| ALL |

|

MUSEUM

| OVERVIEW |

|

| |

The ancient rites of giving sanctuary to the muse while bringing the muse to the people are the dual intentions of the museum. In the 20th century, these rites increasingly call forth the muses of both art and architecture. Because a museum as architecture is also judged as a work of art, a tremendous cultural and aesthetic burden falls on the designer of a museum, for the building is surely to be the largest acquisition that any art museum is likely to make, and therefore the structure becomes a major accession to the museum’s collection. Thus, through the typology of the museum, bricks, and stones and steel come to connoisseurship.

Because they encompass so much artistic aspiration, museums are important aesthetic touchstones, and those of the 20th century will become significant points of reference for future interpretation of the aesthetics of our era. Today, we have come to expect modern landmarks in museum design and complex building programs defining each new decade. Major European and American cities, from Paris to Los Angeles, have demonstrated their artistic commitment through museum construction, but smaller places as well, such as Nimes, Bilbao, Milwaukee, and Denver, have invested in important buildings, to the surprise and admiration of the rest of the world. In the 20th-century explosion of museum design, architects have explored myriad manifestations of the modern, ranging from the formalized, classical geometry of Mies van der Rohe’s Altes Museum (Berlin) through the vaulted light and space of Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum (Fort Worth, Texas) to the curvilinear expressionism of the two Guggenheims, Frank Lloyd Wright's (New York City) and Frank Gehry’s (Bilbao, Spain). Museum architecture of the late 20th century has taken many forms programmatically as well: the creation of wholly new edifices, such as Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum of American Art (New York City); agglomerative ensembles of existing museum buildings, as in Gwathmey Siegel's Harvard University Art Museums; contemporary additions to historic museums, such as Roche Dinkeloo’s Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) and Robert Venturi’s Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery (London); and adaptations of non-museum architecture to museum space, as at the Musee Picasso (Paris) and the Tate Gallery (London) by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron of Switzerland.

Museums must strike a subtle balance: to be stunning sites and spaces in their own right and yet to be friends to art. Works of art in themselves, they must be true to their stated mission, which is to show other art to its best advantage. Tour-de-force architectural form must not forget artistic function, and for the museum, this means to show paintings and sculpture advantageously within an inviting public arena. This is the singular challenge of museum architecture, for as always, architecture is found to be the only art form to bear the burden of function and necessity. A small selection of truly exceptional masterpieces of modern museum architecture whose quality is based on design creativity, significance or influence of design, and appropriateness of architecture to art will underscore the significance of this building type in the 20th century. Therefore, the designs chosen are those that likely will become models defining modern museum architecture rather than the most site-specific or idiosyncratic works. Selected works are ones that demonstrate aesthetic insight, that are complementary to art, and that together begin to define the typology of the 20th-century museum. These works of late modernism will serve to explain the relationship among art, architecture, and viewer in the future, as earlier buildings, such as Le Corbusier’s Pavillon de l’esprit nouveau (1925) and Mies’s German Pavilion (1929) for the Barcelona Exhibition, have defined exhibition architecture in the past. Some exemplars of 20th-century museum architecture that one can study are the Museum of Modern Art (1939) in New York, the East Building of the National Gallery (1978) in Washington, D.C., and the J. Paul Getty Museum (1997) in Los Angeles.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York City (MoMA) is the cornerstone of modern museum architecture, for it is both concretely and symbolically representative of the meaning of the modern museum. Founded in 1929, MoMA advanced the first modern architecture exhibitions in the United States as well as the first architecture and design collections and curators. Even the architectural term “International Style,” in its American incarnation, was coined there by the 1932 exhibition of the same name.

