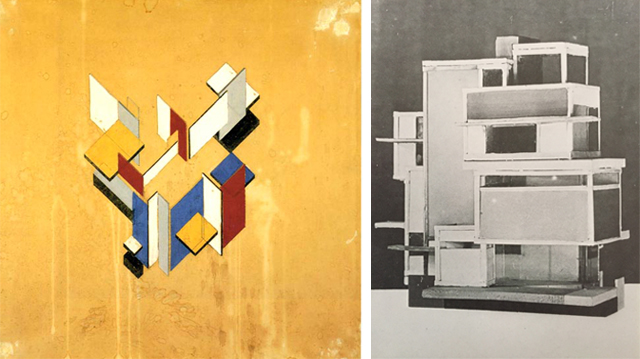

The formal debut of De Stijl architecture took place in 1923 under van Doesburg at Léonce Rosenberg’s Galerie L’ Effo rt Mode rne in Paris. This exhibition, Les Architectes du Groupe “de Styl,” displayed drawings, photographs, and models by van Doesburg, Cornelis van Eesteren, Vilmos Huszár, Willem van Leusden, J.J.P.Oud, Gerrit Rietveld, Jan Wils, and (surprisingly) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who contributed a photograph of his 1922 Glass Skyscraper model. This grouping of De Stijl architects (which at this time also included the Russian artist-architect El Lissitzky) indicates the expansive assembly of international members for the movement. Two projects attracting great attention from critics and later widely disseminated through publications and other exhibitions were the Maison d’Artiste (Artist’s House) and the Maison Particulière (Private House). Both were developed by van Doesburg in collaboration with van Eesteren (1897–1988) specifically for the Paris exhibition.

The Maison d’Artiste and the Maison Particulière, to be built of “iron and glass” and “concrete and glass,” respectively, provided literal and figurative models for future construction. As siteless, dynamic, spatial objects, each contains asymmetrical volumes rotated about central voids, projecting primary-colored planes as floors, walls, and ceilings into surrounding space. Van Doesburg constructed a model of the Maison d’Artiste and photographed it from below as an object suspended in space to display its ability to confront space and time and to expose its “sixth facade.”

Van Doesburg prepared axonometric “counter-construction” drawings for the Maison Particulière. These drawings emphasize the oblique relationships between pure planes and convey the abstract qualities of infinite extension without grounding them to a fixed vanishing point as in perspective. These axonometric constructions sought to liberate space and surface from earthly associations, or, as van Doesburg wrote in point 10 of his manifesto “Towards Plastic Architecture,” “This aspect, so to speak, challenges the force of gravity in nature.”

The furniture maker and architect Gerrit Rietveld (1888–1964), an early De Stijl participant who contributed a jewelry store design and assisted as a model builder for the Paris exhibition, produced the most significant work of De Stijl architecture, the Schröder House in Utrecht, completed in 1924.

Rietveld’s Red Blue Chair, initially produced without color in 1918, successfully mediated the transfer of De Stijl principles from painting to architecture. This seemingly simple wood chair, painted in the primary colors plus black in 1922 or 1923, is simultaneously articulated and synthetic and allows space to flow through it uninterrupted.

It, as well as the 1923 Maison Projects, inspired the De Stijl principles demonstrated in the Schröder House. This tiny two-story structure provides rich flexibility in its contrasting relations of elements and sliding partitions, allowing for closed or open living arrangements. As a house of options, or a cabinet to live in, it functions pragmatically and abstractly, attached to a series of row houses and opened wide to the surrounding environment. Although constructed primarily with traditional timber frame and brick in-fill, it appears as an a-material, innovative, anti-box in its exterior photographed images and its projecting pinwheel plan. Its innovatively detailed connections and built-in furnishings emphasized the house as a total work of art.

Rietveld drifted away from his associations with van Doesburg and De Stijl after the Schröder House but continued a long career building throughout the Netherlands by developing architectural relationships from De Stijl.