The original 1939 building by Philip L. Goodwin and Edward Durell Stone, a sleek, highly polished, streamlined envelope for art within an urban setting, was well ahead of its time stylistically for America of the 1930s. Programmatically, too, MoMA was shaping the future of museum design, for now museum architecture would accommodate the hanging and viewing of works, ranging from the easel-size canvases of Cezanne to the wall-size ones of Pollock. The typology of the modern museum, in contradiction to the weighty buildings of the Beaux-Arts, was, after MoMA, to be conceived of as a lightweight, permeable, volumetric enclosure of architecture about works of art. MoMA is currently undergoing a 21st-century expansion, a project designed by the Tokyo architect Yoshio Taniguchi (begun in 1997 with a completion date of 2005). With the many iterations of its architecture in the last decades of the 20th century, MoMA seems to be constantly in flux, although perhaps this state is fitting for the meaning of modernism. The passage of light and views from within to without at MoMA is seamless. In a great contribution to the history of museum design, the galleries are well designed for the uninterrupted contemplation of the works, whereas the public spaces are designed to orient the viewer to the urban world outside the museum's walls.

Early in the design history of MoMA, architect Philip Johnson there created one of the most sophisticated open spaces within any city: the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden, a mid-century urban space that is truly innovative and almost romantically modern, if such a thing is possible. Here, three-dimensional works by Picasso, Rodin, Matisse, and Henry Moore are played in counterpoint to nature, the sculpture dispersed among stands of weeping beech and still water, in a Zen-like composition. Basically unchanged since its inception in 1953, this space is a sanctuary for modernism, where quiet contemplation of art and nature is enclosed by walls of abutting skyscrapers and townhouses and enlivened by their urbane architectural presence. Here art, architecture, nature, and city intersect.

Another of the significant museum spaces in the United States that allows space, architecture, and city to interact with art is the East Building of the National Gallery (1978), Washington, D.C., by I.M. Pei. This geometric, sculptural composition in acute angles and white marble sets the standard to which American public architecture should aspire. In a complex program that simultaneously must exhibit art, create public spaces, respond to its context (which includes the U.S. Capitol and Pennsylvania Avenue), and create a visual landmark on the National Mall, the architect has more than succeeded. Pei has gone further, designing a building that both shows

art to its advantage via visually varied galleries in breathtaking interior spaces filled with the sunlight of the south and goes on to create an exterior design so elegant as to become an architectural landmark and a work of art in itself. Pei’s highly creative solution is based on geometry, concretely and metaphorically. He has used the triangle, the trapezoid, the tetrahedron, and the acute angle of L’Enfant’s Washington plan to dictate his plan. Within this geometric context, the complex interior glassed spaces and the contrasting smooth white marble exterior elevations together create compositional integrity.

The American National Gallery foreshadowed Pei’s work for another national gallery, the French Louvre (1989). Here, again challenging program for a structure symbolic of a nation’s artistic heritage, the architect found a solution based on geometry. Faced not only with the long historical memory of France but also with a massive site along the Seine River, including an elongated palace and enclosed courtyards, Pei wisely did not try to imitate the Louvre of history. Instead, in a multi-layered juxtaposition, he designed a boldly modern glass pyramidal structure that responds to the ancient buildings. Pei’s pyramid seems to comment on the French love of exoticism in art, on Napoleonic history, and on the Egyptian collections of the Louvre. As the geometry of the pyramid is to the Louvre, the geometry of the isosceles triangle is to the National Gallery. Because geometry in architecture is eternal, Pei’s pyramid and his triangle speak equally to modernism and to the antique.

The continuity of antiquity with modernism has also been explored thematically by Richard Meier in the J. Paul Getty Museum (1997) in Los Angeles. In a number of ways, this monumental project is the summation of museum architecture—even architecture in general—of the late 20th century, a kind of fin-de-siècle statement of an era. Opening with the close of the millennium and having been under construction during one of the most devastating earthquakes to hit an American city—and surviving—the Getty is a triumph of the spirit of modern architecture. Sited atop a seismically active city, it represents almost a challenge to the gods. We recall that the predecessor to Meier's Getty, the Getty Villa (1980, under renovation) in Malibu, California, is a replica of a villa in Herculaneum (and we need no reminder of the fate of that place). Perhaps it is hubris to bring art to Olympus, but this is exactly what the monumental Getty has done.

The giant edifice, floating white above the city and the Pacific, is a metaphor for the history of modern architecture and ideology. The building is rich with architectural references waiting to be read. The most apparent reference is to the Le Corbusian white machine in the garden, but the building also recalls the Bauhaus “crystalline cathedral of the arts” imagery as well as the futurist manifesto. More contemporary references are to Louis Kahn’s Salk Institute and Kimball Art Museum and less directly to Wright’s spiraling Guggenheim.

As a silent white train pulls the viewer up the mountain through fragrant chaparral, the city of today—its freeways and its smog—falls away below. The viewer begins to feel a strong sense of ascent to the promontory, a latter-day Athenian processional to the Acropolis. At the hilltop, the visitor must leave the white train and climb higher, via symbolic marble steps, toward the modern temple to art. Now at last, one views Meier's Getty in full, the sleek, machined, semi-circular, arcing monumental entrance, leading into a dramatically void space of sun and sculpted waterways. Configured like a Mediterranean village, the limestone-faced pavilions housing the art are dispersed axially about, and cling to, the sunlit central courtyard. Although on first sight it is completely Mediterranean white, the materials—enamelled metal squares and cubic cur travertine—are subtly varied and change color and contrast with the setting sun. In a subtle touch, the architect has exposed rough-cut limestone honeycombed with primitive fossils. Thus, from the most primitive geologic sources in nature—through the finely cut, unmortgaged stone of the ancients to the machined metals of the moderns—the materials of the museum symbolically re-create the history of art.

Leslie HUMM CORMIER

Sennott R.S. Encyclopedia of twentieth century architecture, Vol.2 (G-O). Fitzroy Dearborn., 2005. |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| GALLERY |

|

| |

|

| |

1955, Museum of Modern Western Art, Tokyo, JAPAN, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1957, Ahmedabad Museum, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1959, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA, Frank Lloyd Wright |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1956-1964, Museo di Ca Carlo Scarpa Carlo Scarpastelvecchio, Verona, ITALY, Carlo Scarpa |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1966, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, USA, Louis Kahn |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1964-1966, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, USA, MARCEL BREUER |

| |

|

| |

, Zurich, Switzerland, LE CORBUSIER.jpeg) |

| |

1967, Exhibition hall (Heidi Weber Museum), Zurich, Switzerland, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1967-1979, North wing of the Metropolitan museum, New York, USA, Kevin Roche |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1968, Altes Museum, Berlin, GERMANY, Mies van der Rohe |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1969-1976, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