J.J.P.Oud (1890–1963), an urban architect practicing in Rotterdam, published essays and projects in the periodical De Stijl but held a tenuous relationship to De Stijl and van Doesburg after 1921. Van Doesburg collaborated with Oud on several residential projects, adding stained glass and painted color patterns to Oud’s architecture. Oud was simultaneously a pragmatist and an experimenter, as evident in his Wright-inspired Purmerend Factory project from 1919, a large industrial con crete volume nestled into an office area with a complex shallow-space facade.

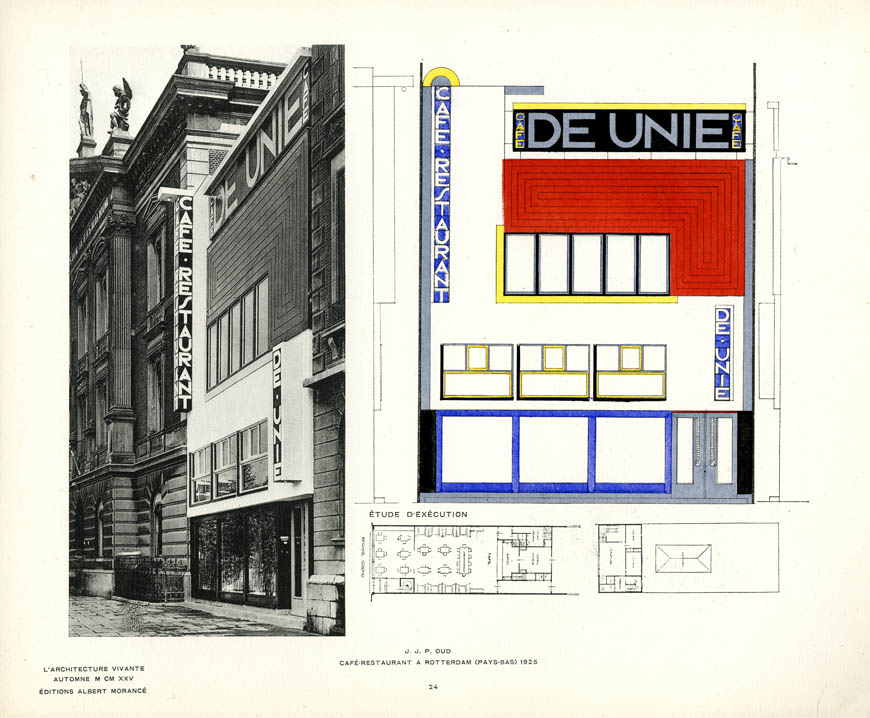

As a socially minded architect for the city of Rotterdam, he designed several expedient public housing projects there. His Spangen Housing (1919–21) and Tusschendijken Housing (1921–24), both displayed in the 1923 De Stijl exhibition, achieved efficiency and economy through standardization and use of brick as an everyday exterior material while including horizontal-vertical articulations of corner elements related to spatial De Stijl ideas. His Kiefhoek Housing (1925–29) contained a-material primary-color elements as a type of De Stijl village. His temporary Superintendent’s Office (1923) for Oud-Mathenesse Housing was a De Stijl folly in primary colors and cubic forms, derived from the paintings of Mondrian and van Doesburg. Oud’s Cafe de Unie, built in Rotterdam in 1925, was bombed during World War II and reproduced at another location in the city in 1986, signifying its architectural stature conveyed through publications. Its facade, a billboard manifesto advertising De Stijl, displays a low-relief composition of primary colors with integrated signage.

After 1924, van Doesburg and Mondrian clashed over appropriation of the diagonal into the rectilinear compositions characteristic of De Stijl painting. Mondrian developed his diamond compositions, rotating the frames of his paintings 45 degrees while retaining the horizontal-vertical relationships of the rectilinear elements themselves to emphasize extension of the boundaries of the artwork beyond the inconsequential oblique frame. Van Doesburg, on the other hand, began at this time to invert Mondrian’s strategy, employing diagonal relationships of lines and planes within an orthogonal frame.