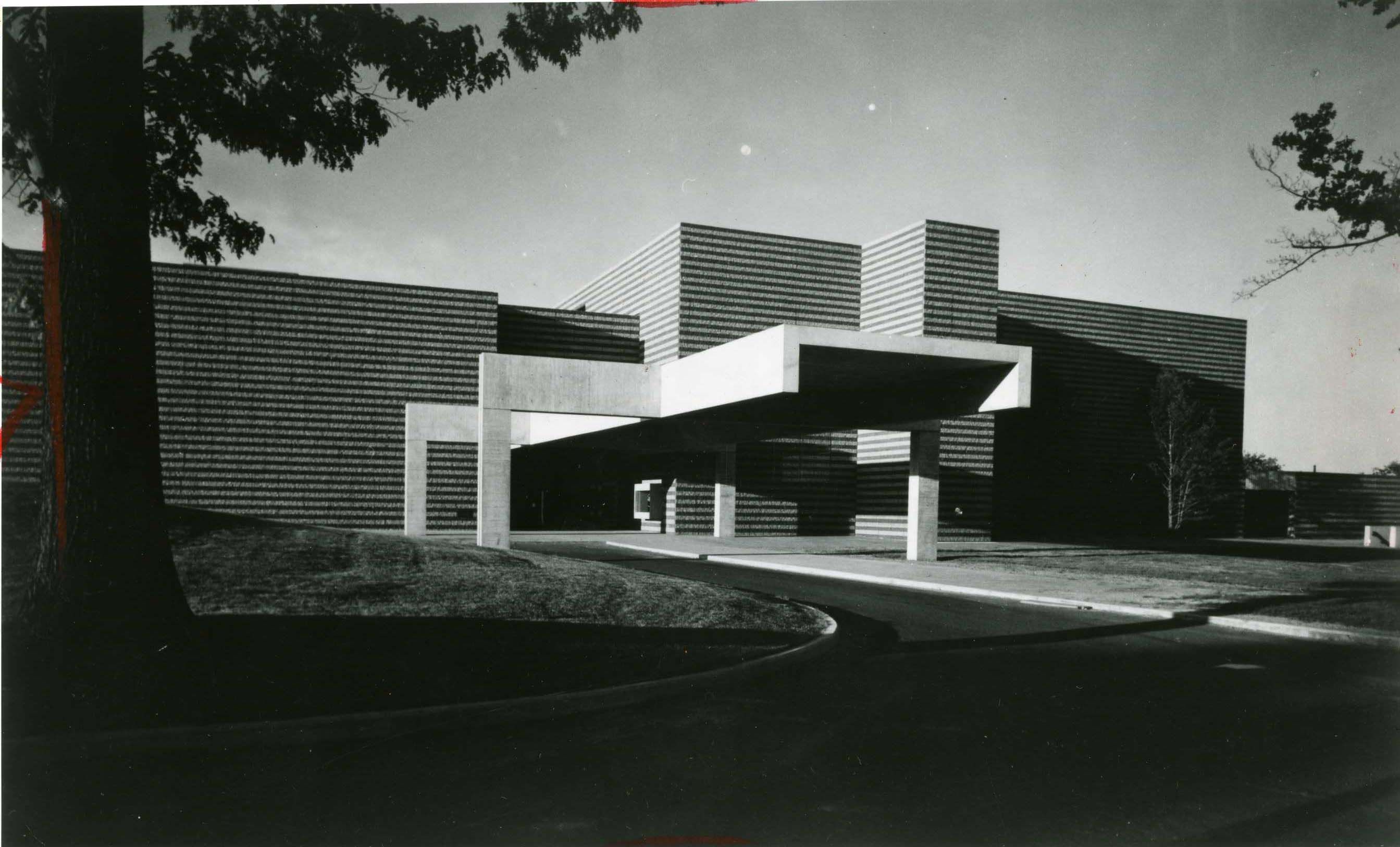

1971, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, USA, MARCEL BREUER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1971-1977, CENTRE GEORGES POMPIDOU, PARIS, FRANCE, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1972-1983, The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, UK, Barry Gasson |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1974, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C., USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1977-1984, The Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart, GERMANY, James Stirling |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1978, the East Building of the National Gallery, Washington, D.C., USA, LM. Pei |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1978-1991, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, UK, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1980-1983, The High Museum of Art, Atlanta, USA, Renzo Piano |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

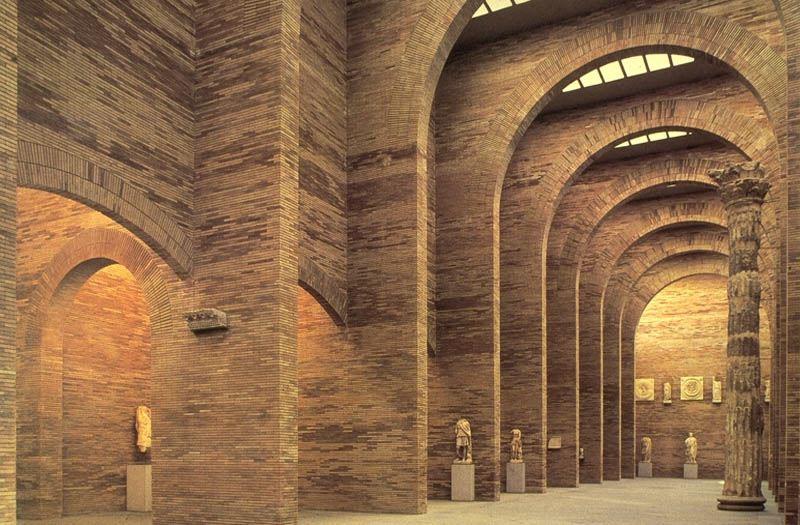

1980-1985, National Museum of Roman Art, Merida, SPAIN, Rafael Moneo |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1982, Städtisches Museum, Abteiberg, GERMANY, Hans Hollein |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1982-1986, THE MENIL COLLECTION, HOUSTON, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