Influenced by these interrelated yet oppositional developments, van Doesburg reified their spatial implications in two rooms of the Cafe Aubette (dawn), constructed within an 18th-century building in Strassbourg, France, between 1926 and 1928. The complex commission was carried out in conjunction with Hans Arp and Sophie Täuber Arp, who designed other rooms. This ultimate fusion of art and life using De Stijl ideas in combination with off-the-shelf materials, furniture, and lighting fixtures resulted in an ideal De Stijl forum. By re-forming the spaces of this nightclub with striking manifestations of line and color in relation to the bodily activity of dancing and the projection of cinema, van Doesburg temporarily accomplished De Stijl synthesis through unity from the tension of opposites. The Small Dance Hall’s primary-color panels on the walls and ceiling align orthographically with the rectilinear room, resulting in a clear fusion of surface and space. Enacting van Doesburg’s transition into “elementarism” and influenced by the oblique “counter-construction” drawings from the Maison Particulière, his Cinema-Dance Hall features diagonal color patterns extending through the room’s corners to dismantle the confines of the space. In the Cafe Aubette, reconstructed in 1995, the projection of cinema and the gestures of bodies in motion establish a kinetic dialogue between art and life. Synthesizing architecture, painting, sculpture, and applied arts as Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art, van Doesburg created the ultimate De Stijl space and representation of modernism: a dialectically constructed avant-garde cafe-salon interiorized as spatial art rather than occupying rooms with art hung on the walls.

Van Doesburg built a simple house for himself and his wife, Nelly, in Meudon-Val Fleury, outside of Paris, between 1927 and 1930. Succumbing to tuberculosis, he died in a sanatorium in Davos, Switzerland, in 1931. De Stijl as an avant-garde movement unfortunately expired with van Doesburg. Subsequent developments of modernist and contemporary architecture have been crucially reliant on the spatial conceptions of the De Stijl architects, from the works of Le Corbusier and Marcel Breuer to Peter Eisenman, John Hejduk, and MVRDV. De Stijl architecture engaged space and surface in a simultaneously elemental and universal manner, proposing meaning and spirituality within abstraction and “pure” relations of forms.

MARK STANKARD

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.1 (A-F). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2004. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1915, the Villa Henny, Huis ter Heide, NETHERLANDS, Robert van’t Hoff |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1917, Red Blue Chair, Gerrit Rietveld |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1920, Design for Chair, Piet Zwort and Vilmos Huszar |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