, Paris, FRANCE, I.M. PEI.jpeg) |

| |

1983–1989, Le Grand Louvre (expansion, Phase I), Paris, FRANCE, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1984-1997, The Getty Center, Los Angeles, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1987-1992, Kunsthal, Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

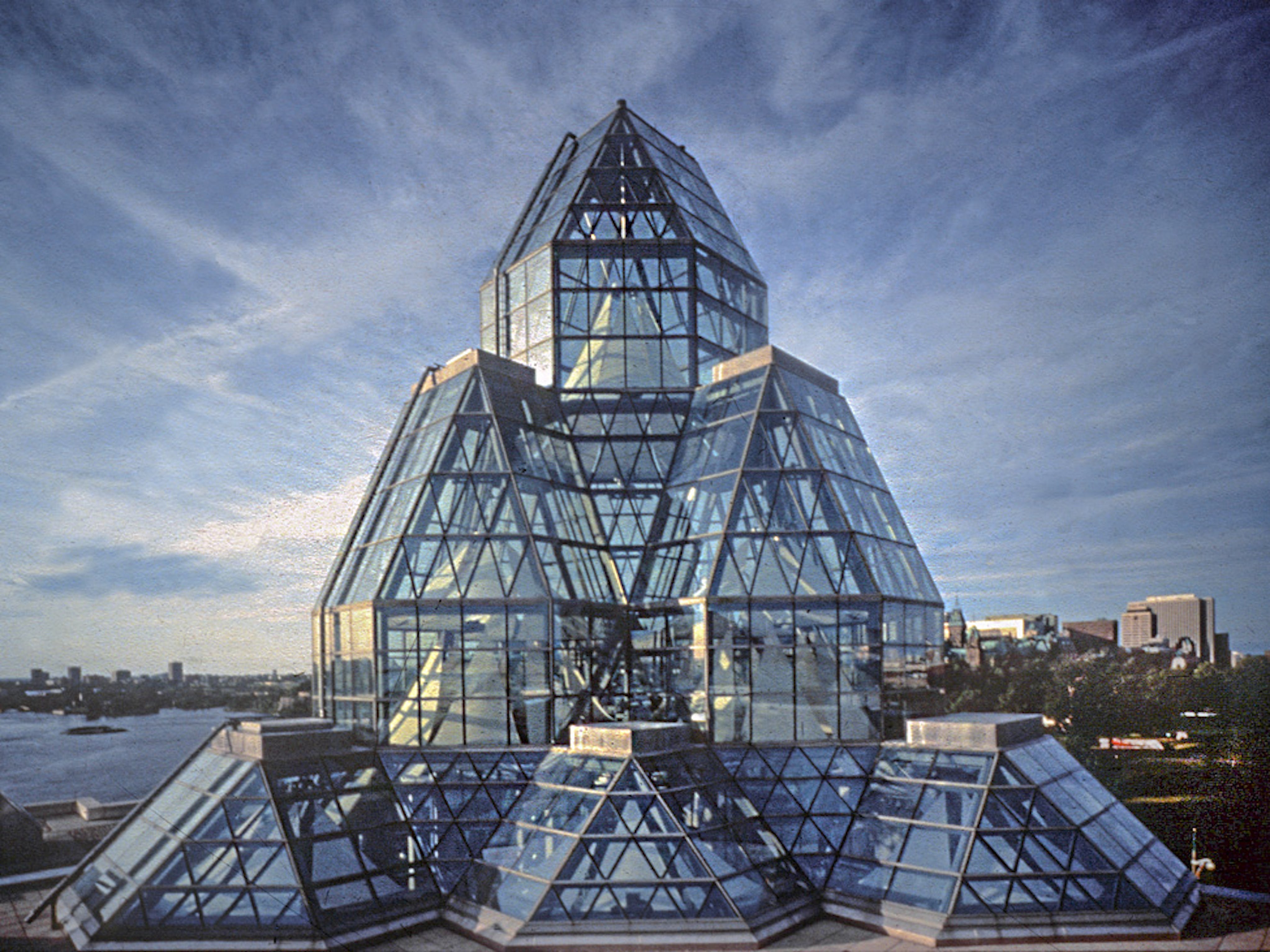

1988, National Gallery, Ottawa, CANADA, MOSHE SAFDIE |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1989-1995, MOMA museum of modern art, San Francisco, USA, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

, RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL, OSCAR NIEMEYER.jpeg) |

| |

1996, Museum of Contemporary Art (Museu de Arte Contemporánea), RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL, OSCAR NIEMEYER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1996-2004, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, South Korea, JEAN NOUVEL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1997, Guggenheim, Bilbao, SPAIN, Frank Gehry |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1997, Red Dot Design Museum, Essen, Germany, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

, New York, USA, Yoshio Taniguchi,.jpg) |

| |

1997-2004, The Museum of Modern Art, (MoMA), New York, USA, Yoshio Taniguchi |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

1999–2018, James-Simon-Galerie, Museum Island, Berlin, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2000-2009, CHICAGO ART INSTITUTE – THE MODERN WING, CHICAGO, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2001-2005, Ordrupgaard Museum, Copenhagen, DENMARK, ZAHA M. HADID |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2002-2005, De Young Museum,

San Francisco, USA, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2003, Zinc-Mine Museum, Almannajuvet, Sauda, Norway, PETER ZUMTHOR |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2003-2019, The National Museum of Qatar, Doha, Qatar, JEAN NOUVEL |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2005, Tate Modern, London, UK, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2005–2013, Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri, USA, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2007-2011, Steilneset, Memorial