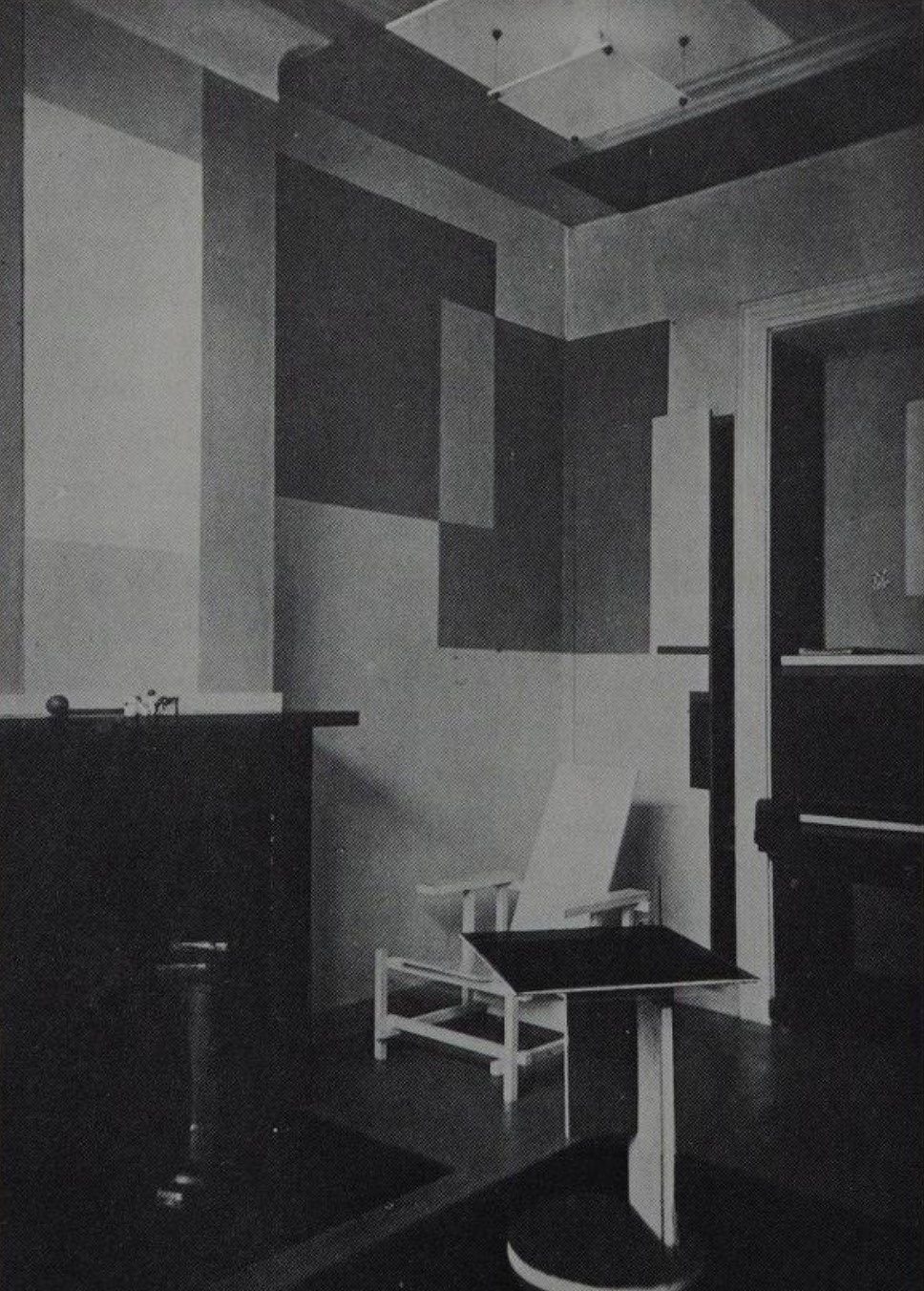

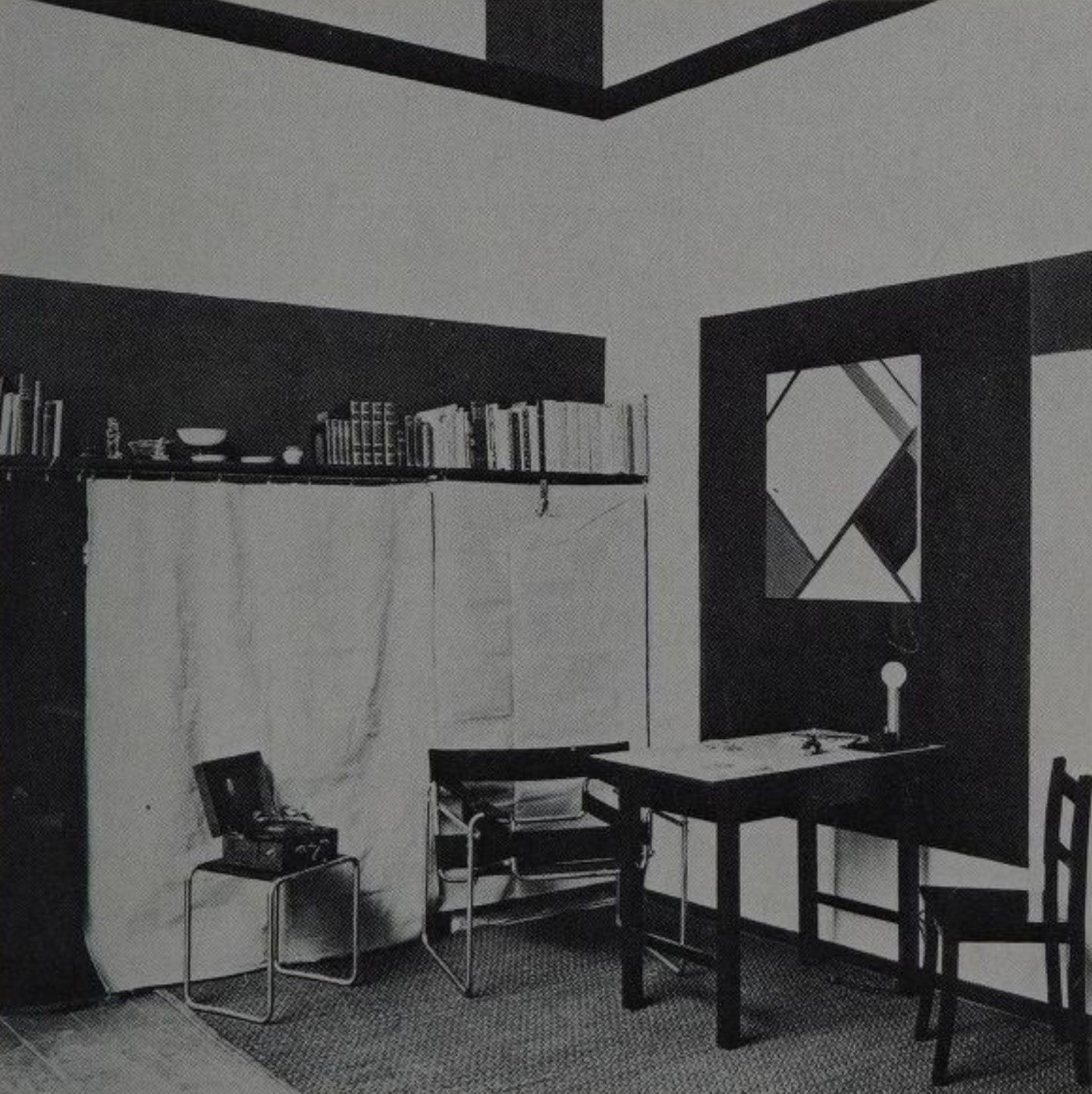

1920-1921, Atelier Berssenbrugge, The Hague, NETHERLANDS, Vilmos Huszar |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1922, Color, function of architecture,

Theo van Doesburg |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Color Design for Amsterdam University Hall, Theo van Doesburg |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Proun Space, reconsiruction, El Lissitzky, Stedelik,

Von Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, NETHERLANDS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Maison d’Artiste, Theo van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren’s |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1923, Maison Particuliére, Theo van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren’s |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1924, Piet Mondrian in his studio, Paris, FRANCE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1924, Spatial Color Composition in Gray, Brugman House, The Hogue,

NETHERLANDS, Vilmos Huszar |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1924, Schröder House, Utrecht, NETHERLANDS, Gerrit Rietveld |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

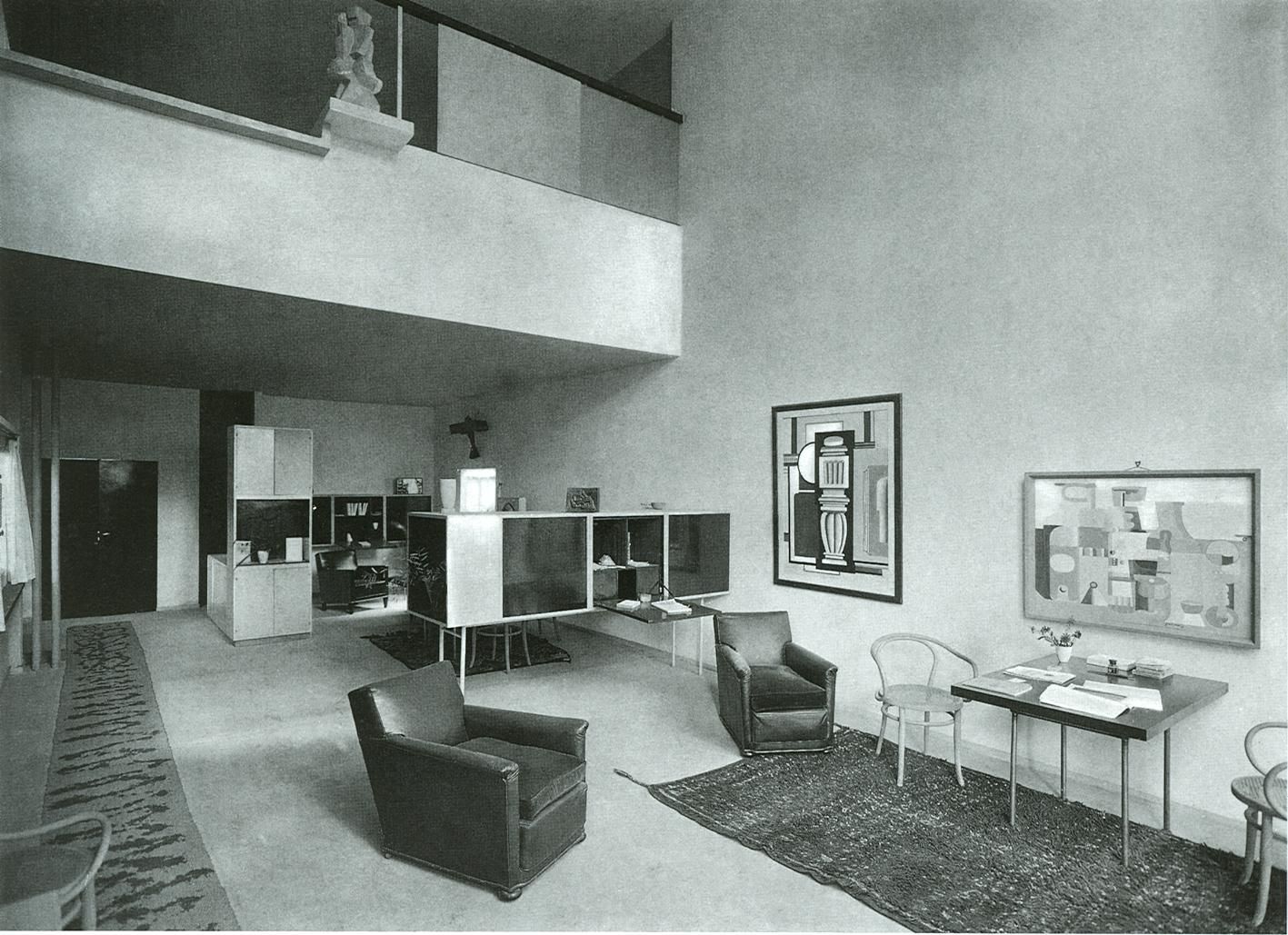

1925, Pavilion of the New Spirit, Paris, FRANCE, Le Corbusier |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925, Cafe de Unie, Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, J.J.P.Oud |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925, Cafe de Unie, Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, J.J.P.Oud |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1926, Piet Mondrian's studio, Paris, FRANCE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1925-1929, Kiefhoek Housing, Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, J.J.P.Oud |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1926-1928, the Cafe Aubette, Strassbourg, FRANCE, Theo van Doesburg |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1926-1928, the Cafe Aubette, Strassbourg, FRANCE, Theo van Doesburg |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927, Domela Apartment, Berlin, GERMANY, Cesar Domela |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1927-1930, van Doesburg's house, Nelly, in Meudon-Val Fleury, FRANCE, Theo van Doesburg |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

LISSITZKY, EL

OUD, J.J.P.