to the Victims of the Witch Trials,Vardo, Norway, PETER ZUMTHOR |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2008-2018, Fondazione Prada, Milan, ITALY, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2012, Louvre-Lens, Lens, France, KAZUYO SEJIMA |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2015, GES 2, MOSCOW, RUSSIA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2016-2021, MKM Museum Küppersmühle, Extension, Duisburg, Germany, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

2019, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, USA, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| ARCHITECTS |

|

| |

BOTTA, MARIO

CHIPPERFIELD, DAVID

HERZOG & DE MEURON

HOLLEIN, HANS

KAHN, LOUIS I.

KOOLHAAS, REM

MEIER, RICHARD

MIES VAN DER ROHE, LUDWIG

PEI, I.M.

PIANO, RENZO

TANGE, KENZO |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| BUILDINGS |

|

| |

1955, Museum of Modern Western Art, Tokyo, JAPAN, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1957, Ahmedabad Museum, Ahmedabad, India, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1959, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, USA, FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT |

| |

|

| |

1962, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, New York, USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

1966-1972, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

1964-1966, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, USA, MARCEL BREUER |

| |

|

| |

1967, Exhibition hall (Heidi Weber Museum), Zurich, Switzerland, LE CORBUSIER |

| |

|

| |

1967-1979, North wing of the Metropolitan museum, New York, USA, Kevin Roche |

| |

|

| |

1968, Altes Museum, Berlin, GERMANY, Mies van der Rohe |

| |

|

| |

1968, Everson Museum of Art, Syracuse, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

1969-1976, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, USA, LOUIS I. KAHN |

| |

|

| |

1971, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, USA, MARCEL BREUER |

| |

|

| |

1971-1977, CENTRE GEORGES POMPIDOU, PARIS, FRANCE, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

1973, Herbert F.Johnson Museum of Art,

Cornell University, Ithaca, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

1974, Minneapolis Arts Complex, Minneapolis, USA, KENZO TANGE |

| |

|

| |

1974, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Houston, USA, MIES VAN DER ROHE |

| |

|

| |

1974, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden,

Washington, D.C., USA, SKIDMORE, OWINGS AND MERRILL |

| |

|

| |

1976-1979, Bauhaus Archiv-Museum, BERLIN, GERMANY, WALTER GROPIUS |

| |

|

| |

1978, Iwasaki Art Museum, Ibusuki, Kagoshima, JAPAN, FUMIHIKO MAKI |

| |

|

| |

1978, National Gallery of Art, East Building,

Washington, USA, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

1978-1991, Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich, UK, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

1979-1985, Museum for the Decorative Arts, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1980-1985, National Museum of Roman Art, Merida, SPAIN, Rafael Moneo |

| |

|

| |

1980-1983, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1982, ABTEIBERG MUNICIPAL MUSEUM, MÖNCHENGLADBACH, GERMANY, HANS HOLLEIN |

| |

|

| |

1982, Hyogo Prefecture Museum of History, Hyogo, JAPAN, KENZO TANGE |

| |

|

| |

1982-1984, Des Moines Art Center Addition, Des Moines, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1982-1986, THE MENIL COLLECTION, HOUSTON, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

1983–1989, Le Grand Louvre (expansion, Phase I),

Paris, FRANCE, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

1984-1997, The Getty Center, Los Angeles, USA, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1985-1990, Art gallery Watari-Um, Tokyo, Japan, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1986, National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, JAPAN, FUMIHIKO MAKI |

| |

|

| |

1986 - 1993, Ulm Stadhaus Exhibition & Assembly Building, Ulm, Germany, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1987-1992, Kunsthal, Rotterdam, NETHERLANDS, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

1988, National Gallery, Ottawa, CANADA, MOSHE SAFDIE |

| |

|

| |

1988-2002, MART museum of modern & contemporary art, Rovereto, Italy, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1989, Yokohama Art Museum, Kanagawa, JAPAN, KENZO TANGE |

| |

|

| |

1989-1995, MOMA museum of modern art, San Francisco, USA, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1989-1997, River and Rowing Museum, Henley-on-Thames, UK, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

1991, Sackler Galleries, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

1991-1997, BEYELER FOUNDATION MUSEUM, RIEHEN, SWITZERLAND, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

1993, Carré d'Art, Nîmes, France, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

1993–2009, Neues Museum, Museum Island, Berlin, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

1993-1996, Museum Jean Tinguely, Basel, Switzerland, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1994, Addition to Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

1995-2006, Ara Pacis Museum, Rome, Italy, RICHARD MEIER |

| |

|

| |

1996, Museum of Contemporary Art (Museu de Arte Contemporánea), RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL, OSCAR NIEMEYER |

| |

|

| |

1996-2004, Leeum, Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, South Korea, JEAN NOUVEL |

| |

|

| |

1997, Guggenheim, Bilbao, SPAIN, Frank Gehry |

| |

|

| |

1997, Red Dot Design Museum, Essen, Germany, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

1998, Nice Asian Art Museum, Nice, France, KENZO TANGE |

| |

|

| |

1998, Miho Museum, Kyoto, JAPAN, I.M. PEI |

| |

|

| |

1998-2003, Bodmer Foundation, Geneva, SWITZERLAND, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

1999-2003, NASHER SCULPTURE CENTER, DALLAS, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

1999-2005, HIGH MUSEUM EXPANSION, ATLANTA, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

1999-2005, ZENTRUM PAUL KLEE, Berne, Switzerland, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

1999–2018, James-Simon-Galerie, Museum Island, Berlin, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2000-2009, The Bechtler Museum of Modern Art, Charlotte, USA, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

2000-2009, CHICAGO ART INSTITUTE – THE MODERN WING, CHICAGO, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2000–2015, MUDEC Museum (Museo delle Culture di Milano), Milan, Italy, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2001, JEWISH MUSEUM BERLIN, Berlin, Germany, DANIEL LIBESKIND |

| |

|

| |

2001–2006, Museum of Modern Literature, Marbach am Neckar, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2001-2005, Ordrupgaard Museum, Copenhagen, DENMARK, ZAHA M. HADID |

| |

|

| |

2002-2004, Leeum Museum, Seou, KOREA, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