RIETVELD, GERRIT THOMAS

VAN DOESBURG, THEO

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

BUILDINGS

1915, the Villa Henny, Huis ter Heide, the Netherlands, Robert van’t Hoff

1919-1921, Spangen Housing, Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, J.J.P.Oud

1921-1924, Tusschendijken Housing , Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, J.J.P.Oud

1923, Maison d’Artiste, Theo van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren’s

1923, Maison Particuliére, Theo van Doesburg and Cornelis van Eesteren’s

1924, Schröder House, Utrecht, the Netherlands, Gerrit Rietveld

1925, Cafe de Unie, Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, J.J.P.Oud

1925-1929, Kiefhoek Housing , Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, J.J.P.Oud

1926-1928, the Cafe Aubette, Strassbourg, France, Theo van Doesburg

1927-1930, van Doesburg's house, Nelly, in Meudon-Val Fleury, FRANCE, Theo van Doesburg

FURNITURE

1917, Red Blue Chair,Gerrit Rietveld |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

INTERNAL LINKS

Lissitzky, El; Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig ; Oud, J.J.P. ; Rietveld, Gerrit ; van Doesburg, Theo

FURTHER READING

Writings on De Stijl seldom focus specifically on architecture, typically integrating multiple aspects of De Stijl. Many more books and articles on De Stijl, Piet Mondrian, Theo van Doesburg, Gerrit Rietveld, J.J. P.Oud, Vilmos Huszar, and other De Stijl participants, from the time period itself to the present, are available in several languages.

Barr, Alfred H., Jr., De Stijl 1917–1928, New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1952

Blotkamp, Carel, et al., editors, De Stijl, the Formative Years, translated by Charlotte I.Loeb and Arthur L.Loeb, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1986

Boekraad, Cees, Flip Bool, and Herbert Henkels, editors, De Nieuwe beelding in de architectuur; Neo Plasticism in Architecture: De Stijl, Delft: Delft University Press, and Den Haag: Haags Gemeentemuseum, 1983

Bois, Yve-Alain, “The De Stijl Idea,” Art in America 70, no. 10 (November 1992)

De Stijl 1 and De Stijl 2 (Amsterdam: Athenaeum, 1968). Reprint of the periodical De Stijl, edited by Van Doesburg, from 1917–1929, and 1932.

Friedman, Mildred, editor, De Stijl 1917–1931: Visions of Utopia, Minneapolis, Minnesota: Walker Art Center, and New York: Abbeville Press, 1982

Jaffé, Hans Ludwig C, De Stijl, 1917–1931; the Dutch Contribution to Modern Art, Amsterdam: Meulenhoff, and London: Tiranti, 1956

Michelson, Annette, “De Stijl, Its Other Face: Abstraction and Cacaphony, or What Was the Matter with Hegel?” October 22 (Autumn 1982)

Mondrian, Piet, The New Art—The New Life: The Collected Writings of Piet Mondrian, edited and translated by Harry Holtzman and Martin S.James, Boston: G.K.Hall, 1986

Troy, Nancy J., The De Stijl Environment, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1983

De Stijl: 1917-1931: Visions of Utopia

De Stijl (World of Art)

Towards Universality: Le Corbusier, Mies and De Stijl

De Stijl, 1917-1928: the Museum of Modern Art Bulletin (The Museum of Modern Art bulletin)

De Stijl, 1917-1931: The Dutch Contribution to Modern Art

"Stijl, De" |

| |

|

|