2002-2005, De Young Museum,

San Francisco, USA, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

2002-2013, MUSE MUSEO DELLE SCIENZE, TRENTO, ITALY, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2003, Zinc-Mine Museum, Almannajuvet, Sauda, Norway, PETER ZUMTHOR |

| |

|

| |

2002-2016, Tsinghua Art Museum, Tsinghua University, Beijing, P.R. China, MARIO BOTTA |

| |

|

| |

2003–2007, Liangzhu Museum, Hangzhou, China, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2003-2008, BROAD CONTEMPORARY ART MUSEUM, LOS ANGELES, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2003-2019, The National Museum of Qatar, Doha, Qatar, JEAN NOUVEL |

| |

|

| |

2005, Tate Modern, London, UK, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

2005-2012, RENOVATION AND EXPANSION OF THE ISABELLA STEWART GARDNER MUSEUM, BOSTON , USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2005–2013, Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri, USA, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2006, Washington University in St. Louis Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts, Missouri, USA, FUMIHIKO MAKI |

| |

|

| |

2006–2011, Turner Contemporary, Margate, UK, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2006-2012, ASTRUP FEARNLEY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, OSLO, NORWAY, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2006-2014, HARVARD ART MUSEUMS RENOVATION AND EXPANSION, CAMBRIDGE, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2007–2009, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2007-2011, Steilneset, Memorial to the Victims of the Witch Trials,Vardo, Norway, PETER ZUMTHOR |

| |

|

| |

2007-2013, KIMBELL ART MUSEUM EXPANSION, FORT WORTH, USA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2008-2016, STAVROS NIARCHOS FOUNDATION CULTURAL CENTER, ATHENS, GREECE, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2008-2018, Fondazione Prada, Milan, ITALY, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

2008–2018, Royal Academy of Arts masterplan, London, UK, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2009–2013, Museo Jumex, Mexico City, Mexico, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2010, New Museum, New York, USA, KAZUYO SEJIMA |

| |

|

| |

2010, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

2010-2013, Pérez Art Museum Miami, Miami, USA, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

2011-2015, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art , Moscow, RUSSIA, REM KOOLHAAS |

| |

|

| |

2012, Louvre-Lens, Lens, France, KAZUYO SEJIMA |

| |

|

| |

2013–2019, West Bund Museum, Shanghai, China, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2014, Aga Khan Museum, Ontario, Canada, FUMIHIKO MAKI |

| |

|

| |

2014–2018, Zhejiang Museum of Natural History, Anji, China, DAVID CHIPPERFIELD |

| |

|

| |

2015, GES 2, MOSCOW, RUSSIA, RENZO PIANO |

| |

|

| |

2016, Sumida Hokusai Museum, Tokyo, Japan, KAZUYO SEJIMA |

| |

|

| |

2016-2021, MKM Museum Küppersmühle, Extension, Duisburg, Germany, HERZOG & DE MEURON |

| |

|

| |

2019, Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, USA, NORMAN FOSTER |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| MORE |

|

| |

FURTHER READING

Biasini, Emile, Jean Lebrat, Dominique Bezombeg, and Jean-Michel

Vincent, Le grand Louvre: Métamorphose d'un musée, 1981-1993,

Paris: Electa Moniteur, 1989; as The Grand Louvre: A Museum

Transfigured, 1981-1993, translated by Charlotte Ellis and

Murray Wyllie, Paris: Electa Moniteur, 1989

Mack, Gerhard Art museums into the 21st century, Birkhäuser, 1999

McLanathan, Richard (editor), East Building, National Gallery of Art:

A Profile, Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1978

Walsh, John, and Deborah Gribbon, The J. Paul Getty Museum and

ts Collections: A Museum for a New Century, Los Angeles: J. Paul

Getty Museum, 1997

The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 1960

East Building: National Gallery of Art : A Profile

Yoshio Taniguchi: Nine Museums

The Whitney Museum (Building Block) (Building Block S.)

Museums for a New Millennium: Concepts Projects Buildings |

| |

|

|